Archive

Happy Larry Summers isn’t the Fed Chair Day! #OWS

So yesterday there I was with my Occupy group, we’d just gone over our plans for the second anniversary of Occupy Wall Street this coming Tuesday. We talked over releasing our book and the press conference in Zuccotti Park at 10:15am. We talked over the group’s web presence and how we had to improve it a bit before then, what flyers to hand out with the book, and how to get everyone copies of the book before then. In other words, logistics.

Then we turned to the content of the meeting, namely working on our op-ed focused on Larry Summers and why he shouldn’t be named the Fed Chair.

We’d brainstormed about it last week, and I put together a crappy first draft, and then another in our group had blown away my milquetoast logical argument with a couple of paragraphs of pure Occupy outrage. We were thinking about how to combine them, and we were also trying to decide whether to come up with a list of better candidates or just say “anyone would be better than Larry Summers.”

All of a sudden, someone in our group, who had been browsing the web in search for better candidates, suddenly interjects that “Larry Summers has withdrawn from consideration for the Fed job!”

That’s some good fucking karma.

And yes, it’s a pretty awesome moment when exactly what you’re working towards comes true like that, even if it’s only one thing on a very long list.

Here’s the next thing on the list: Too Big To Fail needs to end, people. Someone named Scott Cahoon sent me a video regarding that very topic last night which advertises his book called “Too Big Has Failed,” available on Amazon.

p.s. also, it’s been 5 years since the crisis, and not enough has changed.

Learning accounting

There are lots of things I know nothing at all about. It annoys me not to understand a subject at all, because it often means I can’t follow a conversation that I care about. The list includes, just as a start: accounting, law, and politics.

Of those three, accounting seems like the easiest thing to tackle by far. This is partly because the space between what it’s theoretically supposed to be and how it’s practiced is smaller than with law or politics. Or maybe the kind of tricks accountants use seem closer to the kind of tricks I know about from being a quant, so that space seems easier to navigate for me personally.

Anyway, I might be wrong, but my impression is that my lack of understanding of accounting is mostly a language barrier, rather than a conceptual problem. There are expenses, and revenue, and lots of tax issues. There are categories. I’m working on the assumption that none of this stuff is exactly mathematical either, it’s all about knowing what things are called. And I don’t know any of it.

So I just signed up to learn at least some of it on a free Coursera course from the Wharton MBA Foundation Series. Here’s the introductory video, the professor seems super nerdy and goofy, which is a good start.

So in my copious free time I’ll be watching videos explaining the language of tax deferment and the like. Or at least that’s the fantasy – the thing about Coursera is that it’s free, so there’s not much incentive to keep up with the course. And the fact that all four Wharton 1st-year courses are being given away for free is proof of something, by the way – possibly that what you’re really paying for in business school is the connections you make while you’re there.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

You know what’s awesome? I’ll tell you what’s awesome.

What’s awesome is waking up on Saturday and knowing it’s time to crack open the Aunt Pythia Google Doc and see what juicy ethical dilemmas there are to ponder. I live for this stuff, peoples! Thank you for offering your most intimate conundrums for me to rip open and expose to the world! I do appreciate it.

If you have no idea what I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

But most importantly, Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Auntie Py,

I keep thinking of starting my own blog about my favorite ten things: data, small tricks, visualization, things that fly, you know … But I am so immersed in the 10+ great blogs out there (mathbabe to mention one), that I keep consuming and enjoying, and never get around to sitting down and producing.

What do you think is a healthy balance of reading what awesome people have to say and trying to add one’s own two cents out there? Is it ever possible to do both seriously and thoroughly?

It would be most helpful, if you could also extend your wisdom to academic publications.

May your readers grow exponentially.

Be Your Own True CHaracter

Dear BYOTCH,

Confession: I don’t regularly read anyone else’s blog. I spend quite a bit of time on Naked Capitalism, and I have historically spent quite a bit of time on Dealbreaker, although now that Matt Levine has moved to Bloomberg I am enjoying him there.

I also regularly check out a bunch of blogs, including my friend Jordan’s blog Quomodocumque, even though it’s impossible to spell. But let’s put it this way: I wasn’t aware of the moment that Google Reader disappeared, because I don’t need a reader for the kind of reading I do.

Not that I don’t read. I do read, a lot, and one way I do is I follow people on Twitter who use it like I do, mainly to post interesting links. That way I get to read all sorts of things from all sorts of sources. Also, I enjoy getting links from my readers and friends through email or chat.

So I guess my answer is, it’s just as important to diversify your reading than it is to balance reading and writing. As for writing, go here for more advice.

As for the seriously/ thoughtfully thing: don’t try too hard. In fact, the key is to have exactly one idea and write about it. If you try to have more than one idea it will be too long, too complicated, or both.

Finally, as for the academic writing: same answer. I think I wrote as many papers as I read, which is to say I didn’t read all that many papers. I mostly learned math through talking to people directly about their work and through going to talks, and early on through classes and homework. But that’s a personality thing, everyone’s different.

Good luck!

Aunt Py

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Somewhere along the line I thankfully transitioned away from seeking advice. I no longer feel any need whatsoever to seek advice on anything major, ever, as the data is now in: nobody is better at advising me than myself.

In fact I would take this a level further by declaring that any compulsion to seek advice itself represents a bigger problem than whatever one might feel the need to be asking for advice about!

My fence position on giving advice is commensurate with the above, but hey, if it makes for juicy reading, why not! 🙂

Loopy Not

Dear Loopy,

Putting aside the fact that you filled out an advice form to object to the concept of advice giving, I totally agree with you. I’d put it another way though. Often, when people think they have a question about topic A, in asking it they expose that they have a much greater need to be advised on topic B, and topic B is usually something like “how do I make important life decisions?”.

Put it another way. Religious readers of Aunt Pythia may have noticed that she consistently offers advice akin to “think for yourself!” at the rate of every second week or so. You might imagine that this means Aunt Pythia wishes her job weren’t giving advice at all, but that is false. In fact, Aunt Pythia loves her job, and wants to help people, but she often considers the best way to help is to answer the question that nobody thought to ask.

So if someone’s asking a question that they should answer themselves (“should I marry this woman that I love dearly even though so-and-so doesn’t think it will work out?”) the answer isn’t directed at the question, the answer is directed at the question of what it means to have free will.

That’s a more important and universal question anyway, and moreover talking it over in a nurturing and thoughtful environment is not a useless exercise: people have been known to emerge courageous and determined from such conversations, and they go forth boldly and make the decisions they already should have been making.

Finally, to address your defiant position on advice-giving. Putting aside the fact that you’ve given me advice on never giving advice, I will defend my occupation thus: some people get something from advice, other people ignore it. Feel free to ignore it.

Yours,

Aunt Pythia

——

Hi Babe,

I am a junior faculty in a university you know. Last semester I had an undergrad in my class who had (and still has) a crush on me. The feeling is mutual, but she chose to take another course with me, so our flirtation has gone nowhere. I am afraid that she will ask to supervise her senior thesis, which I could but don’t want to do. Instead, I want to pursue a relationship with her. Should I take her to coffee and explain my predicament?

Sad in Downtown

Dear Sad,

Hands off, buddy. You don’t know what kind of crush she has one you – it could very well be an intellectual crush, and she could be taking another course with the reasonable expectation of writing a senior thesis with you. In other words, she’s investing her time and scholarly energy into this relationship, and it’s simply not fair to her academic career for you to throw that all away because you want to get into her pants.

Think about it this way. Let’s say some man took two classes from you, and say you went out to coffee with that man to tell him you can’t do a senior thesis with him but you’d love to be his basketball buddy.

