We’re having the wrong conversation about Apple and the FBI

We’re having the wrong conversation about privacy in the U.S.. The narrative is focused on how the bullies at the FBI are forcing the powers for good over at Apple to hand over data that they’d rather protect for the good of all.

Here’s the conversation I’d rather be having: why our government is not protecting our privacy. Instead, we are reduced to relying on an enormous, profit seeking corporation to make a stand for our rights. At the end of the day this argument dumbs down to “Apple good, government bad” and it’s far too easy and concedes far too much. We need to think harder and demand more.

Keep in mind a few things. Apple is not accountable to us. They are a private company. When people want to argue otherwise, they say that we “vote with our dollars” for Apple. But that just means that consumers affect gadget design, which includes safety and security features. At the end of the day, though, Apple is accountable to the laws of the land, and they will and have turned over all kind of private data about users when the law forces them to. They are not heroes, because they cannot be, even if they wanted to be.

I want to stop talking about Apple, and its operating systems, and so on. That’s all a sideshow. I want to talk about demanding a government that will acknowledge that its duty is to protect privacy while investigating risks. Right now the FBI is falling far short, trivializing the risk to the rest of us when backdoors are created and used at scale. They have made an internal calculation that the trade-offs are well worth the risks, without really having a conversation with the public in which they even measure the risks. And those risks are our risks.

And yes, that is complicated, nuanced, and there are plenty of conflicts of interest involved, which are hard to balance. But that’s the thing about governing in a democracy: we need to have the conversation, and the government needs to stay accountable to all of us. Let’s stop talking about Apple and start talking about democracy in the era of big data.

The unreasonable delightfulness of Mathematics, Substance and Surmise

I’ve been (slowly) reading my friend Ernie’s newest book called Mathematics, Substance and Surmise. It’s been published by Springer and is available now for purchase or what looks like a free download (update! I get it free because I’m on Columbia internet).

Actually he wrote it with his dad, which is freaking adorable, and also it’s actually not strictly written by them: it’s a collection of delightful essays on the ontology of mathematics from all sorts of perspectives.

Full disclosure: Ernie is a friend of mine, who was a generous and patient reader for my forthcoming book, and as such I am of course disposed to love his book. He even mentions my book in the introduction to his, so obviously he’s written an amazing book. But here’s the thing: actually, he has written an amazing book.

Fuller disclosure: I haven’t read the whole book yet. I tried to wait until I was done before blogging about it, but I just couldn’t because I am bubbling over with excitement, and as we all know bloggers are notoriously bad at impulse control. But I also feel like I could blog separately about each essay, so there’s always the possibility I might blog again later on about the rest of the book.

It’s a long book, too, chock full of entirely different ideas and perspectives. Which means that what I have read of this book, I have taken in slowly, because it’s really dense and fascinating and I haven’t wanted to miss anything. Whether it’s thinking about how mathematics and mathematical collaboration is done now versus in the olden days, or how computers have become full partners with mathematicians (what does it mean to “know” a formula for the 4th power of pi is true without having a proof for it?) or how robots should think about space – an unreasonably entertaining and delightful essay written by Ernie himself, which involves pictures of cheese graters and string bags – or indeed thinking about whether mathematical objects exist (is the number 2 a noun or an adjective? Is mathematics about the world or only about itself?), the book consistently makes you think differently, while also giving you substantive and grounded mathematical context in which to do your thinking.

One thing that excited me while reading it yesterday was the possibility that I’ve finally found the space in which to discuss my long-held theory that the sun actually goes around the earth. Not that I think this is a precise and accurate statement, but rather that it’s imprecise yet true, and that when someone corrects me and tells me the earth goes around the sun, that becomes another statement which is of course more precise and accurate statement but still not entirely precise and accurate! So why am I wrong and they’re right? What do humans mean when they say something’s right, anyway?

So I guess what I’m asking is, can I get together with all the people who wrote all the essays in this book and have a long series of dinner parties with them? And I know that’s a common evanescent urge that people have when they read books and really like them, but in my case I actually mean it.

Please, authors of the essays in Mathematics, Substance and Surmise, come by my house any time (give me like 3 hours warning) and discuss stuff with me about the way we think about and do mathematics. I’ll cook.

Neoliberalism is being challenged

Don’t know about you, but I think neoliberalism, which has been a prevailing ideology for the past 40 years, is being challenged this year like never before.

Let me start my argument with a discussion of the newest AltBanking essay, entitled Freedom in the Neoliberal Eden. In the essay, we make the case that the citizens of Flint, Michigan and Ferguson, Missouri are living lives of extreme freedom and liberty, at least if you define those concepts as a neoliberalist would. They are extreme cases, to be sure, but also 100% natural consequences of their political and economic environment. From the essay:

When nothing trickles down, when boats don’t rise, here is the explanation that follows: it is not the system that it is at fault, but the character of those people who failed to prosper in it. In this supposedly radically free landscape, you will find yourself entwined in an unsatisfiable obligation. Yes, there is the ever-present Prosperity Gospel stuff we hear from the Christian right, but there is also an even wider-scale acceptance of financial responsibility, credit worthiness, and general economic success – whether earned or not – as equivalent to moral uprightness.

Feel free to read the entire essay, which is powerful.

It’s also not entirely pessimistic. It ends with the hopeful thought that the Ferguson Report was, after all, generated by our Justice Department. Perhaps it can or will be seen as an inflection point in the history of neoliberal politics in the U.S..

In fact, there are more hopeful signs if you look for them.

For example, yet another attempt at social impact bonds, which is a way to hand huge social problems over to “the private sector” to solve, has failed. I’ve written about this before as a bad idea, so I won’t go into all my reasons that Goldman Sachs won’t solve mass incarceration (key word: gaming).

More generally though, we shouldn’t expect a neoliberalized private sector economy to address problems that stem from inequality. If you find yourself trying to financialize things like incarcerated teens and early childhood education for poor kids, you’re likely not going to see the point of long-term investments like GED preparation classes for prisoners, which cost money now but have few easily measurable benefits.

Simply stated, there are some things that government should actually provide to everyone, like education and economic opportunity, where private companies will always want to pick and choose who will be more profitable. I think this is sinking in, slowly.

