I don’t want more women at Davos

There was a New York Times article yesterday entitled A Push for Gender Equality at the Davos World Economic Forum, and Beyond. It was about how only 18% of the attendees of the yearly dick-measuring contest called the World Economic Forum – or Davos for the initiated – are women, and how they are planning to force companies to bring more women to improve this embarrassing attendance statistic.

One thing the article didn’t consider is the question of whether it’s actually a good thing that women aren’t at Davos. I think it is; I’m proud that women have better things to do than spend their time in high-security luxury to disingenuously discuss the world’s poor.

Davos is a force of inequality. It brings together dealmakers in finance and technology, and also the TED-talkish Big Idea promoters and “thought leaders,” and it encourages them to mingle and make deals. And while they might discuss the world’s big problems – like increasing inequality itself – I’m pretty sure they try much harder to help themselves than to solve those problems. In any case, I have little faith in their proposed solutions, especially after talking to Bill Easterly on Slate Money last week.

Let’s just cancel Davos altogether, shall we? That will do the world more good than getting more women to attend.

Crank up New York real estate taxes

There are two reasons to own a house. The first one is to live in it. The second is to sell it later at a profit.

These two reasons have led to two different housing markets in New York City. The first one what we might call the affordable housing market, and it simply refers to normal people who need to live somewhere but don’t have extra millions of dollars to spend. The second one is the luxury real estate market of New York, which is exactly for people who have large pots of investment money.

Those two housing markets compete with each other, and lately the luxury market is entirely dominating. This is partly due to the large amount of foreign money being laundered and funneled into real estate. (Update: the U.S. Treasury has said it will look into this, but some people are already claiming it won’t be enough.) It’s also partly due to general global inequality, which produces quite a few millionaires.

Finally, it’s partly due to the bizarre constellation of tax breaks we give new developments, even if only temporarily. It makes holding on to apartments relatively frictionless, even if they are empty, which many of them are. On a permanent basis owners of luxury apartments pay a tiny fraction of the real estate tax that other New Yorkers do relative to the sale price of their apartment (h/t Nathan Newman).

And that’s where we come to the problem. The people who want to live in New York are being shut out by the people who want to own apartment-shaped assets.

If you were a developer, looking for your next building project, you might succumb. Given the expense of land, it makes sense to maximize your profits and build 3- or 4-bedroom apartments that will be snatched up by Russian oligarchs rather than a large number of studios that will actually be lived in. It just makes you more money.

What should we do? Well, we could do nothing. In the long run we might have a city that consists of mostly empty apartments.

Or, we could decide that people should actually live here. In that case we should increase real estate taxes until things change.

Right now we create the exact wrong incentives. First, because non-residents don’t pay city income taxes, and second because we often delay taxes on new apartments and make taxes too low overall. If you think about that, we are actually setting up incentives for the situation we have: empty luxury apartments.

Instead we should make sure that luxury apartments pay more than their fair share of taxes, instead of less, and especially when they’re empty. Don’t worry, the billionaire owners can afford it, and if they can’t, then they can sell it to a mere millionaire who lives in Park Slope.

You see, if an apartment – especially an empty apartment – actually costs the owner a lot of money, they’d sell it, and they’d sell it to a person that would actually live there. That would bring prices down on those assets, because the rich people could simply shift their interest to the fine art market or some other place where holding assets doesn’t cost as much.

Finally, if real estate taxes went up, people might worry that their rent would go up too. But if the market as a whole became a market for normal people, instead of just for rich foreigners, the overall costs would become more reasonable, not less.

The SHSAT matching algorithm isn’t that hard

My 13-year-old took the SHSAT in November, but we haven’t heard the results yet. In fact we’re expecting to wait two more months before we do.

What gives? Is it really that complicated to match kids to test schools?

A bit of background. In New York City, kids write down a list of their preferred public high schools that are not “SHSAT” schools. Separately, if they decide to take the SHSAT, they rank their preferences for those, which fall into a separate category and which include Stuyvesant and Bronx Science. They are promised that they will get into the first school on the list that their SHSAT score allows them to.

I often hear people say that the algorithm to figure out what SHSAT school a given kid gets into is super complicated and that’s why it takes 4 months to find out the results. But yesterday at lunch, my husband and I proved that theory incorrect by coming up with a really dumb way of doing it.

- First, score all the tests. This is the time-consuming part of the process, but I assume it’s automatically done by a machine somewhere in a huge DOE building in Brooklyn that I’ve heard about.

- Next, rank the kids according to score, highest first. Think of it as kids waiting in line at a supermarket check-out line, but in this scenario they just get their school assignment.

- Next, repeat the following step until all the schools are filled: take the first kid in line and give them their highest pick. Before moving on to the next kid, check to see if you just gave away the last possible slot to that particular school. If so, label that school with the score of that kid (it will be the cutoff score) and make everyone still in line erase that school from their list because it’s full and no longer available.

- By construction, every kid gets the top school that their score warranted, so you’re done.

A few notes and one caveat to this:

- Any kid with no schools in their list, either because they didn’t score high enough for the cutoffs or because the schools all filled up before they got to the head of the line, won’t get into an SHSAT school.

- The above algorithm would take very little time to actually run. As in, 5 minutes of computer time once the tests are scored.

- One caveat: I’m pretty sure they need to make sure that two kids with the same exact score and the same preference would both either get in or get out (because think of the lawsuit if not). So the actual way you’d implement the algorithm is when you ask for the next kid in line, you’d also ask for any other kid with the same score and the same top choice to step forward. Then you’d decide whether there’s room for the whole group or not.

So, why the long wait? I’m pretty sure it’s because the other public schools, the ones where there’s no SHSAT exam to get in (but there are myriad other requirements and processes involved, see e.g. page 4 of this document) don’t want people to be notified of their SHSAT placement 4 months before they get their say. It would foster too much unfair competition between the systems.

Finally, I’m guessing the algorithm for matching non-SHSAT schools is actually pretty complicated, which is I think why people keep talking about a “super complex algorithm.” It’s just not associated to the SHSAT.

O’Neil family anthem

I’m working through final edits today, and it’s terribly stressful, so I’m glad I spent last night with my three sons listening to their favorite music.

The most important songs to share with you come from Rob Cantor, who just happens to be incredibly talented. I want to see him live with my kids but so far I haven’t found out about any concerts he’s planning. Here’s my fave Cantor tune (obviously, because I’m an emo):

Next, my 7-year-old’s favorite Cantor tune, Shia LaBeouf:

And my 13-year-old’s favorite, Old Bike:

Just in case you think we only listen to this guy, I wanted to share with you the song that all of us sing regularly, for whatever reason. We make up reasons to sing this song, and it can fairly be called the O’Neil/de Jong family anthem. It’s called First Kiss Today, and made – or constructed anyway – by Songify This. Bonus footage from Biden:

Surveillance and wifi in NYC subways

This morning I heard some news from the Cuomo administration (hat tip Maxine Rockoff).

Namely, we’re set to get mobile tickets in the NYC subways:

In addition, they’re saying we will have wi-fi in the stations, as well as surveillance cameras on all the subways and buses. Oh, and charging stations for USB chargers.

My guess: the surveillance cameras will continue to function long after the USB chargers get filled with gum.

Which Michigan cities are in receivership?

Yesterday at my Occupy meeting we watched a recent Rachel Maddow piece on the suspension of democracy in Michigan:

If it’s too long, the short version is that instead of having elected officials, some specially chosen towns have instead ‘Emergency Managers,’ who do things like save money by pumping in poisonous water.

So, as usual, my group had a bunch of questions, among them: what is the racial make-up of the towns who are in receivership?

