Archive

Stop and Frisk silent march today

It’s Father’s Day, and if you read the wikipedia article about the origins of Father’s Day you’ll find pretty much what you expect, namely it was started about 100 years ago (1910) and was only successful after the necktie and tobacco industries starting to promote it. In fact the only surprising thing I learned was that it was originally spelled “Fathers’ Day.”

Growing up, my mom always referred to these kinds of days as “Hallmark Holidays,” by which she meant that they were simply created by vendors wanting you to feel like you need to consume. For the record our family tradition is to give the celebrated person in question breakfast in bed but not to spend extra money.

It makes me wonder, though: what would Father’s Day be in the best of worlds, in some abstract place where it isn’t propelled by crude consumerism and sentimentality?

I got nothing. I’m too used to our shallow take on it.

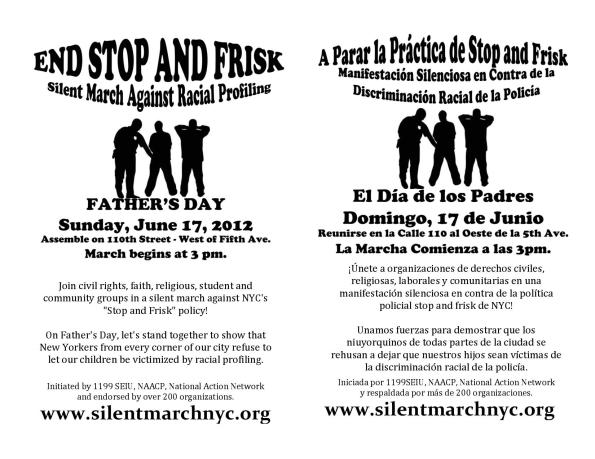

But I do have a feeling that a nice first approach would be to join the Silent March to stop Stop and Frisk, today at 3pm: Assemble on West 110th St. between Central Park West/8th Ave. and Fifth Ave.

On being an alpha female

About 8 months ago I found out I’m an alpha female. What happened was, one day at work my boss mentioned that he and everyone else is afraid of me. I looked around and realized he was pretty much right (there are exceptions).

I went home to my husband and mentioned how weird it was that people at work are afraid of me, and he said, “No, it’s not weird at all. Don’t you realize that you’re constantly giving people the impression that you’re about to take away their toy and break it??”. No, I hadn’t realized that – and that sounds pretty awful! Am I really that mean? Then he told me I was an alpha male living in a woman’s body.

If you google “alpha male in a woman’s body,” (without the quotes) which I did, you come upon the phrase “alpha female” pretty quickly.

It came as a surprise to me – I’d always thought I am nice. But it wasn’t a surprise to anyone else; in fact when I mentioned my realization to my close friends, each and every one of them laughed out loud that I hadn’t known this about myself. One of my friends told me it was less that I was about breaking toys and more about how I call out people’s bullshit, which is something I have to admit I relish doing.

Upon further reflection I had to admit to myself that I am nice, but only to people who I think are nice themselves. So I guess that means I’m not just simply nice. And if I enjoy calling people on their bullshit, that’s not exactly nice either.

Over the past 8 months, I’ve been slowly observing my alpha femaleness, and at this point I can honestly say I’m comfortable with it. I own it now. It’s kind of fun to know about it, because of how people react to me, without me intentionally doing anything.

How I now think about my alpha femaleness is that it lends me authority. It’s a kind of portable power. Not always, of course, and sometimes I am in situations where I’m totally incompetent, and sometimes I run into someone who completely ignores my alpha femaleness or is themselves an alpha male and competes. I usually really like them.

I’ve also realize how much my life has been informed by this property; my life has been, for the most part, much easier than it could have been without this property. And I want to acknowledge that because most people aren’t like this and don’t have this advantage.

For example: I interview really well. I speak with perceived confidence even when I don’t feel confident, and that comes across well in interviews.