Here’s another spark of hope: politics. I know, it’s hard to find much inspiration in that chaos, but one obvious point to make is that voters are not entirely buying into the standard SuperPAC-funded corporatist politics. Granted, it’s taking an ugly turn on the GOP side, but it’s interesting nonetheless. And since I’m looking for good news, I’ll consider this as such.

Finally, the recent Congressional action that removed No Child Left Behind is a concession from policy makers that educational institutions do not benefit from being run like businesses, and naive metrics of success when it comes to truly difficult problems only serve to distract and trivialize.

In his new book The Only Game In Town, Mohamed El-Erian describes two possible near futures for the world economy: in the first, we go to hell in a hand basket characterized by economic stagnation, radicalized politics and social unrest, destructive inequality, and resource wars between nations.

In the second possible future, the elected governments of the world acknowledge the major roles they play in a peaceful future. They pick themselves up off their collective asses, take their responsibilities seriously – and in particular take the economic reins from central bankers – and start providing the services, infrastructure, progressive tax systems, and opportunities that their constituents need.

I’m hoping the second thing happens.

President Archie Bunker

Last night I had a strange but vivid dream that Archie Bunker had just been elected president. He had brought along all of his racist, misogynistic, antisemitic, and homophobic thoughts and mannerisms. In this alternative dream world, the influence of his liberal son-in-law Mike was nowhere to be found.

Now, keep in mind that Archie Bunker, the main character of the TV show All in The Family, was popular when I was a newborn baby – I was born in 1972 – and that the opinions expressed by the title character were laughably old-fashioned at the time. And yet, I think my dream makes sense.

Why do I say that? When I woke up, I was intrigued and looked up Archie Bunker on wikipedia. Did you know:

- Show creator Norman Lear originally intended that Bunker be strongly disliked by audiences

- It didn’t work: Archie Bunker was hugely beloved by viewers and was even voted TV’s #1 character in 2005

- Rather than being motivated by malice, he is portrayed as hardworking, a loving father and husband, as well as a basically decent man whose views are merely a product of the era and working-class environment in which he has been raised

- There was something called the “Archie Bunker voting bloc” in the 1972 presidential elections

- as well as a parody “Archie Bunker for president” campaign

I guess my question is, how much of a parody is this really?

As a child, I didn’t get why people liked Archie Bunker. But I did love the opening song.

Book cover, bluegrass, and bagels

Book Cover

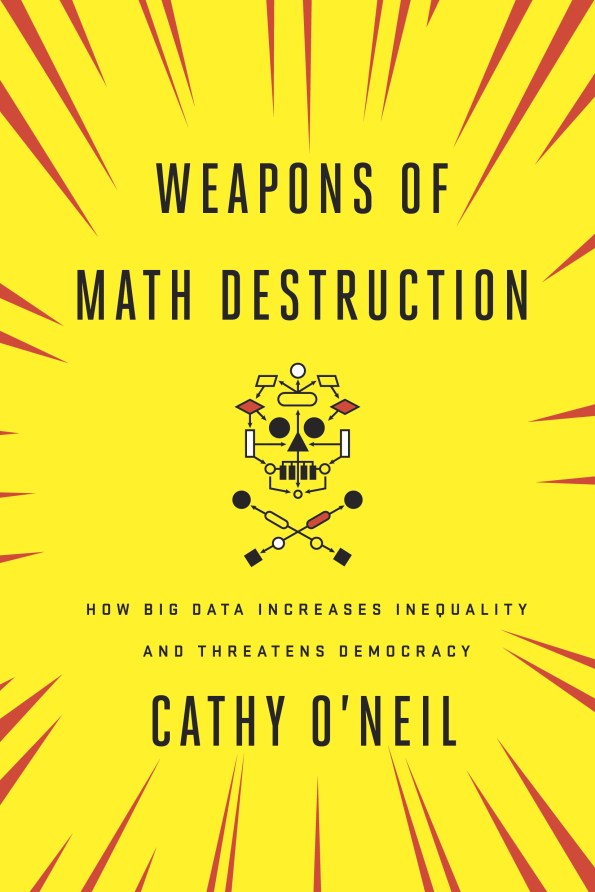

Holy crap, people, my book cover is finally public and it’s amazing and I want you all to agree with me about that:

Please go ahead and pre-order my book on Amazon (or directly from Crown Books).

And although I promised myself I wouldn’t, I’ve already started keeping track of its Amazon best selling rank. I’m proud to say that, more than six months before release date, it is the 714th best selling book in the category of statistical books inside of Educational & Reference books inside Business & Money books! Amazing, right? It’s also the 860,121th best selling book overall. Considering there are more than 129 million books overall, that’s pretty fucking amazing.

Maybe my book will be the 130 millionth book of all time.

Bluegrass and Bagels

Also! My band is playing a real live gig, taking place outside our homes or our friends’ homes, which I’m emphasizing because it’s a pretty big deal for us. I know you’ve all been waiting for this, so I’m super happy to tell you all about it and invite you to attend.

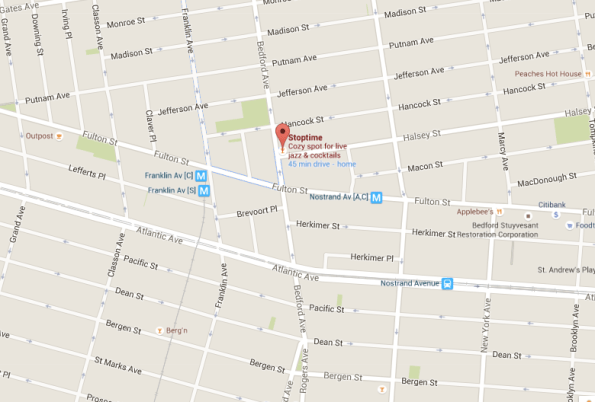

Here are the particulars:

- What: Bagels and Bluegrass. Free bagels and coffee should already be enough, right? But then you get to hear us play as well, doubling your pleasure. Also there’s a bar if you’d like to buy a mimosa. Think of it as a church alternative, but with booze.