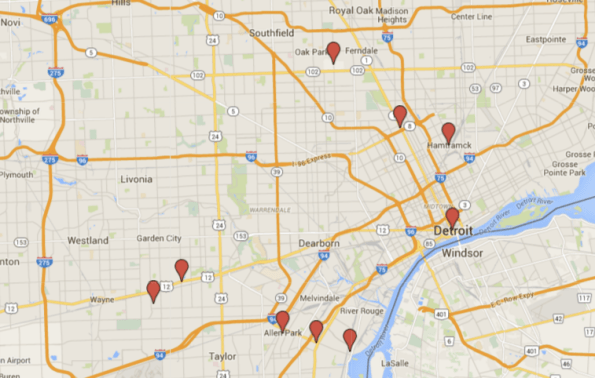

Well first, here’s a list of towns currently under receivership, which I mapped on Google Maps:

You can interact with my map here.

And next I looked at a census map of where black people live in Michigan:

Taken from this website which displays 2010 census data

I also wanted to zoom into the Detroit area:

Taken from the Washington Post website

and compared that to the municipalities under receivership in the area:

Take a closer look here.

Just in case you’re wondering, that teal spot on the left is exactly where the Inkster is. And Wayne County’s government is also in receivership, but it’s a county, not a town.

The economics of weight loss

Tomorrow’s recording of Slate Money will concern New Year’s resolutions. We’re talking about gym memberships and health classes, Fitbits and other “quantified self” devices, and the economics of Weight Watchers and other weight loss industry companies.

I’m in charge of researching the weight loss industry, which was estimated at $64 billion in 2014. That’s huge, but actually it’s dwindling, as people formally diet less often and instead try to informally “eat healthy.”

In fact, Weight Watchers is an old person’s company; the average age is 48, and Oprah’s recent help notwithstanding, younger people are more likely to be interested in quantified self devices which can track calories burned and so on than they are in getting together in person and talking with people about the struggle.

Also, Obamacare doesn’t cover weight programs outside of a doctor’s office, so that has dried up funds as well.

This is good news, because there’s really no evidence that weight loss programs work long-term, but they are expensive. They keep doing studies but they never come out with any positive results beyond 12 months. That’s because they don’t have any evidence.

For example, if I joined Weight Watchers, I’d pay $44.95 per month, although I get refunded if I lost 10 pounds quickly enough. I’d be able to go to meetings two blocks away from my house every Wednesday. The plan will auto-renew and charge my credit card unless I cancel it, which is tantamount to admitting defeat. I’m wondering what the statistics are on people who are paying monthly but no longer attending meetings.

If you want an extreme example of the current dysfunction around dieting, look no further than the show The Biggest Loser, which the Guardian featured recently with the tag line, “It’s a miracle no one has died yet.”

So, given how much money people put into this stuff even now, why are they doing it? After all, if we were expected to pay a doctor to set the bones of our broken leg, but it only worked for a few months before our leg started breaking again, we’d call the doctor a quack and demand our money back. But somehow with diets it’s different. Why?

I have a complicated theory.

The first level is the “I’m an exception” law of human nature, whereby everyone thinks they somehow will prove to be an exception to statistical rules. It’s the same magical reasoning that makes people buy lottery tickets when they know their chances of winning are slim, and they even know their expected value is negative.

The second level is entertainment. This is also taken directly from the lottery mindset; even if you know you’re not winning the lottery, the momentary fantasy of possibly winning is delicious, and you relish it. The cost of that fantasy is a small price to pay for the freedom to believe in this future for one day.

I think the same kind of thing happens when people join diets. They get to fantasize about how great their lives will be once they’re finally thin. And of course the prevalent fat shaming helps this myth, as does the advertising from the diet industry. It’s all about imagining a “new you,” as if you also get a personality transplant along with losing weight.

But there’s something even more seductive about weight loss regimens that lotteries don’t have, namely public support. When someone announces that they’re on a diet, which happens pretty often, everyone around them has been trained to “be supportive” in their endeavor. At the same time, people rarely announce they’ve gone off their diet. So you’ve got asymmetrical dieting attention.

That attention also has a moral flavor to it. Since people are expected to have control over their weight, they are given moral standing when they announce their diet; it is a sign they are finally “taking control.” Never mind that their chances of long-term success are minimal.

The third and final phase, which is the saddest, is guilt. Because we’ve bought in to the idea that people have direct control over their weight, when people end up giving up, they feel personally guilty and end up paying extra money for basically nothing in return.

Of course, no part of this story is all that different from the story of gym memberships or even Fitbit-like device acquisition. Seen together, it’s just a question of what quasi-moralistic self-help fad happens to be popular at any given moment. And there’s tons of money in all of it.

Finishing up Weapons of Math Destruction

Great news, you can now pre-order my book on Amazon. That doesn’t mean it’s completely and utterly finished, but nowadays I’m working on endnote formatting rather than having existential crises about the content. I’m also waiting to see the proposed design of the book’s cover, for which I sent in a couple of screen shots of my python code. And pretty soon I get to talk about stuff like font, which I don’t care about at all.

But here’s the weird part. This means it’s beginning.

You see, when you’ve lived your life as a mathematician and quant, projects are usually wrapped up right around now. You do your research, give talks, and finally write your paper, and then it’s over. I mean, not entirely, because sometimes people read your paper, but actually that mostly doesn’t happen for the published version but instead with the preprint archive. By the time you’ve finished submitting your paper, you’re kind of over your result and you want to move on.

When you do a data science project, a similar thing happens. The bulk of the work happens pre-publishing. Once the model is published, it’s pretty much over for you, and you go on to the next project.

Not so with book publishing. This whole process, as long and as arduous and soul-sucking as it’s been, is just a pre-cursor to the actual event, which is the publication of the book (September 6th of next this year). Then I get to go around talking about this stuff with people for weeks if not months. And although I’m very familiar with the content, the point of writing the book wasn’t simply for me to know the stuff and then move on, it’s for me to spread that message. So it’s also exciting to talk to other people about it.

I also recently got a booking agent, which you can tell if you’ve noticed my new Contact Page. That means that when people invite me to give a talk they’re going to deal with her first, and she’s going to ask for real money (or some other good reason I might want to do it). This might offend some people, especially academics who are used to having people available to donate their time for free, but I’m really glad to have her, given how many talk requests I get on a weekly basis.

Racial identity and video games

Yesterday I stumbled upon an article entitled The Web is not a post-racial utopia, which concerns a videogame called Rust. It explains that when player enters the world of the game, they are “born” naked and alone. The game consists of surviving the wilderness. I’m guessing it’s like a grown-up version of Minecraft in some sense.

In the initial version of the game, all the players were born bald and white. In a later version, race was handed out randomly. And as you can guess, the complaints came pouring in after the change, as well as a marked increase in racially hostile language.

This is all while blacks and Hispanics play more videogames than whites. They were not complaining about being cast as a white man in the initial version, because it’s so common. Videogame designers are almost all white guys.

I’ll paraphrase from a great interview with one of the newest Star Wars heros John Boyega when I say, I’m pretty sure there wouldn’t have been any complaints if everybody were born a randomly colored alien. White people are okay with being cast as a green alien avatar, but no way they’re going to be cast as a black man. WTF, white people?

Of course, not everyone’s complaining. In fact the reactions are interesting although extreme. They’re thinking of setting up analytics to track the reactions. They’re also thinking of assigning gender and other differences randomly to avatars. And by the way, it looks like they’ve recently been attacked by hackers.

For what it’s worth, I’d love to see men in video games dealing with getting their period. Actually, that’s a great idea. Why not have that as part of the 7th grade ‘Health and Sexuality’ curriculum for both boys and girls? Those who advance to the next level can experience being pregnant and suffering sciatica. Or maybe even hot flashes and menopause, why not?

Parenting is really a thing

I’d been skating along with the parenting thing for quite a while. I have three sons, the oldest of whom is 15 and the youngest 7. It’s been a blizzard of pancakes and lost teeth, and almost nothing has really fazed me.