In fact all my life people have mentioned to me that “things seem easy” to me, even in situations where I felt completely insecure and flustered. I used to lift weights at the gym with my buddies in college, and they would not really spot me on the bench press because they were convinced I didn’t need help. I almost dropped the weights on my neck a couple of times calling my friends over from the other side of the room. So in retrospect maybe it was a sign I’m an alpha female, but at the time I was just baffled.

It’s good and bad. When people perceive you as more confident and more comfortable in a situation than you actually are, it’s about 80% good and 20% bad, and could be the opposite depending on the situation. It’s bad when it’s dangerous and you really don’t know what you’re doing (that happened to me when I was driving an ATV once, and luckily when I turned it over in a mud pit I didn’t actually break my legs, but I could have) and it’s totally convenient when you’re presenting stuff or in an interview.

Why am I mentioning all of this? Because I think it might help people, especially women in math or in tech, to learn to think a bit more like an alpha female, and I want to give some tips on how to do it. It’s like injecting a shot of testosterone at the right time.

These tips can be used in specific situations like an interview or a talk or at a work meeting. Feel free to ignore these tips if you hate everything about the idea, which I would totally understand too. In fact when I first learned about it myself, I was offended by it on a matter of principle, but I’ve come to think of it more like a mysterious part of the human experience, on the same page as pheromones and how women have the same menstrual cycle when they live together.

Tips on how to think and act like an alpha female

- When you’re asked to describe your accomplishments, talk about yourself the way your best friend would describe you. So in other words with pride and enthusiasm for your accomplishments, without being embarrassed. Don’t lie or exaggerate, but don’t underplay anything.

- Let there be silence. If you’ve finished what you’re saying and you’re done, wait for someone else to say something.

- If you want credit, give credit first. Generosity is, in my experience, contagious. So if you want to get credit for contributing something to a project, start out by talking about how awesome your collaborators have been on the project. This gets people thinking about credit in a generous way, and it also gives you authority for bestowing it as the first person who brought it up. Note this is different from what I see lots of people do, namely not mentioning credit themselves and waiting passively for someone else to raise it (and to share it).

- Ignore titles and hierarchy. Those things are silly. You can talk to anyone at any time if you have a good idea.

- If you want feedback, give feedback. This includes to your boss (see previous tip). If you want to find out how you stand with someone, the best thing to do is to tell someone else how they stand with you. People love hearing about themselves. This works best when you can say something nice, but it also works when it’s a difficult conversation.

- Define your narrative. When your standing is in question, put out your version of the story first, for a couple of reasons – one is that you define the scope of the question, and the other is that your narrative is now the standard, and any one refuting it has to refute it.

- When you’re in a meeting and want to bring your point across in a room full of alpha males, think about defending or arguing for an idea, rather than for yourself. It helps with gaining confidence in your argument.

- Of course it also helps if your argument is water-tight, so practice making your points in your mind, and write them down beforehand if that helps.

- Develop a thick skin. When you say what you think first, there are plenty of people who might take offense and jump on you and be vicious. Sometimes it’s just a show of power. Keep an observer’s eye on that kind of reaction, and don’t take it personally, because it’s almost never about you really, it’s maybe about their relationship with their mom or something.

- At the same time, what’s cool about putting yourself out there is that people react and often point out how your thinking is flawed or lazy and you get to learn really, really quickly. Learning is the best part!

The engaged skeptic

Last night I read this article by Jane Brody in the New York Times, which was about staying optimistic and the various benefits of a can-do attitude, including health benefits.

At one point in her essay she defines optimism like this:

She wrote, “People can learn to be more optimistic by acting as if they were more optimistic,” which means “being more engaged with and persistent in the pursuit of goals.”

If you behave more optimistically, you will be likely to keep trying instead of giving up after an initial failure. “You might succeed more than you expected,” she wrote. Even if the additional effort is not successful, it can serve as a positive learning experience, suggesting a different way to approach a similar problem the next time.