- Date: this upcoming Sunday, February 21st

- Time: 11:30am-1:30pm or thereabouts

- Place: Stop Time in Brooklyn, close to the C train

- What to expect: bluegrassy folky music with a pinch of smokey jazz. Our set list includes covers of your favorites as well as quite a few originals by our extremely talented band members. Our harmonies are amazing and we err on the side of murder ballads.

- Finally, please follow us on Twitter or like us on Facebook if you’re into that kind of thing. And see you Sunday!

I’m a Morn Watcher

I’m watching Star Trek: Deep Space 9 for the second time through with my older sons. That’s the Star Trek series that you watch when you’ve recently watched all of Next Generation and Voyager and you’re feeling desperate.

It’s not that it’s a bad series – it’s pretty good, and sometimes great – but it doesn’t have the same sense of motion and progress as the others, partly because it’s set in a fixed place, namely a space station. Therefore, the story often revolves around recurring problems, namely the tension between Cardassians and Bajorans, which stems from a just-ended brutal Cardassian occupation.

Anyhoo, one other thing that happens on Deep Space 9 is that many of the characters are not Federation members, meaning that they don’t have military training at “The Academy.” Now, it makes sense for soldiers to be trained, but this Star Trek Academy is really a cross between Harvard and West Point, and the worshipping of the culture there can be really over the top (I’m looking at you, Wesley Crusher). So it’s nice to see Star Trek characters that have nothing to do with the military. They’re just hanging out.

Specifically, I’m talking about a character on Deep Space 9 called Morn.

Morn hangs out at a bar on the Deep Space 9 station owned and managed by Quark, who is a Ferengi (and thus famously obsessed with material wealth, in contrast with the rest of the socialist Federation) and a main character. And although by the second season or so Morn shows up very consistently, he never, ever speaks. Not once. Although, just to add to the mystery, other characters are sometimes heard complaining about how they were kept up all night listening to Morn’s stories.

My son Sander and I always keep an eye out for Morn – we noticed him about halfway through the first time we watched Deep Space 9 a few years ago – and we’ve recently gotten so obsessed with him that we scoured the web looking for Morn info and found out there was once something called the Morn Watchers, which is a fan club devoted to this speechless character.

They even had a quarterly magazine, probably containing all sorts of observations on how close Morn came to speaking recently. And how close he’s come to looking like Norm from Cheers who, legend has it, was the inspiration for Morn’s character.

Anyway, if there are any other Morn Watchers out there, I’m up for restarting the fan club. This can be taken as the initial newsletter.

Guest post: Math is the Great Equalizer

This is a guest post by Dr. Mark Tomforde. Mark is an associate professor at the University of Houston and passionate about making mathematics at all levels more accessible to members of underrepresented groups. He runs a math outreach program, called CHAMP, for high school and middle school students in inner-city Houston. Mark is also a mentor in the Math Alliance, which encourages undergraduate math students from all backgrounds to pursue graduate study, and he is the faculty advisor to his department’s undergraduate math club, Pi Mu Epsilon chapter, and AMS graduate chapter. In addition, he is an active researcher and the author of over 40 peer-reviewed articles and publications.

Dear Cathy,

I was very excited to see last week’s Atlantic article on BEAM and the excellent work of Daniel Zaharopol, as well as your follow-up post How do we make math enrichment less elitist? and the contribution by P.J. Karafiol about Math Circles of Chicago.

I’m writing to you let you know about our outreach program at the University of Houston. The mascot of the University of Houston is the Cougar, and our program is called the Cougars and Houston Area Math Program (CHAMP).

CHAMP primarily serves the Third Ward and Sunnyside. These communities are immediately adjacent to the university, and they suffer from poverty, unemployment, recreational drug use, and violent crime. In fact, the Third Ward / Sunnyside neighborhood is among the lowest income neighborhoods in America as well as one of the most dangerous areas in the U.S., with 1 out of 11 people the victim of a violent crime each year. (This is more dangerous than any neighborhood in New York, L.A., or Detroit, and only Baltimore has the dubious distinction of more dangerous neighborhoods.) There are thousands of children and young people in the The Third Ward / Sunnyside area as well as multiple public and charter high schools (some of which serve over a thousand students) and many middle and elementary schools.

For 11 weeks each semester, two days per week after school, CHAMP brings students from local neighborhoods to the university of Houston campus for math lessons and tutoring. The high school students participating in CHAMP are all minorities (black or hispanic) and approximately two-thirds are women. We currently work primarily with KIPP Sunnyside high school and serve approximately 20 to 30 high school students at each of our meetings.

One day per week CHAMP provides lessons for the high school students in a style similar to a Math Circle, with a different instructor each week introducing such topics as Mobius bands, logic puzzles, game theory, non-Euclidean geometry, or basic group theory. We use discovery based learning, give a variety of low-floor, high-ceiling problems, and help the students build communication skills by having them explain their findings at the board. University of Houston undergraduates and graduate students volunteer to serve as facilitators, and each works with a group of two or three high school students to answer questions and provide guidance during the lessons.

On the other day each week CHAMP provides tutoring, allowing the high school students to work on either math homework or SAT/ACT preparation. The tutors are all volunteers from the University of Houston, and we make a special effort to recruit from the UH Chapter of the National Society of Collegiate Scholars (NSCS), the UH Chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE), and teachHOUSTON (a UH program training undergraduates to be high school STEM teachers).

Each week we post materials from our lessons, as well as photos showing the students in action. You can see this semester’s lesson materials and photos here and also past semesters’ lesson materials and photos here. I think the photos, in particular, show how excited and positive the students are about their mathematical experiences in CHAMP. There is also a video of CHAMP describing some of our successes.

Bringing the students to the University of Houston campus has several benefits. First, the students get to see what a college campus is like. Second, since many of our facilitators and tutors are minorities or women, the students are exposed to role models and mentors, and they have the chance to see successful college students, many of whom are majoring in STEM subjects, that look like them and come from similar backgrounds. We also regularly hold discussions at the lessons in which the students can ask the facilitators questions about college life. In fact, one day we unexpectedly had only female high school students show up for a CHAMP lesson, due to some kind of after school sports try-outs that day of which we were unaware. We decided to use this opportunity, and scrapped our planned lesson to instead have an impromptu discussion on being a woman in math and science. The discussion was led by our female CHAMP facilitators, who are all successful women majoring in STEM fields at the University of Houston. The high school women asked questions touching on a number of important topics, and (without using the exact terms) they addressed issues related to lack of role models, stereotype threat, and the need to find allies when pursuing a STEM career. You can see photos from this CHAMP meeting here.