Until about 3 months ago, when my little guy broke his leg. The pain was excruciating, and traumatic for both him and anyone near him, even after his cast was set. He was in a wheelchair for 7 weeks all told, which was probably too long, but we had conflicting advice and went with what we were told by the doctor.

Then, finally, the cast came off three weeks ago. I thought this episode was finally over. But my son refused to walk.

It was more important for him to go to school than anything, so back he went into his wheelchair for the next few days. I figured he’d get back to walking over the weekend. He didn’t. The doctor who took off the cast had dismissed his fear, saying he’d be walking “by the afternoon.” Another doctor told us there was “nothing physically wrong with him.” But after a week of begging him to try, and threatening to take away his computer, we were all a mess.

Then, when my husband was out of town, I got even more anxious. I made the mistake of taking him to see a pediatrician who I don’t trust, but it was right before Christmas and I was desperate. Mistake. The guy told me he had “hysterical paralysis” and gave me the number of a psychiatrist who charges $1500 per hour and doesn’t take insurance.

Luckily, friends of mine suggested physical therapy. I found an amazing pediatric physical therapist who came to our house and convinced him to try stepping while leaning on the table for support. Then came days and days of grueling and stressful practice. We didn’t see much progress, but at least it was some exercise.

Finally, I decided it was all too intense and stressful. I drove him and me to a hotel near my favorite yarn store in Massachusetts – a yearly tradition but it’s usually the whole family – and we just went swimming for hours and hours in the hotel pool. I could see how joyous he became in the water, where there was no sense of gravity and he was once again fully able-bodied. I had to drag him out of the pool every time. I think he would have slept in it if I’d let him.

Yesterday morning we checked out of the hotel. We had stopped talking days before about when he’d start walking, we’d just enjoyed each other’s company and snuggled every chance we got. On the way out of the elevator and on to the check-out desk, my son said to me, “I’m just going to walk now.” And he did.

So, parenting is really a thing. The hardest part has been learning to trust my kids to get through difficult things even when I can’t help them directly. I knew that about homework already, but from now on I guess it just gets bigger and harder.

We could use some tools of social control to use on police

You may have noticed I’ve not been writing much recently. That’s because I turned in the latest draft of my book, and then I promptly took a short vacation from writing. In fact I ensconced myself in a ridiculous crochet project:

which is supposed to be a physical manifestation of this picture proof:

which I discussed a few months ago.

Anyhoo, I’ve gotten to thinking about the theme of my book, which is, more or less, how black box algorithms have become tools of social control. I have a bunch of examples in my book, but two of the biggies are the Value-Added Model, which is used against teachers, and predictive policing models, which are used by the police against civilians (usually, you guessed it, young men of color).

That makes me think – what’s missing here? Why haven’t we built, for example, models which assess police?

If you looked for it, the closes you’d come might be the CompStat data-driven policing models that measure a cop by how many arrests and tickets he’s made. Basically the genesis of the quota system.

But of course that’s only one side of it, and the less interesting one; how about how many people the policeman has shot or injured? As far as I know, that data isn’t analyzed, if it’s even formally collected.

That’s not to say I want a terrible, unaccountable model that unfairly judges police like the one we have for teachers. But I do think our country has got its priorities backwards when we put so much focus and money towards getting rid of the worst teachers but we do very little towards getting rid of the worst cops.

The example I have in mind is, of course, the police that shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice and didn’t get indicted. The prosecutor was quoted as saying, “We don’t second-guess police officers.” I maintain that we should do exactly that. We should collect and analyze data around police actions as long as children are getting killed.

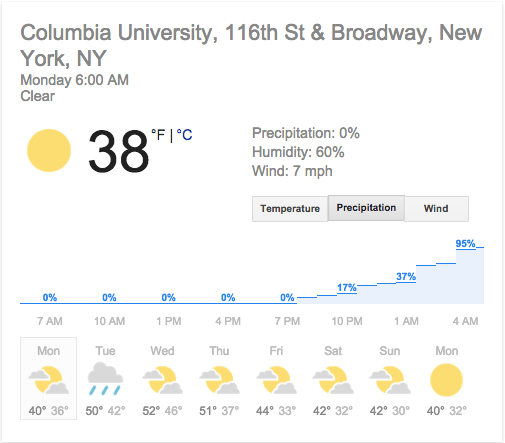

Forecasting precipitation

What does it means when you’re given a precipitation forecast? And how do you know if it’s accurate? What does it mean when you see that there’s a 37% chance of rain?

Well, there are two input variables you have to keep in mind: first, the geographic location – where you’re looking for a forecast, and second, the time window you’re looking at.

For simplicity let’s fix a specific spot – say 116th and Broadway – and let’s also fix a specific one hour time window, say 1am-2am.

Now we can ask again, how would we interpret a “37% chance of rain” for this location during this time? And when do we decide our forecast is good? It’s trickier than you might think.

***

Let’s first think about interpretation. Hopefully what that phrase means is something like, 37 out of 100 times, with these exact conditions, you’ll see a non-zero, measurable amount of rain or other precipitation during an hour. So far so good.

Of course, we only have exactly one of these exact hours. So we cannot directly test the forecast with that one hour. Instead, we should collect a lot of data on the forecast. Start by building 101 bins, labeled from 0 to 100, and throw each forecasted hour into the appropriate bin, along with a record of the actual precipitation outcome.

So if it actually rains between 1am and 2am at 116th and Columbia, I’d throw this record into the “37” bin, along with a note that said “YES IT RAINED.” I’d short hand this note by attaching a “1” to the record, which stands for “100% chance of rain because it actually rained.” I’d attach a “0” to each hour where it didn’t rain.

I’d do this for every single hour of every single day and at every single location as well, of course not into the “37” bin but into the bin with the forecasted number, along with the note of whether rain came. I’d do this for 100 years, or at least 1, and by the end of it I’d presumably have a lot of data in each bin.

So for the “0” bin I’d have many many hours where there wasn’t supposed to be rain. Was there sometimes rain? Yeah, probably. So my “0” bin would have a bunch of records with “0” labels and a few with “1” labels. Each time a “1” record made its way into the “0” bin, it would represent a failure of the model. I’d need to count such a failure against the model somehow.

But then again, what about the “37” bin? Well I’d want to know, for all the hours forecasted to have a 37% chance of rain, how often it actually happened. If I ended up with 100 examples, I’d hope that 37 our of the 100 examples ended up with rain. If it actually happened 50 times out of 100, I’d be disappointed – another failure of the model. I’d need to count this against the model.

Of course to be more careful I’d rather have 100,000 examples accumulated in bin “37” and see 50,000 of those hours actually had rain. With that data I’d be fairly certain this forecasting engine is inaccurate.

Or, if 37,003 of those examples actually saw rain, then I’d be extremely pleased. I’d be happy to trust this model when it says 37% chance of rain. But then again, it might still be kind of inaccurate when it comes to the bin labeled “72”.

We’ve worked so hard to interpret the forecast that we’re pretty close to determining if it’s accurate. Let’s go ahead and finish the job.

***

Let’s take a quick reality check first though. Since I’ve already decided to fix on a specific location, namely at 116th and Broadway, the ideal forecast would always just be 1 or 0: it’s either going to rain or it’s not.

In other words, we have the ideal forecast to measure all other forecasts against. Let’s call that God’s forecast, or if you’re an atheist like me, call it “mother nature’s forecast,” or MNF for short. If you tried to test MNF, you’d set up your 101 bins but you’d only ever use 2 of them. And they’d always be right.

***

OK, but this is the real world, and forecasting weather is hard, especially when it’s a day or two in advance, so let’s try instead to compare two forecasts head to head. Which one is better, Google or Dark Sky?