But in another part of her essay it has been transformed:

Avoid negative self-talk. Instead of focusing on prospects of failure, dwell on the positive aspects of a situation.

In college, I would approach every exam, even those I had barely studied for, with the thought that I was going to do well. Time after time, this turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

So which is it? Does being optimistic mean I’ll be more engaged with an persistent in the pursuit of goals, or does it mean I’ll barely study for an exam and then talk myself into thinking I’ll do well? Because those two ways sound pretty different, if not downright opposite. And who wants to be around a lazy optimist?

I don’t want to quibble, but I think there’s a common and important conflation of the two ideas of engagement and naivety, and I’d like to separate them.

It’s possible, and very possibly more interesting, to have a can-do attitude but not be optimistic, or in other words to be an engaged skeptic.

Just because I work hard and devote myself to something doesn’t mean I’ve fooled myself into thinking it will be a piece of cake. But it does mean I don’t think it’s impossible, and it will only work if I try to make it work. It’s not likely to work but it’s worth trying. Many very hard and very worthwhile things are like that.

Finally, when Brody says “Focus on situations that you can control, and forget those you can’t”, I’d argue that’s often code for letting yourself off too easy.

I claim that, as an engaged skeptic, you shouldn’t really forget anything, because you should figure out how you can maybe affect it after all, or in some small way, or the system it lives in, even if it’s in the future, and even if the chances are it won’t work.

Buying organic doesn’t make you better than me

There was a recent study published here which described how people who viewed organic foods with annoyingly self-righteous names actually behave more selfishly than people who viewed “comfort food” or other, bland categories of food. The abstract:

Recent research has revealed that specific tastes can influence moral processing, with sweet tastes inducing prosocial behavior and disgusting tastes harshening moral judgments. Do similar effects apply to different food types (comfort foods, organic foods, etc.)? Although organic foods are often marketed with moral terms (e.g., Honest Tea, Purity Life, and Smart Balance), no research to date has investigated the extent to which exposure to organic foods influences moral judgments or behavior. After viewing a few organic foods, comfort foods, or control foods, participants who were exposed to organic foods volunteered significantly less time to help a needy stranger, and they judged moral transgressions significantly harsher than those who viewed nonorganic foods. These results suggest that exposure to organic foods may lead people to affirm their moral identities, which attenuates their desire to be altruistic.

I read the original study (and also a hilarious post riffing on it from jezebel.com), and found it interesting that the experimenters at least claimed to be unsure of the outcome of the study in advance (although they did cite another study in which people were more likely to cheat and steal after purchasing “green” products).

Specifically, they thought one of two things could happen: that the sense of elevation cause by staring at the organic labels could make them feel like part of a larger community and therefore more willing to volunteer, or else the “moral piggybacking” on a perceived good deed (i.e. organic food is good for the environment) would make them feel like they’d already done enough, and be less likely to be nice. It turns out the latter.

[As an aside, another study cited was one in which people assumed there were fewer calories in chocolate which was described as “fair trade”, which explains something to me about why those kinds of labels are so popular and also so ripe for fraud.]

The results of this study resonates with me: ever since Whole Foods opened I’ve had the impression that the people shopping there thought they’d done enough for the world simply by paying too much for produce and not being able to buy Cheerios (a pet peeve of mine). Haven’t you noticed how rude Whole Foods shoppers are? I’d rather be in a Stop and Shop check-out line any day.

In other words, I’m going through a major case of confirmation bias here. I’ve been a huge skeptic about the organic food movement since it began when I was in college at Berkeley. I’ve challenged a whole bunch of my friends on this (yes I’m an asshole) and I’ve noticed there are essentially two camps. One camp defends organic as good for the environment, the other camp defends organic as more nutritious.

For the environmentalists, my argument is that local produce is better than California organic produce, given that it’s been shipped across the country. It seems silly to me to be able to purchase organic blueberries imported from somewhere instead of locally grown blueberries. In fact I’m not sure where there’s good evidence that organic, locally grown produce is better for the environment than just locally grown produce.