Would that be reasonable? No, it wouldn’t. And that’s the smell test here. You can’t derail her intellectual investment just because she happens to be attractive.

As for the flirting, it’s possible she does have a crush on you, but it’s also possible that she’s just psyched to get attention from a professor, and the power differential makes her willing to take that attention in any form she can. So don’t get too high on it, it’s called power.

My advice: don’t make a move on her, be her advisor, and be her advocate. If it’s meant to be then she’ll come to your office someday after she graduates, when she’s no longer at your mercy, and she’ll tell you she’s interested as one adult talks to another. But even then it’s gotta come from her.

Finally, you might want to reread the papers you signed when you took this job. They’re not window dressing.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Today, I had a substitute teacher in my linear algebra class. As he walked in, it was as if Gandalf had appeared to lead his hobbits to their destinies. Grey bearded, tall, hunched, and with an almost accusing nose as he peered out expectantly, he wielded those matrices with the ease of someone who had defeated vectors from as far away as Eigen to the East and series from Fourier to the South. As much as he was intimidating he was also reassuring in his insistence that not only could we understand the material, but that our quest was a righteous one. My question is, as a math major soon to graduate (hopefully) without any specific plans, where is my ring to toss in Mount Doom?

Love your posts!

Looking for Mount Doom

Dear Looking for Mount Doom,

You know how, when you’re an uber nerd from an uber nerd family, all those nerdy books and movies kind of make no sense to you because you’ve seen them since you were 4 and you just weren’t capable of deconstructing stuff and interpreting stuff when you were 4?

Well, your question has forced me to think about the meaning of the ring, and of Mount Doom, and who Gandalf was, and who Frodo was, and try to understand the extent to which we are all Frodos, and we each have our own ring to throw into our personal Mount Dooms, and I gotta tell you, I got nothing.

However, if I might shift the frame just a wee bit, and suggest that your linear algebra sub was probably actually Obi Wan Kenobi, not Gandalf, then this one’s easy: go find yourself a Yoda (thesis advisor) and learn how to use the force (of mathematics). And remember: there is no try, only do.

Good luck,

Auntie P

——

Before I end today’s column, I’ve got something to share with you, but only if you’re ready for it.

If you’re in a spicy mood on this Saturday morning, please check out a new advice blog my anonymous friend sent me. It’s called Never Sleep Alone, and it contains lots of wisdom about sex and dating, albeit couched in a ridiculously macho, possibly satirical (but possibly not) framework, especially in this post entitled Why You Suck And What To Do About It.

In other words, the advice is good, not all the assumptions are.

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Movie Review: Network

I watched Network last night on the advice of my friends in Occupy. More like insistence than advice, actually: they claimed I absolutely needed to see it, that it would blow me away with its prescience and wisdom.

Turns out they were absolutely right.

Here’s the thing, though. Given that Network was released in 1977, I’m hesitant to even suggest to young people today (defined as: younger than me) that they watch it because they it’s so true, its predictions are so spot-on accurate, that anyone who wasn’t alive in 1977 might not – probably cannot – appreciate how incredible it must have seemed back then. It might even seem boring to someone who is used to a world of Fox News and the internet’s filter bubble.

Then again, that’s not entirely true. It’s not just an amazing prediction about what TV and society would turn into. The other strength of the movie is that it keeps changing, in a mostly painful but sometimes hilarious way, from scene to scene, subplot to subplot, and that keeps it from being about just one idea or just one person.

A particularly powerful scene of a jilted wife really got to me, and even though the movie isn’t particularly about that relationship, the movie manages to make it work.

And the most ridiculous scene, which involves two revolutionary groups reading over a contract with a crowd of network lawyers, might also be the most convincingly depressing: we might have our own particular emotional and political issues and rebellions, but we are all cowed by the power of money.

If you wanted to force Network to be about one thing in particular, it would have to be an argument concerning the role of the individual in the modern world. Here’s the protagonist, Howard Beale, preaching to his television audience from this YouTube clip of Network:

… when the twelfth largest company in the world controls the most awesome goddamned propaganda force in the whole godless world, who knows what shit will be peddled for truth on this tube?

So, listen to me! Television is not the truth! Television is a goddamned amusement park, that’s what television is! Television is a circus, a carnival, a travelling troupe of acrobats and story-tellers, singers and dancers, jugglers, side-show freaks, lion-tamers and football players. We’re in the boredom-killing business!

If you want truth, go to God, go to your guru, go to yourself because that’s the only place you’ll ever find any real truth! But, man, you’re never going to get any truth from us.

We’ll tell you anything you want to hear. We lie like hell! We’ll tell you Kojack always gets the killer, and nobody ever gets cancer in Archie Bunker’s house. And no matter how much trouble the hero is in, don’t worry: just look at your watch — at the end of the hour, he’s going to win. We’ll tell you any shit you want to hear!

We deal in illusion, man! None of it’s true! But you people sit there — all of you — day after day, night after night, all ages, colors, creeds — we’re all you know. You’re beginning to believe this illusion we’re spinning here. You’re beginning to think the tube is reality and your own lives are unreal.

You do whatever the tube tells you. You dress like the tube, you eat like the tube, you raise your children like the tube, you think like the tube. This is mass madness, you maniacs!

In God’s name, you people are the real thing! We’re the illusions! So turn off this goddam set! Turn it off right now! Turn it off and leave it off. Turn it off right now, right in the middle of this very sentence I’m speaking now.”

After a while, the head of the news corporation decides he’s had enough of Beale’s message and decides to give him the corporation’s perspective on the discussion. From this YouTube clip:

You get up on your little twenty-one inch screen, and howl about America and democracy.

There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM and ITT and AT&T and Dupont, Dow, Union Carbide and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today.

What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state — Karl Marx? They pull out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories and minimax solutions and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments just like we do.

We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale. The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable by-laws of business.

The world is a business, Mr. Beale!

It has been since man crawled out of the slime, and our children, Mr. Beale, will live to see that perfect world in which there is no war and famine, oppression and brutality — one vast and ecumenical holding company, for whom all men will work to serve a common profit, in which all men will hold a share of stock, all necessities provided, all anxieties tranquilized, all boredom amused. And I have chosen you to preach this evangel, Mr. Beale.

What’s incredible about Network is that, until possibly the last 2 minutes, none of it seems particularly unrealistic. It’s satire that rings so true that it manages to avoid the standard skeptical or baffled response. And although it is not uplifting, Network is incredibly thought-provoking and current.

Finally, the movie also has some show-biz advice for anyone trying to communicate a message. Namely, being consistently depressing and apocalyptic gets old, even if there’s an element of truth to it. It’s critical to balance that with hope about the power of individual action, sprinkled with outrage and impulsive energy.

Interactive scoring models: why hasn’t this happened yet?

My friend Suresh just reminded me about this article written a couple of years ago by Malcolm Gladwell and published in the New Yorker.

It concerns various scoring models that claim to be both comprehensive (which means it covers the whole thing, not just one aspect of the thing) and heterogeneous (which means it is broad enough to cover all things in a category), say for cars or for colleges.

Weird things happen when you try to do this, like not caring much about price or exterior detailing for sports cars.

Two things. First, this stuff is actually really hard to do well. I like how Gladwell addresses this issue:

At no point, however, do the college guides acknowledge the extraordinary difficulty of the task they have set themselves.

Second of all, I think the issue of combining heterogeneity and comprehensiveness is addressable, but it has to be addressed interactively.