I’d want a way to assign scores to each of them and choose the better precipitation model. Here’s how I’d do it.

First, I’d do the bin thing for each of them, over the same time period. Let’s say I’m still obsessed with my spot, 116th and Broadway, and I’ve fixed a year or two of hourly forecasts to compare the two models.

Here’s my method. Instead of rewarding a model for accuracy, I’m going to penalize it for inaccuracy. Specifically, I’ll assign it a squared error term for each time it forecast wrong.

To see how that plays out, let’s look at the “37” bin for each model. As we mentioned above, any time the model forecasts 37% chance of rain, it’s wrong. It either rains, in which case it’s off by 1.00-0.37 = 0.63, or it doesn’t rain, in which case the error term is 0.37. I will assign it the square of those terms as penalty for its wrongness.

***

How did I come up with the square of the error term? Why is it a good choice? For one, it has the following magical property: it will be minimized when the label “37” is the most accurate.

In other words, if we fix for a moment the records that end up in the “37” bin, the sum of the squared error terms will be the smallest when the true proportion of “1”s to “0”s in that bin is 37%.

Said another way, if we have 100,000 records in the “37” bin, and actually 50,000 of them correspond to rainy hours, then the sum of all the squared error terms ends up much bigger than if only 37,000 of them turned into rain. So that’s a way of penalizing a model for inaccuracy.

To be more precise, if our true chances of rain is but our bin is actually labeled

then the average penalty term, assuming we’ve collected enough data to ignore measurement error, will be

or

The crucial fact is that is always positive, so the above penalty term will be minimized when

is zero, or in other words when the label of the bin perfectly corresponds to the actual chance of rain.

Moreover, other ways of penalizing a specific record in the “37” bin, say by summing up the absolute value of the error term, don’t have this property.

***

The above has nothing to do with “bin 37,” of course. I could have chosen any bin. To compare two forecasting models, then, we add up all the squared error terms of all the forecasts over a fixed time period.

Note that any model that ever spits out “37” is going to get some error no matter what. Or in other words, a model that wants to be closer to MNF would minimize the number of forecasts to put into the “37” bin and try hard to put forecasts into either the “0” bin or the “1” bin, assuming of course that they had confidence in the forecast.

Actually, the worst of all bins – the one the forecast accumulates the most penalty for – is the “50” bin. Putting an hourly forecast into the “50” bin is like giving up – you’re going to get a big penalty no matter what, because again, it’s either going to rain or it isn’t. Said another way, the above error term is maximized at

.

But the beauty of the square error penalty is that it also rewards certainty. Another way of saying this is that, if I am a forecast and I want to improve my score, I can either:

- make sure the forecasts in each bin are as accurate as possible, or

- try to get some of the forecasts in each bin out of their current bins and closer to either 0 or 1.

Either way their total sum of square error will go down.

I’m dwelling on this because there’s a forecast out there that we want to make sure is deeply shamed by any self-respecting scoring system. Namely, the forecast that says there’s a n% chance of rain for every hour of every day, where n is chosen to be the average hourly chance of rain. This is a super dumb forecast, and we want to make sure it doesn’t score as well as God or mother nature, and thankfully it doesn’t (even though it’s perfectly accurate within each bin, and it only uses one bin).

Then again, it would be good to make sure Google scores better than the super dumb forecast, which I’d be happy to do if I could actually get my hands on this data.

***

One last thing. This entire conversation assumed that the geographic location is fixed at 116th and Broadway. In general, forecasts are made over some larger land mass, and that fact affects the precipitation forecast. Specifically, if there’s an 80% chance that precipitation will occur over half the land mass and a 0% chance it will occur over the other half for a specific time window, the forecast will read 40%. This is something like the chance that an average person in that land mass will experience precipitation, assuming they don’t move and that people are equidistributed over the land mass.

Then again with the proliferation of apps that intend to give forecasts for pinpointed locations, this old-fashioned forecasting method will probably be gone soon.

My favorite scams of 2015

Am I the only person who’s noticed just a whole lot of scams recently? I blame it on our global supply chain that’s entirely opaque and impenetrable to the outsider. We have no idea how things are made, what they’re made with, or how the end results get shipped around the world.

Seriously, anything goes. And that’s probably not going to change. The question is, will scams proliferate, or will we figure out an authentication system?

Who knows. For now, let’s just remind ourselves of a few recent examples (and please provide more in the comments if you think of any!).

- VW’s cheating emissions scandal, obviously. That’s the biggest scam that came out this year, and it happened to one of the biggest car companies in the world. We’re still learning how it went down, but clearly lots of people were in on it. What’s amazing to me is that no whistleblower did anything; we learned about it from road tests by an external group. Good for them.

- Fake artisanal chocolate from Brooklyn. The Amish-looking hipsters just melted chocolate they bought. I mean, the actual story is a bit more complicated and you should read it, but it just goes to show you how much marketing plays a part in this stuff. But expert chocolate lovers could tell the difference, which is kind of nice to know.

- Fake bamboo products at Bed, Bugs, & Beyond. I call it that because whenever one of my friends gets bedbugs (it happens periodically in NYC) I go with them to B, B & B for new sheets and pillows. It’s fun. Anyhoo, they were pretending to sell bamboo products but it was actually made from rayon. And before you tell me that rayon is made from plant cellulose, which it is, let me explain that the chemical process that turns plants into cellulose (called extruding) is way more involved and harmful to the environment than simply grabbing bamboo fibers. That’s why people pay more for bamboo products, because they think they’re having less environmental impact.

- We eat horsemeat all the fucking time, including in 2015. This is a recurring story (I’m looking at you, Ikea) but yes, it also happened in 2015.

- And last but not least, my favorite scam of 2015, a yarn distributor called Trendsetter Yarns was discovered to be selling Mimi, a yarn from Lotus Yarns in China, which was labeled as “100% mink” when it was in fact an angora mix with – and this is the most outrageous part – 17% nylon fibers mixed in!!! As you can imagine, the fiber community was thrown into a tizzy when this came out; we yarn snobs turn up our noses at nylon. The story is that a woman who is allergic to angora, and who had bought the “100% mink” yarn specifically so that she’d have no reaction, did, and got suspicious, and sent it to a lab. Bingo, baby.

This skein might look 100% mink, but it’s not.

Star Wars Christmas Special

Look, I don’t smoke pot. I’m allergic to it or something, it’s not a principle or anything. But sometimes I wish I did, because sometimes I find an activity that’s so perfect for the state of being high that I am deeply jealous of the people who can achieve it.

That happened yesterday, when my teenagers introduced me to the Star Wars Christmas Special, which is a truly extraordinary feature length movie, and is really a perfect stoner flick.

I’m really not giving anything away by telling you that there’s a lot of scenes involving Chewbacca’s family, hoping he makes it home in time for “Life Day.” Each of those scenes is inexplicably long and devoid of subtitles.

In fact, it’s really not a stretch to say that every scene in the entire movie is inexplicably long. But that’s perfect for high folks, who are known to drive at 15 miles an hour on the highway and worry they’re speeding.

For those of you who are not high: I suggest you skip this one. I watched it because I’m a huge Star Wars nerd, but even I couldn’t remember why while I was doing it, except that I like hanging out with teenagers rolling on the rug in laughter because it’s so bad it’s good.

According to my kids, George Lucas himself said about this film that if he “had enough time, he’d track down every copy of this film and destroy it.” You have been warned.

Weapons of Math Destruction to be an audiobook

It’s been an intense week, with just a ton of editing on my book, Weapons of Math Destruction: how big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. I’m hopefully very close to final draft. Please keep your fingers crossed along with me that that is true. Obviously I will send an update when I’ve gotten the final word.