The other camp defends organic as more nutritious, but that really drives me completely nuts, because if you flip that around the message is that we can let the poor people eat the toxic vegetables while we rich people eat the healthy stuff. It’s crazy! If there really is toxicity in our standard produce, then this is a huge problem for the country and we need to address it directly, rather than making a certain class of very expensive food.

WTF with girdles?!?

The post today has absolutely nothing to do with math, finance, data science, or Occupy Wall Street. I’ll get back to that stuff after venting.

Can I just say, as a bounteous 3-time mother, that I absolutely positively don’t understand the new-found popularity of girdles?

I was going to not mention it because it seems like the girdle-pushing crowd may get more attention than they deserve simply by being thought about, but it seems like it’s hit a certain crest of popularity that forces my hand.

So here’s what happened. For whatever reason I received a SPANX catalog in the mail, and just out of sheer disbelief that there could be a whole catalog of such nonsense, I took a look inside.

And do you know what I found out? I found out that many of the things in the catalog don’t even come in my size! That’s because they go down to like size 4. No, I’m not kidding. Plus, they also have girdles for men, no shit.

Then I came across this NYT article about corsets. From the article:

At Aishti, his store in Jackson Heights, Queens, Moussa Balaghi has begun carrying girdles in size “extra small,” because, to his shock, so many teenagers and even younger girls were coming in to request them. “Only chubby fat girls used to use this; now, everybody is,” he said, shaking his head. “If she has the smallest little thing at her waist, she wants to use this.”

WTF?!

May I ask, what is a young skinny woman doing thinking about crap like this? What is the point of them? I am honestly confused. Is the point to have something strapped around you, keeping you from breathing correctly, keeping you from biking around town or bending over, and generally confirming that you’re imperfect?

I actually object to all girdles, because I like to see people love and accept their bodies, which seems kind of hard when you’re wearing an ace bandage all over your body.

Something is going on here and it smells bad.

Google’s promotion policy sucks for women

I’m going to start this post with an excerpt from a comment of reader JoanDelilah from a couple of weeks ago, commenting on my post The meritocracy myth:

And at the end of the day, this also assumes that it is right and proper for a structure to be in place which requires you to *grab* tough/interesting work to prove yourself, as opposed to it being given to you. There is competition inherent in the foundational world-view behind that statement. Why so much competition? We are supposed to be on the same team and competing with other businesses, right? What about the woman who is happy to crush any assignment she is given but simply doesn’t want to have to compete for the assignments that will “prove” her abilities? Why must she step so far out of her comfort zone just in order for the company that pays her to make use of the talents they are paying her to use?

This really nails down what I see all the time with respect to women getting promoted or even just getting recognized for their achievements.

To paraphrase it, women tend not to compete for recognition as much as men, for whatever reason. Maybe they’ve been socialized not to, maybe it is a simple question of testosterone. I will go into why I think this happens below. But for now let me just say I get super pissed when a system has been set up to diminish the success of people simply because of this personality issue.

Google is one such system. At Google, one must self-promote. I believe the rule is that, after two quarters or so of getting good reviews, you are eligible to self-promote, but you don’t have to.

And guess what? That policy sucks for women. Women don’t do it as often. I’ll bet this is statistically significant, even though I don’t have the numbers. Hey Google, do the math on this policy! And then change it!

Here’s the first part of my theory of why this happens. Women are not as secure in their accomplishments. By the way, note I am not saying women are insecure and men are secure. I think it’s more like men are over-secure and women are realistic, kind of like those studies that shows that depressed people are realists and non-depressed people are optimists. I definitely have seen men who actually think they (individually) accomplished something which clearly took a team effort. Women are less likely to “forget” the help they received in making something happen. See this amazing blog rant on the subject from a professor at NYU.