Specifically, what if instead of a single fixed score, there was a place where a given car-buyer or college-seeker could go to fill out a form of preferences? For each defined and rated aspect, the user would fill answer a question about how much they cared about that aspect. They’d assign a weight to each aspect. A given question would look something like this:

For colleges, some people care a lot about whether their college has a ton of alumni giving, other people care more about whether the surrounding town is urban or rural. Let’s let people create their own scoring system. It’s technically easy.

I’ve suggested this before when I talked about rating math articles on various dimensions (hard, interesting, technical, well-written) and then letting people come and search based on weighting those dimensions and ranking. But honestly we can start even dumber, with car ratings and college ratings.

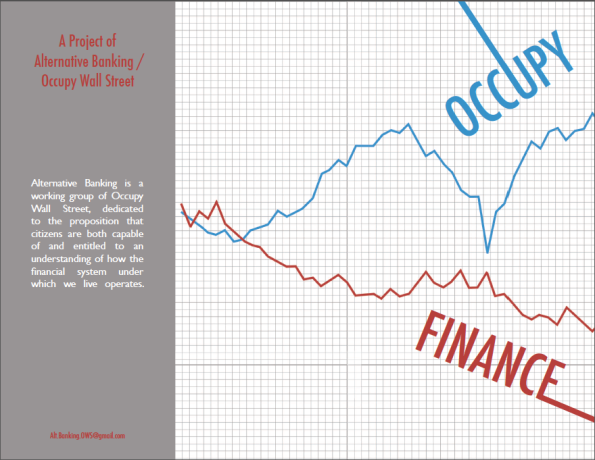

Occupy Finance the book, coming out next Tuesday (#OWS)

Holy shit I’m just about bursting with pride to announce that my Occupy group’s book, Occupy Finance, is coming out Tuesday and is at the printer right now.

This is thanks in large part to all of you awesome people who sent contributions for the printing. You guys totally rock.

Our plan is to meet in Zuccotti Park Tuesday morning, September 17th, which is the 2nd anniversary of the occupation, give a wee press conference at 10am or so, and then hand out hundreds of copies of the book to whomever shows up.

Here’s the wrap-around cover to give you just a taste:

See you guys on Tuesday! The event is also on Facebook.

Working in the NYC Mayor’s Office

I recently took a job in the NYC Mayor’s Office as an unpaid consultant. It’s an interesting time to be working for the Mayor, to be sure – everyone’s waiting to see what happens this week with the election, and all sorts of things are up in the air. Planning essentially stops at December 31st.

I’m working in a data group which deals with social service agency data. That means Child Services, Homeless Services, and the like. Any agency where there there is direct contact with lots of people and their data. The idea is for me to help them out with a project that, if successful, I might be able to take to another city as a product. I’m still working full-time at the same job.

Specifically, my goal is to figure out a way to use data to help the people involved – the homeless, for example – get connected to better services. As a side effect I think this should make the agency more efficient. Far too many data studies only care about efficiency – how to make do with fewer police or fewer ambulances – with no thought or care about whether the people experiencing the services are being affected. I want to start with the people, and hope for efficiency gains, which I believe will come.

One thing that has already amazed me about this job, which I’ve just started, is the conversations people have about the ethics of data privacy.

It is a well-known fact that, as you link more and more data about people together, you can predict their behavior better. So for example, you could theoretically link all the different agency data for a given person into a profile, including crime data, health data, education and the like.

This might help you profile that person, and that might help you offer them better services. But it also might not be what that person wants you to do, especially if you start adding social media information. There’s a tension between the best model and reasonable limits of privacy and decency, even when the model is intended to be used in a primarily helpful manner. It’s more obvious when you’re attempting something insidious like predictive policing, of course.

Now, it shouldn’t shock me to have such conversations, because after all we are talking about some of the most vulnerable populations here. But even so, it does.

In all my time as a predictive modeler, I’ve never been in that kind of conversation, about the malicious things people could do with such-and-such profile information, or with this or that model, unless I started it myself.

When you work as a quant in finance, the data you work with is utterly sanitized to the point where, although it eventually trickles down to humans, you are asked to think of it as generated by some kind of machine, which we call “the market.”

Similarly, when you work in ad tech or other internet modeling, you think of users as the targets of your predatory goals: click on this, user, or buy that, user! They are prey, and the more we know about them the better our aim will be. If we can buy their profiles from Acxiom, all the better for our purposes.

This is the opposite of all of that. Super interesting, and glad I am being given this opportunity.

The art of definition

Definitions are basic objects in mathematics. Even so, I’ve never seen the art of definition explicitly taught, and I have rarely seen the need for a definition explicitly discussed.

Have you ever noticed how damn hard it is to make a good definition and yet how utterly useful a good definition can be?

The basic definitions inform the research of any field, and a good definition will lead to better theorems than a bad one. If you get them right, if you really nail down the definition, then everything works out much more cleanly than otherwise.

So for example, it doesn’t make sense to work in algebraic geometry without the concepts of affine and projective space, and varieties, and schemes. They are to algebraic geometry like circles and triangles are to elementary geometry. You define your objects, then you see how they act and how they interact.

I saw first hand how a good definition improves clarity of thought back in grad school. I was lucky enough to talk to John Tate (my mathematical hero) about my thesis, and after listening to me go on for some time with a simple object but complicated proofs, he suggested that I add an extra sentence to my basic object, an assumption with a fixed structure.

This gave me a bit more explaining to do up front – but even there added intuition – and greatly simplified the statement and proofs of my theorems. It also improved my talks about my thesis. I could now go in and spend some time motivating the definition, and then state the resulting theorem very cleanly once people were convinced.

Another example from my husband’s grad seminar this semester: he’s starting out with the concept of triangulated categories coming from Verdier’s thesis. One mysterious part of the definition involves the so-called “octahedral axiom,” which mathematicians have been grappling with ever since it was invented. As far as Johan tells it, people struggle with why it’s necessary but not that it’s necessary, or at least something very much like it. What’s amazing is that Verdier managed to get it right when he was so young.

Why? Because definition building is naturally iterative, and it can take years to get it right. It’s not an obvious process. I have no doubt that many arguments were once fought over whether the most basic definitions, although I’m no historian. There’s a whole evolutionary struggle that I can imagine could take place as well – people could make the wrong definition, and the community would not be able to prove good stuff about that, so it would eventually give way to stronger, more robust definitions. Better to start out carefully.

Going back to that. I think it’s strange that the building up of definitions is not explicitly taught. I think it’s a result of the way math is taught as if it’s already known, so the mystery of how people came up with the theorems is almost hidden, never mind the original objects and questions about them. For that matter, it’s not often discussed why we care whether a given theorem is important, just whether it’s true. Somehow the “importance” conversations happen in quiet voices over wine at the seminar dinners.

Personally, I got just as much out of Tate’s help with my thesis as anything else about my thesis. The crystalline focus that he helped me achieve with the correct choice of the “basic object of study” has made me want to do that every single time I embark on a project, in data science or elsewhere.

Sunday morning musing: is sexism an addiction?

I’ve been reading articles about cultures of sexism at Harvard Business School and in philosophy, both articles published in the New York Times this past week. The two of them have gotten me to speculate about the different ways that men and women experience sexist behavior.

Namely, very differently. Women, being the targets of sexist remarks and behavior, are sensitive to its barbaric nature and status-oriented putdowns – they are aware of it because it so obviously stings. Men – some men, not all – consistently seem baffled by all the fuss, and if they acknowledge the behavior, it is, in their opinion, more like having fun than being mean.

“Why would people want me to stop having fun?” they ask.

It makes me wonder if sexism is addictive. Let me explain my Sunday morning theory.

Assume that, when men perform an act of sexism, they get rewarded in their pleasure center similar to when someone takes a street drug or has sex.