What’s cool about this phase is, first of all it seems real, and countable, like you can feel the progress happening, whereas so many other moments seemed completely lost in time, swallowed up by a very loud hum of uncertainty. Was this line of research going to lead anywhere? Will this person I’m interviewing say anything I don’t already know?

Now, at least, I know there’s a book here. And it’s nice to be reminded of all the stuff that’s gone into it, as I read through so many chapters at a time to make sure they work together.

Probably the best part, though, is just how close I am to finishing. It’s been a really big, long project. I likely wouldn’t have taken it on at all if I’d actually known how big and how long, and how uncertain I’d be, so often, that it would end up being a book. So, I guess, here’s to running into things with almost pure ignorance!

Well, yesterday I got some great news. WMD, which is what I call my book for short, since its title is so very very long, is going to be made into an audiobook by the publisher, Random House.

Obviously I’m psyched, and moreover I’m volunteering to do the reading. In this final phase I’ve gotten really into how the book reads out loud, and in fact I’ve enlisted a bunch of my friends (thanks, Laura, Matt, Karen, Maki, Becky, Julie, Mel, Sam, and Aaron!) to read various chapters to me out loud and send me the mp4 files. It’s been a blast hearing them.

Also, I think books are better when the author reads them, right? But what do I know? I’m not in charge. I can only hope they pick me.

Just to stack the decks a wee bit, please leave a comment below with your vote, especially if you’ve ever listened to my Slate Money podcast and can comment on how my voice sounds. Feel free to make copious use of the word “honey-toned.”

This is happening, people! Fuck yes!

Notes on the Oxford IUT workshop by Brian Conrad

Brian Conrad is a math professor at Stanford and was one of the participants at the Oxford workshop on Mochizuki’s work on the ABC Conjecture. He is an expert in arithmetic geometry, a subfield of number theory which provides geometric formulations of the ABC Conjecture (the viewpoint studied in Mochizuki’s work).

Since he was asked by a variety of people for his thoughts about the workshop, Brian wrote the following summary. He hopes that a non-specialist may also learn something from these notes concerning the present situation. Forthcoming articles in Nature and Quanta on the workshop will be addressed at the general public. This writeup has the following structure:

- Background

- What has delayed wider understanding of the ideas?

- What is Inter-universal Teichmuller Theory (IUTT = IUT)?

- What happened at the conference?

- Audience frustration

- Concluding thoughts

- Technical appendix

1. Background

The ABC Conjecture is one of the outstanding conjectures in number theory, even though it was formulated only approximately 30 years ago. It admits several equivalent formulations, some of which lead to striking finiteness theorems and other results in number theory and others of which provide a robust structural framework to try to prove it. The conjecture concerns a concrete inequality relating prime factors of a pair of positive whole numbers (A and B) and their sum (C) to the actual magnitudes of the two integers and their sum. It has a natural generalization to larger number systems (called “number fields”) that arise throughout number theory.

The precise statement of the conjecture and discussion of some of its consequences are explained here in the setting of ordinary whole numbers, and some of the important applications are given there as well. The interaction of multiplicative and additive properties of whole numbers as in the statement of the ABC Conjecture is a rather delicate matter (e.g., if p is a prime one cannot say anything nontrivial about the prime factorization of p+12 in general). This conjectural inequality involves an auxiliary constant which provides a degree of uniform control that gives the conjecture its power to have striking consequences in many settings. Further consequences are listed here.

It is the wealth of consequences, many never expected when the conjecture was first formulated, that give the conjecture its significance. (For much work on this problem and its consequences, it is essential to work with the generalized version over number fields.)

It was known since around the time when the ABC Conjecture was first introduced in the mid-1980’s that it has deep links to — and even sometimes equivalences with — other outstanding problems such as an effective solution to the Mordell Conjecture (explicitly bounding the numerators and denominators of the coordinates of any possible rational point on a “higher-genus” algebraic curve, much harder than merely bounding the number of possible such points; the Mordell Conjecture asserting the mere finiteness of the set of such points was proved by Faltings in the early 1980’s and earned him a Fields Medal). To get explicit bounds so as to obtain an effective solution to the Mordell Conjecture, one would need explicit constants to emerge in the ABC inequality.

An alternative formulation of the conjecture involves “elliptic curves”, a class of curves defined by a degree-3 equation in 2 variables that arise in many problems in number theory (including most spectacularly Fermat’s Last Theorem). Lucien Szpiro formulated a conjectural inequality (called Szpiro’s Conjecture) relating some numerical invariants of elliptic curves, and sometime after the ABC Conjecture was introduced by David Masser and Joseph Oesterle it was realized that for the generalized formulations over arbitrary number fields, the ABC Conjecture is equivalent to Szpiro’s Conjecture (shown by using a special class of elliptic curves called “Frey curves” that also arise in establishing the link between Fermat’s Last Theorem and elliptic curves).

It had been known for many years that Shinichi Mochizuki, a brilliant mathematician working at the Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences (RIMS) in Kyoto since shortly after getting his PhD under Faltings at Princeton in 1992, had been quietly working on this problem by himself as a long-term goal, making gradual progress with a variety of deep techniques within his area of expertise (arithmetic geometry, and more specifically anabelian geometry). Just as with the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, to make progress on the conjecture one doesn’t work directly with the initial conjectural relation among numbers. Instead, the problem is recast in terms of sophisticated constructions in arithmetic geometry so as to be able to access more powerful tools and operations that cannot be described in terms of the initial numerical data. Mochizuki’s aim was to settle Szpiro’s Conjecture.

In August 2012, Mochizuki announced a solution using what he called Inter-Universal Teichmuller Theory; he released several long preprints culminating in the proof of the conjecture. Mochizuki is a remarkable (and very careful) mathematician, and his approach to the ABC Conjecture (through Szpiro’s Conjecture for elliptic curves) is based on much of his own previous deep work that involves an elaborate tapestry of geometric and group-theoretic constructions from an area of mathematics called anabelian geometry. He deserves much respect for having devoted substantial effort over such an extended period of time towards developing and applying tools to attack this problem.

The method as currently formulated by Mochizuki does not yield explicit constants, so it cannot be used to establish an effective proof of the Mordell Conjecture. But if correct it would nonetheless be a tremendous achievement, settling many difficult open problems, and would yield a new proof of the Mordell Conjecture (as shown long ago by Noam Elkies).

Very quickly, the experts realized that the evaluation of the work was going to present exceptional difficulties. The manner in which the papers culminating in the main result has been written, including a tremendous amount of unfamiliar terminology and notation and rapid-fire definitions without supporting examples nearby in the text, has made it very hard for many with extensive background in arithmetic geometry to get a sense of progress when trying to work through the material. There are a large number of side remarks in the manuscripts, addressing analogies and motivation, but to most readers the significance of the remarks and the relevance of the analogies has been difficult to appreciate at first sight. As a consequence, paradoxically many readers wound up quickly feeling discouraged or confused despite the inclusion of much more discussion of “motivation” than in typical research papers. In addition to the difficulties with navigating the written work, the author preferred not to travel and give lectures on it, though he has been very receptive to questions sent to him via email and to speaking with visitors to RIMS.

To this day, many challenges remain concerning wider dissemination and evaluation of his ideas building on anabelian geometry to deduce the ABC Conjecture. With the passage of much time, the general sense of discouragement among many in the arithmetic geometry community was bringing matters to a standstill. The circumstances are described here.

Although three years have passed since the original announcement, it isn’t the case that many arithmetic geometers have been working on it throughout the whole time. Rather, many tried early on but got quickly discouraged (due in part to the density of very new notation, terminology, and concepts). There have been some surveys written, but essentially everyone I have spoken with has found those to be as difficult to parse for illumination as the original papers. (I have met some who found some surveys to be illuminating, but most have not.)