Here’s the second part. Women tend to choose mentors (i.e. bosses or advisors) that are brilliant, thoughtful, and approachable. Typically this also means that those mentors are not the kind of bullying personalities that are best suited to promote their team. Even when one doesn’t have a choice in who your boss is, I claim this approach to pairing still happens in a business when that business decides who should be the boss of a woman.

Example in pure math: Yau at Harvard is famously dynasty-building with his students, but he’s probably not someone who has a tissue box in his office (to be fair I haven’t checked). I didn’t even consider taking Yau as my advisor, in part because he was super intimidating and seemed to challenge grad students with a ring of fire.

The reward for being brave in a situation like that are that he is fiercely loyal to his students once he accepts them, and helps them get great jobs. My point is that fewer women choose Yau-like personalities as their advisor (although it has to be said that Yau has had women students, including Columbia’s Melissa Liu). And thus fewer women end up with advisors that will land them jobs and give them good advice on how to get ahead. I just don’t think women are thinking about that aspect of a mentor the way men do (it’s also possible than men don’t think about it either but are less likely to shy away from rings of fire in general due to their “optimistic” egos).

I am not saying this is an easy problem to fix, because it’s not, and the best self-promoters will always do well no matter where they work. But I do think Google can do better than this; maybe they could think of something a bit more double-blind like the orchestra auditions.

Stop with the man-diets already, coffee is good for you.

Every now and then my husband goes on a “man-diet”, which is a term I’ve coined meaning a restriction that has absolutely no reasonable goal except the very last event, namely breaking the diet and thus having an awesome moment of relapse.

His favorite man-diet is the coffee man-diet. He’ll suddenly decide that his two espressos in the morning and two more during the day is too much and he “needs to cut down”. He’ll make it one coffee in the morning and one in the afternoon, and he’ll stare wistfully at my second (or third) morning espresso, complain vaguely of headaches, and generally be a space cadet (by which I mean more than usual).

This will go on for about 5 days or so, until one morning where he’ll wake up in an addict’s rage and rebelliously suck down two coffees whilst raving about the magical properties of caffeine.

This happens about once a year. Every time it happens I remind him that coffee is actually good for you and there’s no reason to try to break an addiction that’s doing you good- we don’t try to go off oxygen, do we?

Well here’s more evidence of that. And in case you’re wondering, yes I do ignore all negative evidence of any one of my theories, but in this case I’m pretty sure the evidence I collect on my side is quite a bit stronger than the stuff I ignore. From the Bloomberg article:

The study found that men who drank 2 to 3 cups a day had a 14 percent lower risk of dying from heart disease, 17 percent lower risk of dying from respiratory disease, 16 percent decreased chance of dying from stroke and a 25 percent lower risk of dying from diabetes than those who drank no coffee.

…

Women who consumed 2 to 3 cups of coffee a day had a 15 percent lower chance of dying from heart disease, 21 percent lower risk of dying from respiratory disease, 7 percent decreased chance of dying from stroke and a 23 percent lower risk of dying from diabetes.

Tech firm mindset to avoid like the plague

There was recently an article entitled “Silicon Valley Avoids ‘B Players’ Like the Plague” which got my attention. Go ahead and read it, it’s pretty short. Here’s the heart of the story:

And not only are companies able to achieve more with less people, they’re also wary of hiring anyone but the best engineers. This is sometimes called the “bozo factor.” The late Steve Jobs often talked about the importance of hiring nothing but “A players.”

The former Apple chief executive said to an interviewer in 1998: “You’re well advised to go after the cream of the cream. That’s what we’ve done. You can then build a team that pursues the A+ players. A small team of A+ players can run circles around a giant team of B and C players.”

To avoid hiring less than A players, companies can go to extremes. At Violin Memory, managers can spend up to half of their time on screening and interviewing candidates. Reference checking alone can eat up large portions of the day. Candidates typically provide three references, but hiring managers will then tap their own networks to make contact with up to five people who have worked with the person. “Your reputation follows you,” said Vice President of Marketing Matt Barletta.