So for example, say some male Harvard Business School (HBS) student encounters a female HBS colleague who is a potential competitor. To establish his dominance, he puts her down publicly on the basis of her looks. As mentioned in the article, the HBS population is obsessed with status, and this is a standard way of keeping her status low and simultaneously making her anxious and distracted.

My question is, what happens inside that man’s brain when he does that? For that matter, what happens to the brains of the other men in that group who witness that? My theory is that they all experience a kind of pleasure center stimulation, whereby their entire group is nudged up in rank over some “other,” which happens to be that woman. In some sense it’s kind of irrelevant who they put down in order to be rewarded, though, which is why they don’t think of what they did as a bad thing, just something that they vaguely enjoyed.

Go back to how differently the men and women describe their experiences after the fact of sexist environments. Men consistently don’t remember it as a negative event. From the article about sexism in philosophy:

I’m always hearing from stressed-out men, worrying aloud what “all this fuss” about sexual harassment means for them. I’ve heard it at training sessions on university sexual harassment policy: “Does this mean I can’t even tell a woman that she looks nice?” I’ve heard it in coffee lounges: “Make sure you keep your door open when you’re talking to a woman student — you never know what she might say later.” And I’ve had it confided to me, with a sigh of regret, at conference happy hours: “I’m afraid now to form any relationships with female students — they might take it the wrong way.”

I don’t think men are lying. I think they actually experience sexist events as positive and benign.

It also makes sense how men react when sexism is addressed by the higher authorities in the form of sensitivity training. When men are forced into a room to talk about sexism and norms of appropriate behavior, they’re super uncomfortable and don’t seem to know why they’re there (again, not all men). They for whatever reason don’t think discussions about sexism apply to them, like it’s a women’s issue.

On the other hand, as we saw in the HBS article, forcing men to talk about it at length does seem to actually help, in spite of their protests. The article focuses on women’s behavior, I think overly much, but it’s just as much about men as it is about women. True, women undermine themselves by competing with each other to be perfect and sexy and brilliant (but not too brilliant), etc., but really it’s about getting them men to stop with their nonsense, right?

And what might be happening is that, along with the positive feedback which stimulates the pleasure center, through this training they might also be developing a second, negative feedback around sexist comments, which would mean that eventually, if that second feedback grew strong enough, it would no longer feel so good to be sexist.

I mean, how do you break someone of their addictive habits? I guess you could destroy the pleasure center altogether, but that seems extreme except for the really most annoying HBS folks. Probably what you’d want to do is counteract the effect with an opposing effect. Thus sensitivity training.

Of course, this theory applies equally well to other forms of discrimination. And it’s not obvious how to address it even if it’s true. But at least, if we thought about it this way, it would throw light on the baffling disconnect whereby such problems are glaringly obvious to some while remaining utterly invisible to others.

Ask Aunt Pythia

Aunt Pythia’s mailbox has been satisfyingly full this week, and she thanks you all for your questions. Please keep them coming, she looks forward to Saturdays ever so much.

Go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

And please, Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I want to pursue a career as a data scientist. I am very comfortable with maths and statistics and love spending time with large data sets. However, I don’t have any background in programming. I am wondering what all I can do in the next 12-18 months to be a pro in this field and whether a degree is data science the way to go about it.

Future Data Scientist

Dear FDS,

First of all, I feel like I’m being set up by Miss Disruption on this question, whose answer is always “learn to code” and who came out with another hilarious advice column this past week (best line: “Instead of putting your trust in what you think looks like Mark Zuckerberg, put your trust in numbers. Numbers that will tell you how much someone looks like Mark Zuckerberg.”).

Second of all, I think you need to learn to code. It’s fun, and the number of resources available nowadays is outrageous. Plus you don’t have to be a really good coder to be a data scientist (I know, I’ve just offended a bunch of people). You just need to be able to get the data into usable format, which is tricky, and then you need to know what to do with it – it’s much more about questions of what to do than it is about questions of whether your code looks great, at least when you’re working on your own projects.

Depending on your preferred learning style, I’d say get a classic CS text and read it, or take some free courses online, or just start on a project and refer to examples to learn how to do specific tasks.

Oh, and first install Anaconda.

Good luck!

Cathy

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

A decade ago I had a bad breakup with my first girlfriend (in which I felt I was largely at fault). After a while, she wanted to continue being friends, but I found this too difficult and told her never to contact me again. Over the years, I made peace with myself, and periodically thought of contacting her to apologize, but always held back (note: I never once had any intention of getting back with her romantically).

Now, I’ve been married for years, and it’s also been years since she’s been married with a kid (I know only because of a mutual friend), and for some reason she sent me a friend request on Facebook.

- Because of our mutual friends on Facebook, both our existences on Facebook are clear; I have never sent her a friend request, however.

- This a violation of my old request not to be contacted.

- I’m over that old request and don’t have a problem with resuming some minimal contact in the form of “Facebook friend”.

- I asked my wife if it’s OK, and she got weird about it, and we concluded that therefore it’s not OK.

- I was considering sending her a message that my wife said it’s not OK.

- My wife thinks that would be weird and I should ignore her.

- I don’t want to just ignore her but want to at least finally say I’m sorry for the things I said in the last communication we had a decade ago.

What is Facebook Etiquette?

Dear What,

This has nothing to do with Facebook, except in that it happens to be the medium for your potential exchange with your ex. It’s really about your regrets about your past behavior to this woman.

I’m going to respond to your points in turn.

- If I’m her, I think it’s super safe to ask to be your friend since we’re both married now.

- Who the hell thinks a decade-old request like that still holds? That’s just plain weird.

- How kind and generous of you! Not really.

- Sounds to me like you’re trying to make your wife take responsibility here for your stuff.

- That’s super ridiculous. Either man up and be her friend or leave her alone.

- Again with what the wife thinks. Think for yourself!

- If you really want to apologize, just do it.

This is something you either need to own, and do it right, either on Facebook or by email, since you presumably could get her email via a common friend, or you need to put to bed and forget about. I’m sure she’d prefer the former (and I’m guessing that you would too, at least once you got yourself to do it) but is already making do with the latter. What you don’t do is send her some crapola about how you “can’t be Facebook friends with her” because of your wife. That’s nuts.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Auntie P,

I think sex is awesome. How do I have more of it?

I am in a very stable, loving relationship for over a decade, with all the kids and stuff that happens when you spend so long with someone (and I love all it). We have good sex, sometimes great sex, but we only rarely have amazing sex. Here are some specific questions for you:

1. I want sex a lot more often than my partner. That’s a bit frustrating, what should I do?

2. I’d love to try something different. Not too crazy, but different. We know each other too well and are more often than not following into the routine of “efficient sex”, going for the kill. What do I do?

3. With kids, a busy job, lots of hobbies and other stuff, and not enough sleep, how do you make time for long sex sessions? I’ve never tried cocaine, should I begin?

Thanks for the tips,

Perverse Bundle

——

Dear PB,

First of all, you are not alone. This is about the most common complaint I hear from my friends in happy marriages. First, be proud that it’s as good as it is!

Next, the truth is, no two people have exactly the same sex drive, and over time the mismatch of desire gets worse due to the natural form of complementary schismogenesis which exists in practically every sexual relationship.

That is to say, the man or woman who wants more sex, even if it’s just a little bit more, starts to feel rejected, and has moments of aggressiveness and hostility surrounding their unmet desire, which makes the man or woman who wants less sex feel even less like it, and the ante gets upped, and the cycle continues. It’s a feedback loop that often spirals out of control.