The Clay Mathematics Institute and the Mathematical Institute at Oxford contributed an important step by hosting a workshop last week at Oxford University on Mochizuki’s work, inviting experts from across many facets of arithmetic geometry relevant to the ABC Conjecture (but not themselves invested in Inter-Universal Teichmuller Theory) to try to achieve as a larger group some progress in recognizing parts of the big picture that individuals were unable or too discouraged to achieve on their own. The organizers put in a tremendous amount of effort, and (together with CMI staff) are to be commended for putting it all together. It was challenging to find enough speakers since many senior people were reluctant to give talks and for most speakers many relevant topics in Mochizuki’s work (e.g., Frobenioids and the etale theta function) were entirely new territory. Many speakers understandably often had little sense of how the pieces would finally fit into the overall story. One hope was that by combining many individual efforts a greater collective understanding could be achieved.

I attended the workshop, and among those attending were leading experts in arithmetic or anabelian geometry such as Alexander Beilinson, Gerd Faltings, Kiran Kedlaya, Minhyong Kim, Laurent Lafforgue, Florian Pop, Jakob Stix, Andrew Wiles, and Shou-Wu Zhang. The complete list of participants is given here.

It was not the purpose of the workshop to evaluate the correctness of the proof. The aim as I (and many other participants) understood it was to help participants from across many parts of arithmetic geometry to become more familiar with some key ideas involved in the overall work so as to (among other things) reduce the sense of discouragement many have experienced when trying to dig into the material.

The work of Mochizuki involves the use of deep ideas to construct and study novel tools fitting entirely within mainstream algebraic geometry that give a new angle to attacking the problem. But evaluating the correctness of a difficult proof in mathematics involves many layers of understanding, the first of which is a clear identification of some striking new ideas and roughly how they are up to the task of proving the asserted result. The lack of that identification in the present circumstances, at least to the satisfaction of many experts in arithmetic geometry, lies at the heart of the difficulties that still persist in the wider understanding of what is going on in the main papers. The workshop provided definite progress in that direction, and in that respect was a valuable activity.

The workshop did not provide the “aha!” moment that many were hoping would take place. I am glad that I attended the Oxford workshop, despite serious frustrations which arose towards the end. Many who attended now have a clearer sense of some ingredients and what some key issues are, but nobody acquired expertise in Inter-universal Teichmuller Theory as a consequence of attending (nor was it the purpose, in my opinion). In view of the rich interplay of ideas and intermediate results that were presented at the workshop, including how much of Mochizuki’s own past work enters into it in many aspects, as well as his own track record for being a careful and powerful mathematician, this work deserves to be taken very seriously.

References below to opinions and expectations of “the audience” are based on conversations with many participants who have expertise in arithmetic geometry (but generally not with Inter-universal Teichmuller Theory). As far as I know, we were all on the same wavelength for expectations and impressions about how things evolved during the week. Ultimately any inaccuracy in what is written below is entirely my responsibility. I welcome corrections or clarification, to be made through comments on this website for the sake of efficiency.

2. What has delayed wider understanding of the ideas?

One source of difficulties in wider dissemination of the main ideas appears to be the fact that prior work on which it depends was written over a period of many years, during much of which it was not known which parts would finally be needed just to understand the proof of the main result. There has not been a significant “clean-up” to give a more streamlined pathway into the work with streamlined terminology/notation. This needs to (eventually) happen.

Mochizuki aims to prove Szpiro’s conjecture for all elliptic curves over number fields, with a constant that depends only on the degree of the number field (and on the choice of epsilon in the statement). The deductions from that to more concrete consequences (such as the ABC Conjecture and hence many finiteness results such as: the Mordell Conjecture, Siegel’s theorem on integral points of affine curves, and the finiteness of the set of elliptic curves over a fixed number field with good reduction outside a fixed finite set of places) have been known for decades and do not play any direct role in his arguments. In particular, one cannot get any insight into Mochizuki’s methods by trying to “test them out” in the context of such concrete consequences, as his arguments are taking place entirely in the setting of Szpiro’s Conjecture (where those concrete consequences have no direct relevance).

Moreover, his methods require the elliptic curve in question to satisfy certain special global and local properties (such as having split 30-torsion and split multiplicative reduction at all bad places) which are generally not satisfied by Frey curves but are attained over an extension of the ground field of controlled degree. From those special cases he has a separate short clever argument to deduce the general case from such special cases (over general number fields!) at the cost of ineffective constants. Thus, one cannot directly run his methods over a small ground field such as the rational numbers; the original case for ordinary integers is inferred from results over number fields of rather large (but controlled) degree.

Sometimes the extensive back-referencing to earlier papers also on generally unfamiliar topics (such as Frobenioids and anabelioids) has created a sense of infinite regress, due to the large number of totally novel concepts to be absorbed, and this has had a discouraging effect since the writing is often presented from the general to the specific (which may be fine for logic but not always for learning entirely new concepts). For example, if one tries to understand Mochizuki’s crucial notion of Frobenioid (the word is a hybrid of “Frobenius” and “monoid”), it turns out that much of the motivation comes from his earlier work in Hodge-Arakelov theory of elliptic curves, and that leads to two conundrums of psychological (rather than mathematical) nature:

- Hodge-Arakelov theory is not used in the end (it was the basis for Mochizuki’s original aim to create an arithmetic version of Kodaira-Spencer theory, inspired by the function field case, but that approach did not work out). How much (if any) time should one invest to learn a non-trivial theory for motivational purposes when it will ultimately play no direct role in the final arguments?

- Most of the general theory of Frobenioids (in two prior papers of Mochizuki) isn’t used in the end either (he only needs some special cases), but someone trying on their own to learn the material may not realize this and so may get very discouraged by the (mistaken) impression that they have to digest that general theory. There is a short note on Mochizuki’s webpage which points out how little of that theory is ultimately needed, but someone working on their own may not be aware of that note. Even if one does find that note and looks at just the specific parts of those earlier papers which discuss the limited context that is required, one see in there ample use of notation, terminology, and results from earlier parts of the work. That may create a sense of dread (even if misplaced) that to understand enough about the special cases one has to dive back into the earlier heavier generalities after all, and that can feel discouraging.

An analogy that comes to mind is learning Grothendieck’s theory of etale cohomology. Nowadays there are several good books on the topic which develop it from scratch (more-or-less) in an efficient and direct manner, proving many of the key theorems. The original exposition by Grothendieck in his multi-volume SGA4 books involved first developing hundreds of pages of the very abstract general theory of topoi that was intended to be a foundation for all manner of future possible generalizations (as did occur later), but that heavy generality is entirely unnecessary if one has just the aim to learn etale cohomology (even for arbitrary schemes).

3. What is Inter-universal Teichmuller Theory (IUT)?

I will build up to my impression of an approximate definition of IUT in stages. As motivation, the method of Mochizuki to settle Szpiro’s Conjecture (and hence ABC) is to encode the key arithmetic invariants of elliptic curves in that conjecture in terms of “symmetry” alone, without direct reference to elliptic curves. One aims to do the encoding in terms of group-theoretic data given by (arithmetic) fundamental groups of specific associated geometric objects that were the focus of Grothendieck’s anabelian conjectures on which Mochizuki had proved remarkable results earlier (going far beyond anything Grothendieck had dared to conjecture). The encoding mechanism is addressed in the appendix; it involves a lot of serious arguments in algebraic and non-archimedean geometry of an entirely conventional nature (using p-adic theta functions, line bundles, Kummer maps, and a Heisenberg-type subquotient of a fundamental group).

Mochizuki’s strategy seems to be that by recasting the entire problem for Szpiro’s Conjecture in terms of purely group-theoretic and “discrete” notions (i.e., freeing oneself from the specific context of algebro-geometric objects, and passing to structures tied up with group theory and category theory), one acquires the ability to apply new operations with no direct geometric interpretation. This is meant to lead to conclusions that cannot be perceived in terms of the original geometric framework.