CHAMP has not only provided several benefits to the high school students, but also to the university students who volunteer. Moreover, these interactions have provided wonderful ways for the university to connect with the community. I have been asked by the high schools to use my university contacts to help find judges for local high school science fairs, to have university representatives host booths at high school college fairs, and –most recently– to give a seminar to high school teachers and parents on best practices in building math skills.

CHAMP has been running for three years, and we’ve grown throughout this time. We expanded from one day per week to our current two, we have increased the number of high school students we serve, and we have established pipelines for recruiting volunteers. At the same time, there have been many setbacks: difficulties getting the high school students to campus, the city of Houston closing the primary high school we partnered with so that we had to scramble to connect with another, and the difficulties of running the program with very little financial support.

We currently serve approximately 25 high school students, and this past year we were supported by a $5,500 MAA Tensor-SUMMA grant that we use to provide T-shirts, food, and transportation for the students. We also raise money through donations, which help us tremendously. We would like to expand CHAMP to more students. We just started a pilot program sending a few university students to a local middle school for math tutoring, and we would like to send a larger number of tutors next year. In addition, we want to bring more high school students to our twice-weekly meetings on campus. We have the space, as well as the facilitators and tutors to do this — our only obstacle is transportation to take the high school students to and from our campus. For this, we need more money.

Mathematics plays a special role in educational mobility. Many communities have state-mandated tests that must be passed for a student to graduate from high school. In underserved neighborhoods, it is often the math portion of these exams that present the largest obstacle to graduation. In addition, the standardized tests used for college admissions (PSAT, SAT, and ACT) largely focus on two sets of skills: English and Math. These tests are often primary factors in college/university admissions as well as in determining scholarships, access to honors programs, and other benefits a student will receive. On top of all this, studies have shown that math skills entering college are highly correlated with successful retention and graduation in STEM subjects (e.g., a freshman engineering student who has never had a chemistry or physics class but has good math skills will be much more successful than an entering college student who had high school courses in science and engineering but needs to take remedial math). Quality mathematics education can improve high school graduation rates, help students get into a better college with more support, and improve the chances of success for students majoring in STEM fields.

Universities are particularly well suited to help with the K-12 mathematics education in their communities — particularly those universities in areas near underserved schools systems (e.g., in large cities, areas of rural poverty, or near Native American reservations). Too often universities exist within a bubble, disconnected from their surrounding community. By looking beyond the bounds of the campus and engaging the surrounding K-12 schools, universities have a unique opportunity to improve the quality of their neighborhoods by educating those most in need. This involvement in the local community is not ancillary to a university’s educational mission, but rather central to it.

In the Atlantic article mentioned earlier, Daniel Zaharopol eloquently said “[Math ability] is spread pretty much equally through the population, and we see there are almost no low-income, high-performing math students. So we know that there are many, many students who have the potential for high achievement in math but who have not had opportunity to develop their math minds, simply because they were born to the wrong parents or in the wrong zip code.”

In my opinion, this is one of the greatest tragedies of the modern age. Imagine the loss of potential that is caused through this social inequity. What if the next Einstein or the next Steve Jobs or the person capable of curing cancer is born in poverty and attends an under-resourced school in inner city America? Their potential contributions will most likely be lost. It a frightening thought, and yet surely this must be happening all the time. The fact it happens in our own communities, within miles of where we live in work, should be additionally troublesome for those of us living in the first world.

On top of that, consider our primary objective in mathematics and STEM: To solve problems. Anyone who is regularly engaged in problem solving knows the usefulness of thinking outside the box and coming up with unconventional ideas. People from different background and with different experiences bring new perspectives and contribute novel approaches to problems. And yet, we have created a system in which only a homogenous group of individuals (often white men from certain types of socioeconomic backgrounds) ever have the chance to work on these problems. If we are actually interested in solving our problems, this just doesn’t make sense. We need to make access to education and careers in STEM fields available to everyone, so that we can benefit from the full strength and entire range of contributions that come from all members of our society.

Thanks again for your blog post describing the need for math programs to be more accessible to all students. It is a conversation more of us in the math world should be having.

If you know of anyone who would like to donate to CHAMP or volunteer to help with lessons or tutoring, please refer them to the CHAMP website: www.math.uh.edu/champ

Sincerely,

Dr. Mark Tomforde

Associate Professor of Mathematics at the University of Houston

Director of CHAMP

Guest post: A Math Circle that’s Breaking the Mold

This is a guest post by P.J. Karafiol. P.J. has been in high school education for 20 years, the last fifteen in Chicago Public Schools as a math teacher and department chair, curriculum coordinator, and, this year, Assistant Principal/Head of High School. P.J. is the head author for the ARML competition, the founder of Math Circles of Chicago, and until last year a dedicated math team coach. He lives with his wife, three children, and two dogs in Chicago, about a half-mile from the public high school he attended.

Dear Cathy,

I loved your post asking how we can make math enrichment less elitist, and I wanted to let you (and your readers) know about what we’re doing about that here in Chicago. In 2010, inspired in part by your post about why math contests kind of suck, my department (at Walter Payton College Prep) and I decided to start a math circle in Chicago. We rounded up some of our friends from the city and suburbs, used part of an award from the Intel Foundation as seed money, and launched the Payton Citywide Math Circle. We had three major tenets: that students should be solving challenging problems, not listening to lectures; that the courses should be open to anyone who wanted to join; and that the program should be 100% free.

We’ve grown tremendously in the five years since our first Saturday afternoon session. Renamed Math Circles of Chicago, we now run math enrichment programs after school and on Saturdays at five locations around the city, including some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. In 2011 we partnered with the University of Illinois at Chicago, and we’ve been excited to welcome professors from all five of Chicago’s major universities as teachers and partners. We currently serve 500 students in grades 5-12 (the vast majority in grades 5-8), and we provide them with opportunities they don’t get anywhere else: above all, the opportunity to do challenging mathematics in an environment of collaborative exploration. And, since 2013, we’ve sponsored Chicago’s only (and, to my knowledge, the nation’s second) youth math research symposium, QED. This year, over 150 students in grades 5-12 brought original math research projects to the symposium, and we’ve trained teachers across the city in how to support math research in their own classes.