It doesn’t even sound like that’s where you are, but it’s a danger because it’s always a danger.

How does one build a dampening effect to counteract this schismogenesis? Maybe it would be possible to explicitly funnel your unmet desires into some other activity where you get attention, though possibly not sexual attention.

So, you could have friends over regularly for parties with your partner, or you could go out with your friends regularly, or you could get ambitious and start playing the guitar and go out to do open mics, or you could even join a band. The point is that you get fun stuff to do and not enough time to dwell on being rejected, and moreover your partner will find you irresistibly cute and brave and sexy once you’re up on stage.

Next, when you’re super busy with kids and national tours from your new music career, long sex sessions don’t happen by themselves. You need to make time for them, in the form of date nights. And dates can happen inside bedrooms, but even so, call them “date nights” since that sounds better than “scheduled sex”.

Finally: say no to cocaine, but do buy sex toys.

Good luck!

Auntie P

——

Dear Auntie,

I’m not always as good a parent as I’d like myself to be. I’m trying to reason with my 3 kids who are all younger than 4, but they always go too far and I end up yelling too often. I NEVER yell at anyone else, though. I know exactly the kind of situations that trigger the yelling, but they’re unavoidable. What should I do?

Uncle Stach

Dear Uncle Stach,

First, I have an enormous amount of sympathy for anyone dealing with even one kid, never mind three. So give yourself a break, and try try again, every morning. It’s a life-long job and it’s totally possible to slowly improve your techniques over time.

Second, I think I know what your problem is: namely, there’s no reasoning with kids under 4 years old. There’s ritual and rules, and depending on how old they are and how consistently you proceed with those rituals and rules, they might or might not be familiar with how things are going to work out. My advice is to choose a ritual (going to bed seems to be a good one) and make sure it is incredibly consistent and early (say 6:30 or 7:00 pm, no kidding) and do the exact same thing every day for two weeks with all your kids. Getting a good night’s sleep is absolutely vital for being able to handle the next day. Once you’ve got that ritual down, introduce other rituals and slowly create a world for them which is embedded with rituals, which kids totally adore.

As for reasoning: you can start reasoning with kids once they’re in school. Before that, just give them the choice of two options: drawing or jigsaw puzzle, playground or sprinklers, do what I want or do what I really want.

Third, there’s yelling and then there’s yelling. What you absolutely cannot do is get abusive when you yell. Stuff like “you’re stupid” or “you’re lazy” has been shown to be as damaging for teenagers as physical abuse, so don’t do it. Don’t shame kids or insult them, ever. If you find yourself tempted to make blanket negative statements, take five and go to the bathroom. When they do nasty things, by all means make them apologize for those actions, but never let those actions define them.

On the other hand, a stern tone of voice when you tell your 3-year-old to sit in her chair until dinner is over it totally appropriate, as long as it doesn’t turn into a screaming match. As for screaming: my advice is to ignore screams, and if they don’t dissipate, put kids in their rooms so at least it’s not as loud. Never give in to a screaming kid, that’s like asking them to scream.

Finally, here’s a book I really got a lot out of: Healthy Sleep Habits, Happy Child. Explained to me how to get my babies to sleep 12 hours a night, which they pretty much still do.

Good luck! And enjoy them!!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Simons Center for Data Analysis

Has anyone heard of the new Simons Center for Data Analysis?

Neither had I until just now. But some guy named Leslie Greengard, who is a distinguished mathematician and computer scientist, just got named its director (hat tip Peter Woit).

Please inform me if you know more about this center. I got nothing except this tiny description:

As SCDA’s director, Greengard will build and lead a team of scientists committed to analyzing large-scale, rich data sets and to developing innovative mathematical methods to examine such data.

Experimentation in education – still a long way to go

Yesterday’s New York Times ran a piece by Gina Kolata on randomized experiments in education. Namely, they’ve started to use randomized experiments like they do in medical trials. Here’s what’s going on:

… a little-known office in the Education Department is starting to get some real data, using a method that has transformed medicine: the randomized clinical trial, in which groups of subjects are randomly assigned to get either an experimental therapy, the standard therapy, a placebo or nothing.

They have preliminary results:

The findings could be transformative, researchers say. For example, one conclusion from the new research is that the choice of instructional materials — textbooks, curriculum guides, homework, quizzes — can affect achievement as profoundly as teachers themselves; a poor choice of materials is at least as bad as a terrible teacher, and a good choice can help offset a bad teacher’s deficiencies.

So far, the office — the Institute of Education Sciences — has supported 175 randomized studies. Some have already concluded; among the findings are that one popular math textbook was demonstrably superior to three competitors, and that a highly touted computer-aided math-instruction program had no effect on how much students learned.

Other studies are under way. Cognitive psychology researchers, for instance, are assessing an experimental math curriculum in Tampa, Fla.

If you go to any of the above links, you’ll see that the metric of success is consistently defined as a standardized test score. That’s the only gauge of improvement. So any “progress” that’s made is by definition measured by such a test.

In other words, if we optimize to this system, we will optimize for textbooks which raise standardized test scores. If it doesn’t improve kids’ test scores, it might as well not be in the book. In fact it will probably “waste time” with respect to raising scores, so there will effectively be a penalty for, say, fun puzzles, or understanding why things are true, or learning to write.

Now, if scores are all we cared about, this could and should be considered progress. Certainly Gina Kolata, the NYTimes journalist, didn’t mention that we might not care only about this – she recorded it as unfettered good, as she was expected to by the Education Department, no doubt. But, as a data scientist who gets paid to think about the feedback loops and side effects of choices like “metrics of success,” I have a problem with it.

I don’t have a thing against randomized tests – using them is a good idea, and will maybe even quiet some noise around all the different curriculums, online and in person. I do think, though, that we need to have more ways of evaluating an educational experience than a test score.

After all, if I take a pill once a day to prevent a disease, then what I care about is whether I get the disease, not which pill I took or what color it was. Medicine is a very outcome- focused discipline in a way that education is not. Of course, there are exceptions, say when the treatment has strong and negative side-effects, and the overall effect is net negative. Kind of like when the teacher raises his or her kids’ scores but also causes them to lose interest in learning.

If we go the way of the randomized trial, why not give the students some self-assessments and review capabilities of their text and their teacher (which is not to say teacher evaluations give clean data, because we know from experience they don’t)? Why not ask the students how they liked the book and how much they care about learning? Why not track the students’ attitudes, self-assessment, and goals for a subject for a few years, since we know longer-term effects are sometimes more important that immediate test score changes?

In other words, I’m calling for collecting more and better data beyond one-dimensional test scores. If you think about it, teenagers get treated better by their cell phone companies or Netflix than by their schools.

I know what you’re thinking – that students are all lazy and would all complain about anyone or anything that gave them extra work. My experience is that kids actually aren’t like this, know the difference between rote work and real learning, and love the learning part.

Another complaint I hear coming – long-term studies take too long and are too expensive. But ultimately these things do matter in the long term, and as we’ve seen in medicine, skimping on experiments often leads to bigger and more expensive problems. Plus, we’re not going to improve education overnight.

And by the way, if and/or when we do this, we need to implement strict privacy policies for the students’ answers – you don’t want a 7-year-old’s attitude about math held against him when he of she applies to college.

Entrepreneurship versus the state

I really like this Slate article written by Mariana Mazzucato and entitled It’s a Myth That Entrepreneurs Drive New Technology.