First, you know it’s going to be dripping with compassion and thoughtfulness if it’s a Steve Job’s quote. Second, I’m sure those managers who spend half their day stalking candidates think they’re super productive, when all it says to me is that the more time you spend spinning your creative genius in an environment like this the better – not a good incentive in an industry that probably needs less spin and more skepticism.

Okay, so they have some nutty ideas about hiring people. You might want to consider how they go about firing people as well. From the article:

Jay Fulcher, chief executive of online video technology start-up Ooyala, says he’s “never fired someone fast enough. By the time you know that it’s time for them to go, it’s already too late.”

Ummm… okay, but maybe the work is amazing? From the article:

“It sucks people in, and it takes away from your family life,” says Vice President of Engineering Kevin Rowett. “We have to figure out, can people tolerate that level of intensity?”

Ummm… sure, okay. But maybe this is some kind of super creative environment where you’re expected to be quirky and spontaneous, and you’re not expected to follow rules? From the article (emphasis mine):

Landing a position at Kaggle, a San Francisco-based start-up that crowdsources data analysis problems, is considered such a score that the company is able to have potential candidates move to San Francisco for one to two weeks and audition for a job.

People, people. What the fuck? Are we still wondering why there aren’t enough women engineers in Silicon Valley?

Caveats: 1) the comments on that article are scathing and worth reading, and 2) this toxic mindset is also apparent in New York.

To my Libertarian friends

First, I’d like to say thank you to the people who have been writing me very nice comments about the PBS Frontline special. It’s cool that people dug it, and it makes me really glad I did it. Thanks!

Second, I had a blast with Reno the other night doing her “Money Talks” show. You should definitely check her out soon.

Also, I’m on my way to the third day of a modeling conference at the IMA (which is part of the University of Minnesota) called User-Centered Modeling. I’ll be speaking tomorrow and I expect to be blogging quite a bit on the other talks between now and Friday.

And with that, I’d like to use the rest of my GoGo Inflight Internet service to start a conversation about the libertarian mindset.

By the way, in spite of my annoyingly opinionated personality, I actually love having friends I disagree with. It feels much more comfortable to be around people who give me friction and challenge my opinions than to be around people who all think similarly to me.

Why? Because it’s a lot easier to spot other people’s hypocrisies than it is to spot one’s own hypocrisies. So if I’m around people who agree with me, we are all very likely being totally blind to something obviously flawed in our mindset, but nobody’s there to point it out.

With that in mind, I really do want this to be a conversation about why libertarians think the way they do- so please comment if you have something to say (and feel free to tell me not to post your comment). I’ll start with what I see as an hypocrisy of the libertarian perspective.

Namely, the cry I hear over and over from the libertarian in the room (whichever one happens to be there) is that big government and welfare and socialized programs are helping people out who should be able to make shit work on their own, whereas they never asked anyone for any help.

This myth of the “pulled myself up by the bootstrap” kind of drives me nuts. It’s like they completely ignore the system in which they lived and (usually) thrived, and how advantaged they are in that system.

When people go into that riff where they talk about how they never owe anybody any money, and they put themselves through college and don’t see why they should feel bad for the students nowadays who owe a collective $1,000,000,000,000 in student loans because they managed to be successful without extra help, here’s what I ask them: do you think you could have been as successful as you are if you’d been born a female subsistence farmer in Africa?

That’s kind of an easy one (and I go from there) but what it does it contextualize the idea of what it means to not ask for help. Namely, when you have a good infrastructure set up with a good education, available health care, etc, then you don’t need to ask for help, because you can help yourself. But it doesn’t mean you’re doing it all by yourself!

So, if you were born into an honest family with a good work ethic and strong skills and intelligence, then yes it’s possible to work really hard and do well, and I’m always proud of people who work really hard and do well, but it needs to be understood that anyone who is a success in our culture is a success partly because our culture allows for such success – and then there’s the individual contribution component which is much much much smaller.