You’re absolutely right that we need to make opportunities like this available to all students. When I was in fifth grade, I told my father I “hated math”. He responded by taking me to a local (university) bookstore to let me peruse the wall of yellow Springer books. After I opened and closed my third incomprehensible tome, he explained that mathematics was what was in those books; the subject I hated in school was arithmetic. But I was an only child; many of our students tell us that what they do at math circle–graph theory, number theory, geometry explorations, etc.–is nothing like what is taught in their math classes. Frankly, I wouldn’t call what we do math “enrichment” at all: for many of the kids we serve, math circle is the only exposure they get to what I (or my father) would call real mathematics.

Researchers such as Mary Kay Stein would agree with our assessment. Stein divides math tasks into four levels of complexity, from “memorization” (level 1) to following procedures (levels 2 and 3, depending on whether the procedures are connected to genuine mathematical content). She reserves the term “doing mathematics” for the highest level of her framework, when students are solving problems for which they haven’t yet learned a procedure. (You can find a summary of her framework here.) One area where we’re growing is that we’re trying to engage even more teachers from Chicago Public Schools–not just our founders–in teaching problem-based sessions, in the expectation that those experiences will change what they do in the classroom for their “regular” students, as those experiences did for us.

Although we’ve grown and evolved, we’ve never strayed from our initial tenets. The Intel money ran out long ago, but we’re entirely donor-supported; our families donate the majority of our annual operating costs on an entirely voluntary basis. (We call it the “NPR Model”: if you like what you hear and think it’s valuable, please contribute what you can.) Students still come from all over the city and still spend their time solving and discussing mathematics, generating questions as well as answering them–not listening to lectures or doing practice worksheets. And our only admission requirement is the same as it was in 2010: students have to write, by hand (no typing allowed!), a one-page essay about why they want to do math on Saturdays (or after school). We have a waiting list in the dozens for each of our three largest sites.

If your readers want to learn more, or to help out, I’d encourage them to visit our website at mathcirclesofchicago.org, or to email our executive director, Doug O’Roark, at doug (at) mathcirclesofchicago (dot) org. We can always use donations; the program costs us about $20 per student per Saturday, and many of our families can’t afford to give nearly that much. We also support other noncompetitive math opportunities for our students: in addition to telling them about programs like the University of Chicago’s Young Scholars Program (now as of 2015 our official partner), HCSSiM, MITES, and PROMYS, we subsidize travel and other expenses for students whose financial aid awards are insufficient.

We’re really excited about the work we’re doing in Chicago. We’ve shown that math circles can exist (and thrive) outside of traditional university environments, and that placing circles in schools and community centers–and partnering with local community organizations–brings more students, and a more diverse group of students. Our programs are currently growing faster than our fundraising–which is a great problem to have–so we really could use any support your readers want to give. We’d also welcome visitors; we’re excited to help people see real kids do real math.

After I left the bookstore that afternoon 34 years ago, I did come to love math–a love supported not just by math contests, but by wonderful opportunities to learn and do mathematics at Dr. Ross’s program at OSU and at HCSSiM, where you and I met in 1987. Without those programs, I would be a different person today. So thank you for drawing attention to this critical issue.

Sincerely,

P.J. Karafiol

Founder and President

Math Circles of Chicago

The Mount St. Mary’s story is just so terrible

I’m sure many of you have heard the story that a tenured professor, as well as a non-tenured professor, were fired recently by the president, Simon Newman, of Mount St. Mary’s school in Maryland.

The short version: Newman, a private equity asshole, got confused as to where he was working and decided to fire anyone who disagreed with him, referring to disloyalty as the cause.

The specific “act of disloyalty” one of the professors made was to allow a student newspaper to report a (true) comment the president didn’t want made public, namely:

“This is hard for you because you think of the students as cuddly bunnies, but you can’t,” Mr. Newman is quoted as saying. “You just have to drown the bunnies.” He added, “Put a Glock to their heads.”

OK, gross and shocking.

But personally, I was even more disgusted by the story behind this story, namely his underlying plan to get rid of students for the sake of improving the college’s “retention rate” and thus its ranking on the US News & World Reports College rankings, that scourge of higher education.

The original article from the student newspaper explains Newman’s unfuckingbelievable plan. From the article:

Mount St. Mary’s University, like all colleges and universities in the U.S., is required by the federal government to submit the number of students enrolled each semester. The Mount’s cutoff date for the Fall 2015 semester was Sept. 25, and the number of students enrolled as of that date would be the number used to compute the Mount’s student retention.

Newman was obsessed with getting rid of students and revealed this in an email:

Newman’s email continued: “My short term goal is to have 20-25 people leave by the 25th [of Sep.]. This one thing will boost our retention 4-5%. A larger committee or group needs to work on the details but I think you get the objective.”

How was he going to achieve this number?

The president’s plan to “cull the class” involved using a student survey that was developed in the president’s office and administered during freshman orientation.

The survey was going to be given to students and started out by describing itself as “based on some of the leading thinking in the area of personal motivation and key factors that determine motivation, success, and happiness. We will ask you some questions about yourself that we would like you to answer as honestly as possible. There are no wrong answers.”

The actual plan for the results of the survey were a bit different – they would be used to help compile a list of students to get rid of before the deadline. Just so gross, and a wonderful example of how an algorithm can be used for good or evil. Please read the rest of the article, it’s amazing journalism.

Holy crap, people, this gaming of the US News & World Reports model has got to stop, this shit is nuts. And it makes me wonder how many other places are doing stuff like this and not getting caught. I mean, at least at this university the president was stupid enough to tell the professors the plan, right?

How do we make math enrichment less elitist?

There’s a great article in the Atlantic that’s making waves on my Facebook page (granted, my Facebook feed has more than its share of math nerds).

Called The Math Revolution and written by Peg Tyre, the piece describes the recent proliferation of math education programs for young people, which include the old-fashioned things I grew up with like math team and HCSSiM, but also include new stuff I’ve heard about (Russian math circles, Art of Problem Solving) as well as stuff I’ve never heard of (MathPath, AwesomeMath, MathILy, Idea Math, sparc, Math Zoom, and Epsilon Camp).