In it she makes the point that lobbyists for tech companies have overemphasized the role of the entrepreneur in our nation’s technological advances, and likewise underemphasized the role of the state. From the article:

Whether an innovation will be a success is uncertain, and it can take longer than traditional banks or venture capitalists are willing to wait. In countries such as the United States, China, Singapore, and Denmark, the state has provided the kind of patient and long-term finance new technologies need to get off the ground. Investments of this kind have often been driven by big missions, from putting a human on the moon to solving climate change. This has required not only funding basic research—the typical “public good” that most economists admit needs state help—but applied research and seed funding too.

One of her examples was the internet itself, which brings me back – my mom was involved with that project.

Some of my earliest memories are going with my mom to fix something at BBN where she had superuser access on the internet back when it was populated by very few people – the president and some army generals. And no, she didn’t have any kind of clearance, they didn’t think very hard about computer security back then, but on the other hand my mom is scrupulously honest and would never read anyone else’s mail. And it was all done through DARPA or other Department of Defense funding.

Funny story. When I was little, my mom was in charge (with some other people, on a rotation) of keeping the internet running, which she would refer to as “being on call”. She’d leave, sometimes in the middle of the night, to get these massive computers booted back up. I’d go with her if nobody else was around to watch me, and I remember she’d sometimes get underneath these massive metal boxes, and I’d just see her feet sticking out at the bottom, not unlike a mechanic under a car at a garage.

Anyway, the story is that one time she was on call on Christmas Eve and got called in on an emergency, and in my stocking the next morning I got “IOU” notes. That makes for a pretty crappy Christmas morning when you’re 8! My personal sacrifice for the internet.

Going back to the “state vs. entrepreneur” debate. One thing Mazzucato didn’t mention, but that I will, is the issue of waste. People talk all the time about how wasteful the state is – how there are too many people, and they don’t do much, and they never get fired – but they don’t appreciate how very wasteful the world of start-ups is. Most new companies fail entirely and never do anything at all constructive. I personally have seen hundreds of people working on projects for years in the realm of “entrepreneurs” that everyone knows will do nothing. Talk about waste!

Next, let’s go to why this all happens. It’s all about taxes. From the article:

In this era of obsession with reducing public debt—and the size of the state more generally—it is vital to dispel the myth that the public sector will be less innovative than the private sector. Otherwise, the state’s ability to continue to play its enterprising role will be weakened. Stories about how progress is led by entrepreneurs and venture capitalists have aided lobbyists for the U.S. venture capital industry in negotiating lower capital gains and corporate income taxes—hurting the ability of the state to refill its innovation fund.

Totally agreed. It’s a beautiful story aimed at confusing people about whether Apple or Google or GE should pay any taxes at all.

But here’s where I don’t follow her, when she suggests a possible solution:

It is time for the state to get something back for its investments. How? First, this requires an admission that the state does more than just fix market failures—the usual way economists justify state spending. The state has shaped and created markets and, in doing so, taken on great risks. Second, we must ask where the reward is for such risk-taking and admit that it is no longer coming from the tax systems. Third, we must think creatively about how that reward can come back.

There are many ways for this to happen. The repayment of some loans for students depends on income, so why not do this for companies? When Google’s future owners received a grant from the NSF, the contract should have said: If and when the beneficiaries of the grant make $X billion, a contribution will be made back to the NSF.

It’s not that I don’t like the idea in principle. But a problem with the corporation/ people debate is that one critical way that corporations are not like people is in terms of long-term liability. People work at corporations, and when it’s convenient for them, they leave and go somewhere else or start a new company (whereas it’s harder to change bodies). That makes sense in many situations, but it wouldn’t be consistent with her tax-me-when-you-get-rich plan.

In other words, say I form a company that gets NSF funding, comes up with something brilliant, and starts to make huge profits. Then, in order to avoid losing any of my hard-earned dough, I dissolve my company, fire most of the workers, and then start up a new company that doesn’t owe anything to the NSF. I can’t see how this doesn’t happen, and I can’t see how the NSF fights back against it. Lawyers, please explain why I’m wrong.

Personally, I think the real solution is to stop listening to lobbyists and raise taxes, or at the very least make the tax rates effective rather than nominal.

Short your kids, go long your neighbor: betting on people is coming soon

Yet another aspect of Gary Shteyngart’s dystopian fiction novel Super Sad True Love Story is coming true for reals this week.

Besides anticipating Occupy Wall Street, as well as Bloomberg’s sweep of Zuccotti Park (although getting it wrong on how utterly successful such sweeping would be), Shteyngart proposed the idea of instant, real-time and broadcast credit ratings.

Anyone walking around the streets of New York, as they’d pass a certain type of telephone pole – the kind that identifies you via your cell phone and communicates with data warehousing services and databases – would have their credit rating flashed onto a screen. If you went to a party, depending on how you impressed the other party go-ers, your score could plummet or rise in real time, and everyone would be able to keep track and treat you accordingly.

I mean, there were other things about the novel too, but as a data person these details certainly stuck with me since they are both extremely gross and utterly plausible.

And why do I say they are coming true now? I base my claim on two news stories I’ve been sent by my various blog readers recently.

[Aside: if you read my blog and find an awesome article that you want to send me, by all means do! My email address is available on my “About” page.]

First, coming via Suresh and Marcos, we learn that data broker Acxiom is letting people see their warehoused data. A few caveats, bien sûr:

- You get to see your own profile, here, starting in 2 days, but only your own.

- And actually, you only get to see some of your data. So they won’t tell you if you’re a suspected gambling addict, for example. It’s a curated view, and they want your help curating it more. You know, for your own good.

- And they’re doing it so that people have clarity on their business.

- Haha! Just kidding. They’re doing it because they’re trying to avoid regulations and they feel like this gesture of transparency might make people less suspicious of them.

- And they’re counting on people’s laziness. They’re allowing people to opt out, but of course the people who should opt out would likely never even know about that possibility.

- Just keep in mind that, as an individual, you won’t know what they really think they know about you, but as a corporation you can buy complete information about anyone who hasn’t opted out.

In any case those credit scores that Shteyngart talks about are already happening. The only issue is who gets flashed those numbers and when. Instead of the answers being “anyone walking down the street” and “when you walk by a pole” it’s “any corporation on the interweb” and “whenever you browse”.

After all, why would they give something away for free? Where’s the profit in showing the credit scores of anyone to everyone? Hmmmm….

That brings me to my second news story of the morning coming to me via Constantine, namely this TechCrunch story which explains how a startup called Fantex is planning to allow individuals to invest in celebrity athletes’ stocks. Yes, you too can own a tiny little piece of someone famous, for a price. From the article:

People can then buy shares of that player’s brand, like a stock, in the Fantex-consumer market. Presumably, if San Francisco 49ers tight end Vernon Davis has a monster year and looks like he’s going to get a bigger endorsement deal or a larger contract in a few years, his stock would rise and a fan could sell their Davis stock and cash out with a real, monetary profit. People would own tracking or targeted stocks in Fantex that would depend on the specific brand that they choose; these stocks would then rise and fall based on their own performance, not on the overall performance of Fantex.

Let’s put these two things together. I think it’s not too much of a stretch to acknowledge a reason for everyone to know everyone else’s credit score! Namely, we can can bet on each other’s futures!

I can’t think of any set-up more exhilarating to the community of hedge fund assholes than a huge, new open market – containing profit potentials for every single citizen of earth – where you get to make money when someone goes to the wrong college, or when someone enters into an unfortunate marriage and needs a divorce, or when someone gets predictably sick. An orgy in the exact center of tech and finance.

Are you with me peoples?!

I don’t know what your Labor Day plans are, but I’m getting ready my list of people to short in this spanking new market.

Ask Aunt Pythia

Every week, I look into Aunt Pythia’s official Google spreadsheet (it’s true she lives a super glamorous life) and every week I expect it to be my last, since at the end of the day I have fewer leftover questions than will last a week.