To give a loose analogy, in Wiles’ solution of Fermat’s Last Theorem one hardly ever works directly with the Fermat equation, or even with the elliptic curve in terms of which Frey encoded a hypothetical counterexample. Instead, Wiles recast the problem in terms of a broader framework with deformation theory of Galois representations, opening the door to applying techniques and operations (from commutative algebra and Galois cohomology) which cannot be expressed directly in terms of elliptic curves. An analogy of more relevance to Mochizuki’s work is the fact that (in contrast with number fields) absolute Galois groups of p-adic fields admit (topological) automorphisms that do not arise from field-theoretic automorphisms, so replacing a field with its absolute Galois group gives rise to a new phenomenon (“exotic” automorphisms) that has no simple description in the language of fields.

To be more specific, the key new framework introduced by Mochizuki, called the theory of Frobenioids, is a hybrid of group-theoretic and sheaf-theoretic data that achieves a limited notion of the old dream of a “Frobenius morphism” for algebro-geometric structures in characteristic 0. The inspiration for how this is done apparently comes from Mochizuki’s earlier work on p-adic Teichmuller theory (hence the “Teichmuller” in “IUT”). To various geometric objects Mochizuki associates a “Frobenioid”, and then after some time he sets aside the original geometric setting and does work entirely in the context of Frobenioids. Coming back to analogues in the proof of FLT, Wiles threw away an elliptic curve after extracting from it a Galois representation and then worked throughout with Galois representations via notions which have no meaning in terms of the original elliptic curve.

The presence of structure akin to Frobenius morphisms and other operations of “non-geometric origin” with Frobenioids is somehow essential to getting non-trivial information from the encoding of arithmetic invariants of elliptic curves in terms of Frobenioids in a way I do not understand and was not clearly addressed at the Oxford workshop, though it seems to have been buried somewhere in the lectures of the final 2 days; to understand this point seems to be an essential step in recognizing where there is some deep contact between geometry and number theory in the method.

So in summary, IUT is, at least to first approximation, the study of operations on and refined constructions with Frobenioids in a manner that goes beyond what we can obtain from geometry yet can yield interesting consequences when applied to Frobenioid-theoretic encodings of number-theoretic invariants of elliptic curves. The “IU” part of “IUT” is of a more technical nature that appears to be irrelevant for the proof of Szpiro’s conjecture.

The upshot is that, as happens so often in work on difficult mathematical problems, one broadens the scope of the problem in order to get structure that is not easily expressible in terms of the original concrete setting. This can seem like a gamble, as the generalized problem/context could possibly break down even when the thing one wants to prove is true; e.g., in Wiles’ proof of FLT this arose via his aim to prove an isomorphism between a deformation ring and a Hecke ring, which was much stronger than needed for the desired result yet was also an essential extra generality for the success of the technique originally employed. (Later improvements of Wiles’ method had to get around this issue, strengthening the technique to succeed without proving a result quite as strong as an isomorphism but still sufficient for the desired final number-theoretic conclusion.)

One difference in format between the nature of Mochizuki’s approach to the Szpiro Conjecture and Wiles’ proof of FLT is that the latter gave striking partial results even if one limited it to initial special cases – say elliptic curves of prime discriminant – whereas the IUT method does not appear to admit special cases with which one might get a weaker but still interesting inequality by using less sophisticated tools (and for very conventional reasons it seems to be impossible to “look under the hood” at IUT by thinking in terms of the concrete consequences of the ABC Conjecture). Mochizuki was asked about precisely this issue during the first Skype session at the Oxford meeting and he said he isn’t aware of any such possibility, adding that his approach seems to be “all or nothing”: it gives the right inequality in a natural way, and by weakening the method it doesn’t seem to simply yield a weaker interesting inequality but rather doesn’t give anything.

Let us next turn to the meaning of “inter-universal.” There has been some attention given to Mochizuki’s discussion of “universes” in his work on IUT, suggesting that his proof of ABC (if correct) may rely in an essential way on the subtle set-theoretic issues surrounding large cardinals and Grothendieck’s axiom of universes, or entail needing a new foundation for mathematics. I will now explain why I believe this is wrong (but that the reason for Mochizuki’s considerations are nonetheless relevant for certain kinds of generalities).

The reason that Mochizuki gets involved with universes appears to be due to trying to formulate a completely general context for overcoming certain very thorny expository issues which underlie important parts of his work (roughly speaking: precisely what does one mean by a “reconstruction theorem” for geometric or field-theoretic data from a given profinite group, in a manner well-suited to making quantifiable estimates?) He has good reasons to want to do this, but a very general context seems not to be necessary if one takes the approach of understanding his proofs along the way (i.e., understanding all the steps!) and just aiming to develop enough for the proof of Szpiro’s Conjecture.

Grothendieck introduced universes in order to set up a rigorous theory of general topoi as a prelude to the development of etale cohomology in SGA4. But anyone who understands the proofs of the central theorems in etale cohomology knows very well that for the purposes of developing that subject the concept of “universe” is irrelevant. This is not a matter of allowing unrigorous arguments, but rather of understanding the core ideas in the proofs. Though Grothendieck based his work on a general theory of topoi rather than give proofs only in the special case of etale topoi of schemes, it doesn’t follow that one must do things that way (as is readily seen by reading any other serious book on etale cohomology, where universes are irrelevant and proofs are completely rigorous).

In other words, what is needed to create a rigorous “theory of everything” need not have anything to do with what is needed for the more limited aim of developing a “theory of something”. Mochizuki does speak of “change of universe” in a serious way in his 4th and final IUT paper (this being a primary reason for the word “inter-universal” in “IUT”, I believe). But that consideration of universes is due to seeking a very general framework for certain tasks, and does not appear to be necessary if one aims for an approach that is sufficient just to prove Szpiro’s Conjecture. For the purposes of setting up a general framework for IUT strong enough to support all manner of possible future developments without “reinventing the wheel”, the “inter-universal” considerations may be necessary, and someone at the Oxford workshop suggested model theory could provide a well-developed framework for such matters, but for applications in number theory (and in particular the ABC Conjecture) it appears to be irrelevant.

4. What happened at the workshop?

The schedule of talks of the workshop aimed to give an overview of the entire theory. The aim of all participants with whom I spoke was to try to identify where substantial contact occurs between the theory of heights for elliptic curves (an essential feature of Szpiro’s Conjecture) and Mochizuki’s past work in anabelian geometry, especially how such contact could occur in a way which one could see did provide insight in the direction of a result such as Szpiro’s conjecture (rather than just yield non-trivial new results on heights disconnected from anything). So one could consider the workshop to be a success if it gave participants a clearer sense among:

- the “lay of the land” in terms of how some ingredients fit together,

- which parts of the prior work are truly relevant, and in what degree of generality, and

- how the new notions introduced allow one to do things that cannot be readily expressed in more concrete terms.

The workshop helped with (i) and (ii), and to a partial extent with (iii).

It was reasonable that participants with advanced expertise in arithmetic geometry should get something out of the meeting even without reading any IUT-related material in advance, as none of us were expecting to emerge as experts (just seeking basic enlightenment). Many speakers in the first 3 days, which focused on material prior to the IUT papers but which feed into the IUT papers, were not IUT experts. Hence, they could not be expected to identify how their topic would precisely fit into IUT. It took a certain degree of courage to be a speaker in such a situation.