What I like about this piece is it directly addresses something that has bothered me for years and has, frankly, kept me from devoting myself to creating or running one of these programs. Namely, the extreme elitism involved. From the article:

And since many of the programs are private, they are well out of reach for the poor. (A semester in a math circle can cost about $300, a year at a Russian School up to $3,000, and four weeks in a residential math program perhaps twice that.) National achievement data reflect this access gap in math instruction all too clearly. The ratio of rich math whizzes to poor ones is 3 to 1 in South Korea and 3.7 to 1 in Canada, to take two representative developed countries. In the U.S., it is 8 to 1. And while the proportion of American students scoring at advanced levels in math is rising, those gains are almost entirely limited to the children of the highly educated, and largely exclude the children of the poor. By the end of high school, the percentage of low-income advanced-math learners rounds to zero.

So my question today, dear readers, is how to address this problem, which I assume starts before kindergarten. Do we just expand math enrichment programs so much that they eventually become accessible to more people?

And beyond access, how could we possibly keep costs down, considering that the people who are competent to teach this stuff have other lucrative offers?

It’s clearly a transitioning problem to some extent, since once we have enough people who speak “fun math,” there will be enough people to train the next generation. And the beauty of math is that you really only need a stick in the sand (and time, and a devoted teacher and ready students) to make it happen.

Thoughts appreciated.

Time for One More

Hey if you haven’t read it yet take a look at this new blog, called Time for One More.

Gorgeous writing, and an inspiration for my new project on thinking about the elderly and technology.

Piece in Slate about ethical data science

Yesterday Slate published a piece I wrote for them entitled The Ethical Data Scientist. Take a look and tell me what you think, I enjoyed writing it.

One thing I call for in the essay is the teaching of ethics to aspiring data scientists, and yesterday some very cool professors from the Berkeley School of Information wrote to me and told me about their two classes on data science and ethics, one for undergrads and the other for graduate students. I seriously wish I could enroll in them!

Please tell me of other efforts in this direction if you know of them.

The one great thing about unfair algorithms

People who make their living writing and deploying algorithms like to boast that they are fair and objective simply because they are algorithmic and mathematical. That’s bullshit, of course.

For example, there’s this recent Washington Post story about an algorithm trained to detect “resting bitch face,” or RBF, which contains the following line (hat tip Simon Rose):

FaceReader, being a piece of software and therefore immune to gender bias, proved to be the great equalizer: It detected RBF in male and female faces in equal measure. Which means that the idea of RBF as a predominantly female phenomenon has little to do with facial physiology and more to do with social norms.

While I agree that social norms have created the questions RBF phenomenon, no algorithm is going to prove that without further inquiry. For that matter, I don’t even understand how the algorithm can claim to understand neutrality of faces at all; what is their ground truth if some people look non-neutral when they are, by definition, neutral? The answer entirely depends on how the modeler creates the model, and those choices could easily contain gender bias.

So, algorithms are not by their nature fair. But sometimes their specific brand of unfairness might still be an improvement, because it’s at least measurable. Let me explain.

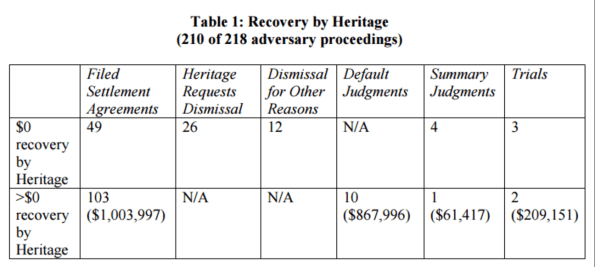

Take, for example, this recent Bloomberg piece on the wildly random nature of bankruptcy courts (hat tip Tom Adams). The story centers on Heritage, a Texas LLC, which bought up defaulted mortgages and sued 210 homeowners in court, winning about half. Basically that was their business plan, a bet that they’d be able to get lucky with some judges and the litigation courts because they knew how to work the system, even though in at least one case it was decided they didn’t even have standing. Here’s the breakdown:

Now imagine that this entire process was embedded in an algorithm. I’m not saying it would be automatically fair, but it would be much more auditable than what we currently have. It would be a black box that we could play with. We could push through a case and see what happens, and if we did that we might create a system that made more sense, or at least became more consistent. If we found that one case didn’t have standing, we might be able to dismiss all similar cases.

I’m not claiming we want everything to become an algorithm; we already have algorithmized too many things too quickly, and it’s brought us into a world where “big data blacklisting” is a thing (one big reason: the current generation of algorithms often work for people in power).

Algorithms represent decision processes that are vulnerable to inspection more than most human-led processes are. And although we are not taking advantage of this yet, we could and should do so soon. We need to start auditing our algorithms, at least the ones that are widespread and high impact.

Speaking at the Data Privacy Lab

I’m excited to be traveling to Harvard next Monday to give a talk at the Data Privacy Lab. The projects going on at the Data Privacy Lab are privacy-related: re-identification, discrimination in online ads, privacy-enhanced linking, fingerprint capture, genomic privacy, and complex-care patients.

My talk will not be entirely focused on privacy – it will basically be a somewhat technical version of my book followed by my proposals for technological tools that could address the problems associated with opaque, widespread, and destructive algorithms (my definition of a “Weapon of Math Destruction”. Specifically, I want to examine the question of how we understand a black-box algorithm in terms of measuring its outputs (as opposed to scrutinizing the source code).

The Data Privacy Lab is run by Latanya Sweeney, a hero of mine who did great work in detecting online discrimination in Google ads among other things. I’m hoping to meet her first because it’s always nice to meet your hero but also because, as the chief technologist at the Federal Trade Commission, she can give me perspective on the kind of technological tools that regulators such as the FTC and the CFPB might actually adopt (or develop).

In other words, I don’t want to spend 4 years developing tools that nobody would use. On the other hand, I have the impression that they generally speaking don’t know what kind of tools are possible.