And yet… and yet. Somehow questions wander in, over the week, one on Tuesday, one on Friday, and when I open it up again, voila! I have a columns-worth of bad advice to spew forth once again. It’s like a tiny, possibly negative miracle.

That is not to say, dear readers, that you shouldn’t be worried about the rate of question asking!! Please do take it upon yourself to be involved!

And just in case it wasn’t clear, anything’s fair game. From “How do I get my kids to eat broccoli?” to “How do I stop fantasizing about living forever and focus on enjoying my life now?” I’m prepared to give step-by-step, humorous and mostly irrelevant suggestions.

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

And please, Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am single and I rely on masturbating to satisfy my sexual urges, but it feels kind of heartless and empty. Could porn help? Or, do I actually need to go out and find a partner?

Really Sad

Dear Really Sad,

It depends on what you mean by “help”. If you mean, “can porn make my solo masturbation sessions more efficient?”, I’d have to say “yes, for sure.” I’d also say that if you managed to figure out how to ask Aunt Pythia a question but haven’t figured out how to experiment with porn, then I can understand why you’re sad.

In terms of avoiding heartless emptiness, meeting a real life person is probably key. Plus they might like watching porn with you.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dearest Auntie P,

I just started having great sex with one of my best friends, and although we both have other sexual partners, we’re both digging this new fling. Do you have any suggestions for sex positions or other things we can throw in to make our sexual relations even more exciting? (We’re both math nerds, so we already have the nerd pillow talk thing going on, but suggestions there would also be awesome.)

Nerdelicious

Dear Nerdilicious,

Oooh oooh!! I got something!

Go on a date at the Museum of Math. I went there the other week over my lunch break, since I work about 2 blocks away, and I was like, what is this museum good for except maybe school field trips and nerd dates?

I couldn’t come up with anything, and since I saw lots of field trips I think it’s high time we cue you cuties. Momath.org, check it out. Please take pics of yourselves making out in every single exhibit, that place could use some sexing up. The gift shop’s great, though, lots of puzzles.

Wait, what if you don’t live in New York? Turns out there are plenty of people with that attribute, especially people who live in Guangzhou China, which as I’ve recently learned is absolutely massive.

In that case, I’d say that, to stay with the theme of sexing it up in public, I’d encourage you to look around for a straight-up puzzle store, some place that sells D&D starter kits with lots of different colored dice possibilities. Look, we need to give young nerds hope that someday they’ll get laid, and you guys are now their role models, including perhaps the guy above who asked the first question.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

A question from a person who is realizing a bit too late that academia is not gonna do it for him:

What kind of non-academic jobs are there for mathematicians (beyond PhD, even postdoc) that do not involve a lot of coding/programming, but otherwise do involve their problem solving abilities?

If you have discussed this question at length in your blog already, I am sorry for not reading regularly, and I’d appreciate a link to the relevant posts.

Thanks a lot!

Lost Academic

Dear Lost,

I’d say, learn to code! After all, coding is just a specific way of formally solving problems in a language that computers can understand. I’d say if you’re really a mathematician with a Ph.D. then learning to code should be pretty easy. Don’t be afraid of it, and for sure don’t be thinking you’re above it.

As far as how to learn to code, pick up a book or take an online class or just pick a project and a language (python) and a start puzzling it out. There are so many resources nowadays, you get to decide what works for you. What doesn’t work for you or your job prospects, though, is refusing to learn to code.

Good luck,

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

This isn’t a question, rather an experience.

I had the most fulfilling dream last night: I bought a pair of pants from a thrift shop that once belonged to you, Aunt Pythia, and discovered after purchasing them that you left some rather important mail in the pockets (there was also an old package in there too… I don’t remember the precise geometry of these pants).

So anyway, I had to get in touch with you and you agreed to meet me in person. So I could return to you the mail. That you left in your old pants. That you gave away to a thrift store. The point being that I got to ask you all my nerdy Aunt Pythia questions over a beer while giving it back. The end.

Love,

Dreamer

Dear Dreamer,

Holy shit, I had that same dream!

No, just kidding, I didn’t. But if that was a bizarre way of asking me to have a beer with you, then I think I’ll have to say yes. But I fully expect you to return my mail as well as my package, thanks.

Lovey dovey,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

When to go on the record with email at work

I hear lots of people, mostly young, saying they’re not going to say something by email, as a default condition, in order to avoid documenting something awkward. If it’s controversial or if the subject makes them at all uncomfortable, they’re prone to trying to have that conversation by phone or in person. They avoid email.

I get that. After all, in this age of digital records, nothing ever goes away. If they’re going to say something they don’t want to be held to, then it’s only natural they’d not want to do it in a permanent way. On the other hand, if you’re saying something you want other people held to, that’s another story.

More than half the time, when I’m witness to this issue, I’ve noticed it’s actually the wrong decision, and it ends up protecting the wrong person’s interest. People should realize that documenting sensitive issues is often just as important, and often to your advantage, as not documenting sensitive issues. It also clarifies things and avoids prolonged misunderstandings.

Two made-up examples to demonstrate how to use email.

So, say you feel like your contributions to a long-term project are being ignored, and other people are starting to jockey for credit for your work. Here’s my advice. Write an email to everyone in the project and mention that you’ve done A, B, and C, and are planning to work on D. Don’t complain or whine about how much work you’ve done, but mention specifics, along with the number of hours you’re putting in.

It might seem slightly weird, but feel free to make some excuse for it like you “just want to check in and see where people are on the project or something, since there hasn’t been much of a formal effort to keep track of stuff”, and invite other people to also document their work. Force clarity. It’s good for you, not bad, to have clarity. If people don’t want to give you credit for something, they’ll have to write back and explain themselves, which is unlikely.

Second example, the opposite of the first. Say someone has written an email which documents something which you don’t agree with that involves you. Say, for example, that someone writes to a group of people saying they agreed with you on such-and-such a deal (“Cathy has agreed to work on A”), which didn’t actually happen.

Instead of going to talk to that person, just write back to the entire group saying what the actual deal is (“Actually, there’s been a misunderstanding, and I am not planning to work on A”). You should clarify quickly and often, because you need to realize that other people use email as a way of documenting stuff too. If you ignore that email, people will assume you actually did agree to that.

I don’t want to sound like a lawsuit waiting to happen – I’ve never actually been involved in a lawsuit. But by thoughtfully documenting stuff before it becomes an issue I definitely think I’ve consistently avoided problems becoming worse, especially problems related setting expectations.

Finally, if someone has done something really inappropriate, like sexual misconduct or harassment or something, document it, even just to yourself. Send yourself an email saying exactly what happened, like a journal entry. You might need that documentation later, and now you have an exact timestamp on how things went down.

Summers’ Lending Club makes money by bypassing the Equal Credit Opportunity Act

Don’t know about you, but for some reason I have a sinking feeling when it comes to the idea of Larry Summers. Word on the CNBC street is that he’s about to be named new Fed Chair, and I am living in a state of cognitive dissonance.

To distract myself, I’m going to try better to explain what I started to explain here, when I talked about the online peer-to-peer lending company Lending Club. Summers sits on the board of Lending Club, and from my perspective it’s a logical continuation of his career of deregulation and/or bypassing of vital regulation to enrich himself.

In this case, it’s a vehicle for bypassing the FTC’s Equal Credit Opportunities Rights. It’s not perfect, but it “prohibits credit discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age, or because you get public assistance.” It forces credit scores to be relatively behavior based, like you see here. Let me contrast that to Lending Club.