The workshop began with a lecture by Shou-Wu Zhang on a result of Bogomolov with a group-theoretic proof (by Zhang, if I understood correctly) that is not logically relevant (Mochizuki was not aware of the proof until sometime after he wrote his IUT papers) but provided insight into various issues that came up later on. Then there was a review of Mochizuki’s papers on refined Belyi maps and on elliptic curves in general position that reduced the task of proving ABC for all number fields and Vojta’s conjecture for all hyperbolic curves over number fields to the Szpiro inequality for all elliptic curves with controlled local properties (e.g., semistable reduction over a number field that contains sqrt{-1}, j-invariant with controlled archimedean and 2-adic valuations, etc.). This includes a proof by contradiction that was identified as the source of non-effectivity in the constants to be produced by Mochizuki’s method (making his ABC result, if correct, well-suited to finiteness theorems but with no control on effectivity).

Next, there were lectures largely focused on anabelian geometry (for hyperbolic curves over p-adic fields and number fields, and various classes of “reconstruction” theorems of geometric objects and fields from arithmetic fundamental groups). Slides for many of the lectures are available at the webpage for the workshop.

The third day began with two lectures about Frobenioids. This concept was developed by Mochizuki around 2005 in a remarkable degree of generality, beyond anything eventually needed. A Frobenioid is a type of fibered category that (in a special case) retains information related to pi_1 and line bundles on all finite etale covers of a reasonable scheme, but its definition involves much less information than that of the scheme. Frobenioids also include a feature that can be regarded as a substitute for missing Frobenius maps in characteristic 0. The Wednesday lectures on Frobenioids highlighted the special cases that are eventually needed, with some examples.

At the end of the third day and beginning of the fourth day were two crucial lectures by Kedlaya on Mochizuki’s paper about the “etale theta function” (so still in a pre-IUT setting). Something important emerged in Kedlaya’s talks: a certain cohomological construction with p-adic theta functions (see the appendix). By using Mochizuki’s deep anabelian theorems, Kedlaya explained in overview terms how the cohomological construction led to the highly non-obvious fact that “everything” relevant to Szpiro’s Conjecture could be entirely encoded in terms of a suitable Frobenioid. That shifted the remaining effort to the crucial task of doing something substantial with this Frobenioid-theoretic result.

After Kedlaya’s lectures, the remaining ones devoted to the IUT papers were impossible to follow without already knowing the material: there was a heavy amount of rapid-fire new notation and language and terminology, and everyone not already somewhat experienced with IUT got totally lost. This outcome at the end is not relevant to the mathematical question of correctness of the IUT papers. However, it is a manifestation of the same expository issues that have discouraged so many from digging into the material. The slides from the conference website link above will give many mathematicians a feeling for what it was like to be in the audience.

5. Audience frustration.

There was substantial audience frustration in the final 2 days. Here is an example.

We kept being told many variations of “consider two objects that are isomorphic,” or even something as vacuous-sounding as “consider two copies of the category D, but label them differently.” Despite repeated requests with mounting degrees of exasperation, we were never told a compelling example of an interesting situation of such things with evident relevance to the goal.

We were often reminded that absolute Galois groups of p-adic fields admit automorphisms not arising from field theory, but we were never told in a clear manner why the existence of such exotic automorphisms is relevant to the task of proving Szpiro’s Conjecture; perhaps the reason is a simple one, but it was never clearly explained despite multiple requests. (Sometimes we were told it would become clearer later, but that never happened either.)

After a certain amount of this, we were told (much to general surprise) variations of “you have been given examples.” (Really? Interesting ones? Where?) It felt like taking a course in linear algebra in which one is repeatedly told “Consider a pair of isomorphic vector spaces” but is never given an interesting example (of which there are many) despite repeated requests and eventually one is told “you have been given examples.”

Persistent questions from the audience didn’t help to remove the cloud of fog that overcame many lectures in the final two days. The audience kept asking for examples (in some instructive sense, even if entirely about mathematical structures), but nothing satisfactory to much of the audience along such lines was provided.

For instance, we were shown (at high speed) the definition of a rather elaborate notion called a “Hodge theater,” but were never told in clear succinct terms why such an elaborate structure is entirely needed. (Perhaps this was said at some point, but nobody I spoke with during the breaks caught it.) Much as it turns out that the very general theory of Frobenioids is ultimately unnecessary for the purpose of proving Szpiro’s Conjecture, it was natural to wonder if the same might be true of the huge amount of data involved in the general definition of Hodge theaters; being told in clearer terms what the point is and what goes wrong if one drops part of the structure would have clarified many matters immensely.

The fact that the audience was interrupting with so many basic questions caused the lectures to fall behind schedule, which caused some talks to go even faster to try to catch up with the intended schedule, leading to a feedback loop of even more audience confusion, but it was the initial “too much information” problem that caused the many basic questions to arise in the first place. Lectures should be aimed at the audience that is present.

6. Concluding thoughts

Despite the difficulties and general audience frustration that emerged towards the end of the week, overall the workshop was valuable for several reasons. It improved awareness of some of the key ingredients and notions. Moreover, in addition to providing an illuminating discussion of ideas around the vast pre-IUT background, it also gave a clearer sense of a more efficient route into IUT (i.e., how to navigate around a lot of unnecessary material in prior papers). The workshop also clarified the effectivity issues and highlighted a crucial cohomological construction and some relevant notions concerning Frobenioids.

Another memorable feature of the meeting was seeing the expertise of Y. Hoshi on full display. He could always immediately correct any errors by speakers and made sincere attempts to give answers to many audience questions (which were often passed over to him when a speaker did not know the answer or did not explain it to the satisfaction of the audience).

If the final 2 days had scaled back the aim to reach the end of IUT and focused entirely on addressing how the Frobenioid incarnation of the cohomological construction from Kedlaya’s lectures makes it possible (or at least plausible) to deduce something non-trivial in the direction of Szpiro’s Conjecture (but not necessarily the entire conjecture) then it would have been more instructive for the audience. Although “non-trivial” is admittedly a matter of taste, I do know from talking with most of the senior participants that most of us did not see where such a deduction took place; probably it was present somewhere in a later lecture, but we were so lost by everything else that had happened that we missed it.

I don’t understand what caused the communication barrier that made it so difficult to answer questions in the final 2 days in a more illuminating manner. Certainly many of us had not read much in the IUT papers before the meeting, but this does not explain the communication difficulties. Every time I would finally understand (as happened several times during the week) the intent of certain analogies or vague phrases that had previously mystified me (e.g., “dismantling scheme theory”), I still couldn’t see why those analogies and vague phrases were considered to be illuminating as written without being supplemented by more elaboration on the relevance to the context of the mathematical work.

At multiple times during the workshop we were shown lists of how many hours were invested by those who have already learned the theory and for how long person A has lectured on it to persons B and C. Such information shows admirable devotion and effort by those involved, but it is irrelevant to the evaluation and learning of mathematics. All of the arithmetic geometry experts in the audience have devoted countless hours to the study of difficult mathematical subjects, and I do not believe that any of us were ever guided or inspired by knowledge of hour-counts such as that. Nobody is convinced of the correctness of a proof by knowing how many hours have been devoted to explaining it to others; they are convinced by the force of ideas, not by the passage of time.

The primary burden now is on those who understand IUT to do a better job of explaining the main substantial points to the wider community of arithmetic geometers. Those who understand the work need to be more successful at communicating to arithmetic geometers what makes it tick and what are some of its crucial insights visibly relevant towards Szpiro’s Conjecture.

It is the efficient communication of great ideas in written and oral form that inspires people to invest the time to learn a difficult mathematical theory. To give a recent example, after running a year-long seminar on perfectoid spaces I came to appreciate that the complete details underlying the foundational work in that area are staggeringly large, yet the production of efficient survey articles and lectures getting right to the point in a moderate amount of space and time occurred very soon after that work was announced. Everything I understood during the week in Oxford supports the widespread belief that there is no reason the same cannot be done for IUT, exactly as for other prior great breakthroughs in mathematics. There have now been 3 workshops on this material. Three years have passed. Waiting another half-year for yet another workshop is not the answer to the current predicament.