Flint residents don’t need water bottles, they need democracy

I’ve been unimpressed with the recent coverage of the Flint water crisis. The overall message is that there’s been a “run of bad luck” but that certain generous people and corporations are coming to the rescue. If you believe the reports, we should be grateful for all the water bottles being flown in from Nestle and Walmart, and we should rest assured that water filters are being handed out and installed, even though they are inadequate.

In many of the articles on Flint, the switch from Detroit to the Flint River is mentioned, as is the concept of water as a human right, but not much more is explained. Specifically, there are two important questions left unanswered. First, how did this happen? And second, where else is it going to happen?

When you think about how Flint residents got into this situation, it’s critical to remember it was directly caused by a suspension in democracy. It was an emergency manager appointed by Michigan Governor Rick Snyder that made the switch to the Flint River as a water source. I’ve talked a bit about which municipalities get their democratic powers taken away; turns out that process often involves poor people of color. The entire point of emergency management is to remove accountability from the actors who put people’s lives in danger under the guise of saving money. Rick Snyder is, unbelievably, still in office.

Speaking of money, what’s the larger story here? It’s that, as a country, we can’t seem to pony up the resources to keep up our infrastructure, especially when it comes to water. A 2012 report by USA Today found that water prices had doubled in a quarter of the cities surveyed since 2000. This is because federal funding for water and waste systems have been reduced by 80% since 1977. And that would make sense if our water infrastructure were robust, but it’s not. In fact it’s in crisis, and we’d need $1 trillion to update it. The result is widespread crappy water, expensive water, and privatized water system disasters. We just let it rot at the local level, in other words, and deal with it – or not – in the most expensive ways, when it’s already an urgent situation.

Guess where the pipes are the oldest and most decrepit? You guessed it, where poor people live. When we ignore infrastructure we are inviting yet another punitive tax on the poor, and as it happens, a life-long debilitating level of lead poisoning.

So, let’s answer the second question: where else is this going to happen? The answer is pretty much everywhere unless we get our priorities straight. And I’m not talking about water bottles.

Raising kids the right way

Hey there’s finally been a New York Times column that agrees with me about how to raise kids, so I’m totally going to blog about it.

Seriously, I know that I’m 100% biased, as is anyone who tells you how to raise your kids, but I think Adam Grant has hit upon the perfect explanation of how I think about things in his recent column, How to Raise a Creative Child. Step One: Back Off.

The dumbed down version goes like this: yes, we all know it take a huge amount of practice to get good at the violin. But that doesn’t mean you should force your kids to practice all the time so they’ll become musicians. That’s confusing causation with correlation, the most common of all parental crimes. Instead, ask your kids to be ethical and trust them to find their passion.

The idea is if you give them a strong education in ethics, and then set them free within that framework, they might just decide they love the violin. If they do, then as long as you support their passion, they might just practice all the time and become musicians.

I’ve written a bunch about this exact issue over the years, because although I played the piano as a child, I don’t encourage my kids to play instruments. Because they aren’t begging for it like I did.

To be fair, this isn’t because I’m nervously trying to construct creative kids and want the conditions to be perfect. Mostly it’s common sense. Said plainly, why would I pay for expensive lessons that they don’t want? Why would I set myself up to remind them to practice when they could care less? It sounds like torture for everyone involved, and I honestly don’t understand parents who do it.

I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, a hotbed of striving upperly-mobile parenthood, and I was absolutely surrounded by kids – especially second-generation Asian kids – who were being forced to display precocity in all kinds of ways. These kids were miserable, and they hated their violins and cellos. Not all the time, and not in every way, but let me say it like this: very few of them still play music. (Whereas I do, and by the way my bluegrass band has a gig, stay tuned.)

I know, it’s not a lot of evidence, but I still think I’m right, because it’s parenting and people are totally irrational when it comes to this kind of thing, so bear with me, and read the references in Adam Grant’s piece as well, maybe they’re scientific-y.

Of course, it all depends on the definition of creative, which is of course not obvious and I could easily imagine the result changing depending on how you do it. Not to mention that “creativity” isn’t the only thing you’d want from your children. In fact, it’s not my personal goal for my kids to be creative. If I had to choose, I’d say I want my kids to be generous and ethical.

Here’s a bit more background on this very question. a Harvard Education School report called THE CHILDREN WE MEAN TO RAISE: The Real Messages Adults Are Sending About Values that found the following:

About 80% of the youth in our survey report that their parents are more concerned about achievement or happiness than caring for others. A similar percentage of youth perceive teachers as prioritizing students’ achievements over their caring. Youth were also 3 times more likely to agree than disagree with this statement: “My parents are prouder if I get good grades in my classes than if I’m a caring community member in class and school.” Our conversations with and observations of parents also suggest that the power and frequency of parents’ daily messages about achievement and happiness are drowning out their messages about concern for others.

When I read this report I performed an exceptionally biased poll in my own household and made sure my kids knew what’s up. And they all do, most probably because I am not forcing them to practice the piano.

At CPDP, thinking about privacy

Brussels is a pretty nice place for a hellhole (according to Trump). I got here early yesterday and walked around; obviously I bought a bunch (technically an asston) of chocolate and took pictures of impudent statues.

I know this sounds entirely unhistorical and arrogant, but I can’t help thinking that Brussels was created out of some indulgent American fantasy of Europe that confused Paris and Amsterdam and added a bunch of chocolate stores, beer, and waffles. Oh, and gold leaf.

It’s a great city; possibly it’s replaced Amsterdam as the place I’d like to live if I moved away from New York (which will never happen). It’s pedestrian dominated, there are plenty of sex shops, and the recycling bins are covered with graffiti. In other words, it’s got the right values and it’s not overly sanitized. Trump’s got it wrong once again.

I’m here for an annual conference called CPDP, which stands for Computers, Privacy, and Data Protection. This morning I attended a super interesting panel on privacy and the world’s poor. In that panel I learned about an algorithm being used to sort unemployed people in Poland. As is typical of many of the algorithms I’m interested, it’s both entirely opaque and high impact; the open information laws also don’t apply for inscrutable reasons.

Later today I’ll be on a panel in which we’ll discuss software tools that investigate privacy and data protection in the real world. Besides me, the people on the panel are working within the context of European privacy and protection laws, which are both very different and much more protective than we have in the states (although the UK is an exception). I will surely learn a lot, both about how people think about data and privacy over here and what the obstacles are to enforcing the strong laws.