Lending Club also uses mathematical models to score people who want to borrow money. These act as credit scores. But in this case, they use data like browsing history or anything they can grab about you on the web or from data warehousing companies like Acxiom (which I’ve written about here). From this Bloomberg article on Lending Club:

“What we’ve done is radically transform the way consumer lending operates,” Laplanche says in his speech. He says that LendingClub keeps staffing low by using algorithms to screen prospective borrowers for risk — rejecting 90 percent of them – – and has no physical branches like banks. “The savings can be passed on to more borrowers in terms of lower interest rates and investors in terms of attractive returns.”

I’d focus on the benefit for investors. Big money is now involved in this stuff. Turns out that bypassing credit score regulation is great for business, so of course.

For example, such models might look at your circle of friends on Facebook to see if you “run with the right crowd” before loaning you money. You can now blame your friends if you don’t get that loan! From this CNN article on the subject (hat tip David):

“It turns out humans are really good at knowing who is trustworthy and reliable in their community,” said Jeff Stewart, a co-founder and CEO of Lenddo. “What’s new is that we’re now able to measure through massive computing power.”

Moving along from taking out loans to getting jobs, there’s this description of how recruiters work online to perform digital background checks for potential employees. It’s a different set of laws this time that is subject to arbitrage but it’s exactly the same idea:

Non-discrimination laws prohibit employers from asking job applicants certain questions. They’re not supposed to ask about things like age, race, gender, disability, marital, and veteran status. (As you can imagine, sometimes a picture alone can reveal this privileged information. These safeguards against discrimination urge employers to simply not use this knowledge to make hiring decisions.) In addition to protecting people from systemic prejudice, these employment laws intend to shield us from capricious bias and whimsy. While casually snooping, however, a recruiter can’t unsee your Facebook rant on immigration amnesty, the same for your baby bump on Instagram. From profile pics and bios, blog posts and tweets, simple HR reconnaissance can glean tons of off-limits information.

…

Along with forcing recruiters to gaze with eyes wide shut, straddling legal liability and ignorance, invisible employment screens deny American workers the robust protections afforded by the FTC and the Fair Credit Reporting Act. The FCRA ensures that prospective employees are notified before their backgrounds and credit scores are verified. Employees are free to decline the checks, but employers are also free to deny further consideration unless a screening is allowed to take place. What’s important here is that employees must first give consent.

When a report reveals unsavory information about a candidate, and the employer chooses to take what’s called “adverse action,”—like deny a job offer—the employer is required to share the content of the background reports with the candidate. The applicant then has the right to explain or dispute inaccurate and incomplete aspects of the background check. Consent, disclosure, and recourse constitute a straightforward approach to employment screening.

Contrast this citizen-empowering logic with the casual Google search or to the informal, invisible social-media exam. As applicants, we don’t know if employers are looking, we’re not privy to what they see, and we have no way to appeal.

As legal scholars Daniel Solove and Chris Hoofnagle discuss, the amateur Google screens that are now a regular feature of work-life go largely unnoticed. Applicants are simply not called back. And they’ll never know the real reason.

I think the silent failure is the scariest part for me – people who don’t get jobs won’t know why.

Similarly, people denied loans from Lending Club by a secret algorithm don’t know why either. Maybe it’s because I made friends with the wrong person on Facebook? Maybe I should just go ahead and stop being friends with anyone who might put my electronic credit score at risk?

Of course this rant is predicated on the assumption that we think anti-discrimination laws are a good thing. In an ideal world, of course, we wouldn’t need them. But that’s not where we live.

HSBC protest tomorrow at noon with Alternative Banking (#OWS)

I’m helping organize a protest against HSBC with my Alternative Banking group. We’re going to be joined by Everett Stern, an HSBC whistleblower. You can learn more about that guy by reading Matt Taibbi’s Rolling Stones article on him.

Here’s the press release, I hope I see you there!

I don’t want you to be happy

I was giving unwanted advice to my friend the other day, complaining to him about how he’s this absolutely fantastic, wonderful young person – all true – and he’s wasting his time feeling like he’s wasting his time.

Look, he’s obsessed over time. He’s always complaining about being late, or being too slow, or being rushed, and he never thinks he has time to do anything. He’s too old to embark on something.

He’s on tenure track, so that might be part of the problem, but on the other hand he’s gonna get tenure, even he admits that, so not really.

I was telling him to stop worrying about time and just enjoy being awesome. Here I am, quite a few years older, and I’m not at all rushed when it comes to accomplishment. Maybe it’s because I’m a woman and many of my favorite role models are women who change their careers at the age of 75, become potters or writers or poets or what have you. I don’t think I’ll ever need to feel like it’s too late to do something I really want to do. If I’m still alive there’s still time.

“Anyway,” I end my speech, “I’m just saying this because I want you to be happy.”

“Happy?” he says, “please don’t say that. You don’t actually want me to be happy. Come on, you can do better than that.”

And that’s when it hit me. I don’t want him to be happy. I just want him to have better suffering. Instead of suffering about the amount of time he has to do things, which is a self-produced drama, I want him to strive for goals and accomplishments without the noise of crappy I’m-too-late suffering.

I want him to have meaningful suffering, not happiness.

I mean, it depends on what you mean by happiness, but in that conversation he made me realize that wishing happiness on someone is a pretty bland goal. Maybe even an unkind goal.

In fact, it’s the goal I say I wish for my kids when I really hope they’re safe. I’m not so sure “happy” is all that different from “doesn’t get involved in the world too much, stays out of trouble, and is safe”. If you don’t believe me, check out this guy (hat tip Chris Wiggins), whose stated goal is to be happy but whose practice is to ignore all things that interrupt his world view and to make silly lists.

Example from my life. If a friend of mine got his college savings, bought an apartment in Paris, and spent his days combing the catacombs of Paris, I’d want to hang out with that guy. If my son did the same thing, I’d want to convince him not to do it, and to go to college instead. After all, I’d argue, it’s for his own good, he should get an education. I’d tell him I was urging this because I want him to be happy.

Two conclusions.

First, as a parent I’ll strive to spend less time protecting my children from harm and more time letting them seek their own adventures. I want more for them, frankly, than that they’re happy/safe.

Second, I want to start urging my friends to find meaningful suffering. Strive for something and be temporarily miserable when you don’t get it. Hate the world enough to never be satisfied with how shitty things are, love the world enough to stay engaged with it anyway.

College ranking models

Last week Obama began to making threats regarding a new college ranking system and its connection to federal funding. Here’s an excerpt of what he was talking about, from this WSJ article:

The president called for rating colleges before the 2015 school year on measures such as affordability and graduation rates—”metrics like how much debt does the average student leave with, how easy is it to pay off, how many students graduate on time, how well do those graduates do in the workforce,” Mr. Obama told a crowd at the University at Buffalo, the first stop on a two-day bus tour.

Interesting! This means that Obama is wading directly into the field of modeling. He’s probably sick of the standard college ranking system, put out by US News & World Reports. I kind of don’t blame him, since that model is flawed and largely gamed. In fact, I made a case for open sourcing that model recently just so that people would look into it and lose faith in its magical properties.

So I’m with Obama, that model sucks, and it’s high time there are other competing models so that people have more than one thing to think about.

On the other hand, what Obama is focusing on seems narrow. Here’s what he supposedly wants to do with that model (again from the WSJ article):

Once a rating system is in place, Mr. Obama will ask Congress to allocate federal financial aid based on the scores by 2018. Students at top-performing colleges could receive larger federal grants and more affordable student loans. “It is time to stop subsidizing schools that are not producing good results,” he said.

His main goal seems to be “to make college more affordable”.