The continued surveillance of poor black kids

There’s a new data-driven app out there called Kinvolved, featured this morning in the New York Times, and it’s exactly my worst fear. It tracks Harlem school children’s whereabouts, sending text messages to parents when they are tardy or absent from school.

When you look at the user agreement, it seems to say that the data is relatively safe and presumably not available for resale to marketers, but they also say they are allowed to change the agreement at any time.

Here’s my specific fear: what about when they go out of business? I’m thinking the data might be valuable at that point, and their investors might want some money back. And there’s a market, too: data brokers would love to get their grubby little hands on such data to add a layer to their profiles of poor black and brown kids.

This is a situation where FERPA, which is the federal child privacy law, is clearly not strong enough. Right now FERPA allows Kinvolved to be designated as “school officials” who have a “legitimate interest” in using and accessing any education records. And once they have that data, I don’t think there are real constraints to its use.

I’m not singling out Kinvolved for bad intentions; for all I know they mean well and they might even help some kids and families. But I don’t think the data the app is generating is being adequately protected, and it is yet again data concerning the nation’s most vulnerable population.

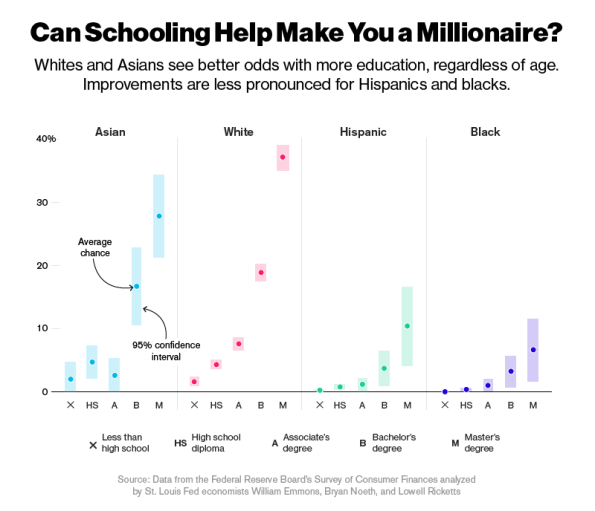

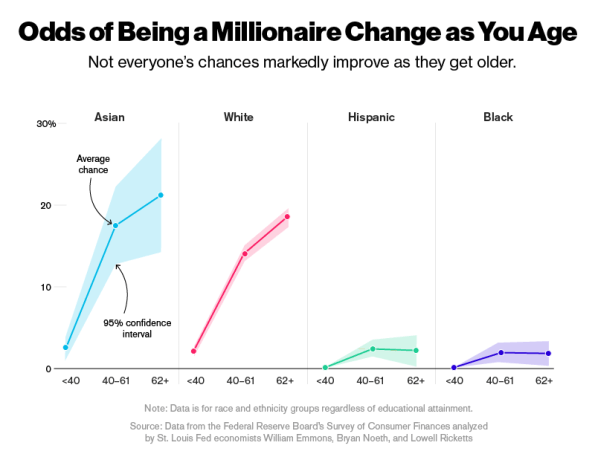

Race and the race to the top

Bloomberg has a pretty amazing article today with two fantastic graphs. Here’s the article, but the graphs pretty much say it all.

Todd Schneider’s “medium data”

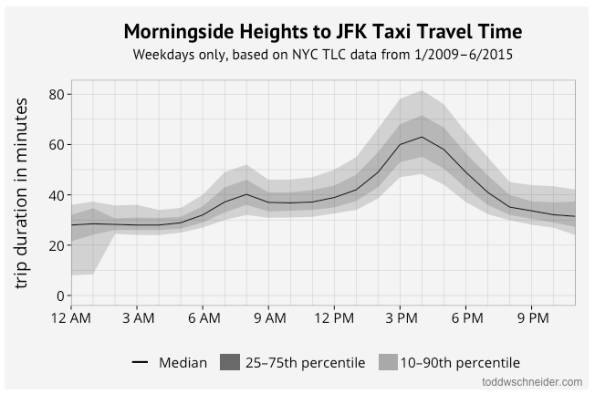

Last night I had the pleasure of going to a Meetup given by Todd Schneider, who wrote this informative and fun blogpost about analyzing taxi and Uber data.

You should read his post; among other things it will tell you how long it takes to get to the airport from any NYC neighborhood by the time of day (on weekdays). This corroborates my fear of the dreader post-3pm flight.

His Meetup was also cool, and in particular he posted a bunch of his code on github, and explained what he’d done as well.

For example, the raw data was more than half the size of his personal computer’s storage, so he used an external hard drive to hold the raw data and convert it to a SQL database on his personal computer for later use (he used PostgreSQL).

Also, in order to load various types of data into R, (which he uses instead of python but I forgive him because he’s so smart about it), he reduced the granularity of the geocoded events, and worked with them via the database as weights on square blocks of NYC (I think about 10 meters by 10 meters) before turning them into graphics. So if he wanted to map “taxicab pickups”, he first split the goegraphic area into little boxes, then counted how many pickups were in each box, then graphed that result instead. It reduced the number of rows of data by a factor larger than 10.

Todd calls this “medium data” because, after some amount of work, you can do it on a personal computer. I dig it.

Todd also gave a bunch of advice for people to follow if they want to do neat data analysis that gets lots of attention (his taxicab/ Uber post got a million hits from Reddit I believe). It was really useful and good advice, the most important of which was, if you’re not interested in this topic, nobody else will be either.

One interesting piece of analysis Todd showed us, which I can’t seem to find on his blog, was a picture of overall rides in taxis and Ubers, which seemed to indicate that Uber is taking over market share from taxis. That’s not so surprising, but it actually seemed to imply that the overall number of rides hasn’t changed much; it’s been a zero-sum game.

The reason this is interesting is that de Blasio’s contention has been that Uber is increasing traffic. But the above seems to imply that Uber doesn’t increase traffic (if “the number of rides” is a good proxy for traffic); rather, it’s taking business away from medallion cabs. Not a final analysis by any stretch but intriguing.

Finally, Todd more recently analyzed Citibike rides, take a look!