Did you ever notice in the Ayn Rand novel that there aren’t any kids in them? Or for that matter any disabled people, old people, or sick people? It’s a grownup world where you’re either brilliant and yearn to be free from the shackles of petty people trying to repress your innovation, or you’re one of those petty people.

But actually our world isn’t like that at all. We have a community of humans, and like it or not we each contribute to our culture and do our part in defining success or failure.

I always like to point out that I hate laziness, and I have no patience for laziness. It’s a distraction to talk about how lazy whiny entitled kids expect us to pay for their college and then also expect to be given a cushy job afterwards (because libertarians tend to start talking about such symbols of what is wrong with social programs).

Even if there are examples of such people, there are plenty of other examples of people who genuinely worked hard but needed to take out lots of loans and didn’t understand their terms and now are desperately looking for work but can’t find anything. If the conversation is going well I’ll even talk about how if, as a culture, we are raising a generation of entitled kids (which is an exaggeration), then maybe it’s our fault and not the kids’ fault. Because it is.

The meritocracy myth

Jack and Larry

Recently a Wall Street Journal article described what I’ll call a “Larry Summers” moment for women in business. Namely, Jack Welch, the former CEO of General Electric, spoke to a bunch of women about how if they work hard enough they’ll be appreciated and get ahead. From the article:

He had this advice for women who want to get ahead: Grab tough assignments to prove yourself, get line experience, and embrace serious performance reviews and the coaching inherent in them.

“Without a rigorous appraisal system, without you knowing where you stand…and how you can improve, none of these ‘help’ programs that were up there are going to be worth much to you,” he said. Mr. Welch said later that the appraisal “is the best way to attack bias” because the facts go into the document, which both parties have to sign.

Just as in the case of Larry Summer’s now-famous 2005 speech about women in science and math, a bunch of women left Welch’s talk in frustration.

There is no such thing as a meritocracy

Having been in academic mathematics and a quant in a hedge fund, I’d guess I’ve experienced what comes closest in many people’s minds as the closest to a meritocratic system. But my experience is that it’s anything but, even in these highly quantitative settings.

Instead, as it probably is everywhere, the job environment is a huge social game where it matters, a lot, what kind of priorities you demonstrate and what kind of other signals you give off or respond to. We don’t expect people to play golf and smoke cigars in academia but caring about teaching, or worse, getting a teaching award, can be the kiss of death.

I’m not saying that your personal efforts don’t matter at all, because they do, and you do need to produce stuff, and at a certain rate, but even “personal efforts” are first of all received in the context of a social order (i.e. the perceived importance of your efforts at the very least is a social invention), and second of all they’re are not really personal – one frames the questions one answers with the help of the community, so it’s important you have a good connection and social acceptance in that community (i.e. access to the experts).

Business in more generality is even less meritocratic- there’s a specific requirement that you must “play well with others,” which is absent from academics (mercifully). This means that instead of being an implicit social game, it’s been made very explicit. This is where people promote their work, take credit for others’ work, learn to say what people want to hear, etc. The performance review is a circle-jerk event for such empty-headed manipulations, which makes it particularly ironic that Welch suggested women take the criticism in an appraisal so seriously.

In my experience, it is unbelievably useful for these social games to have an alpha personality, which just kind of means you assume you’re in charge even when it’s not explicitly a situation where someone’s in charge. People respond to such personalities on a chemical level and there’s really nothing a so-called meritocratic system can do about that.

In other words, I’m not holding my breath for a truly meritocratic system. It’s just not what humans evolved for. Let’s acknowledge that and work on how to make the system responsive to good ideas anyway (whatever the system is).

Successful people want to believe that there is such a thing as meritocracy

This begs the question, why do people like Jack Welch and Larry Summers hold on so tight to the myth of meritocracy? My theory is that it serves a two-fold goal: as advertisement for new people and as a validation of the winners in the system.

People want to feel like they are entering a level playing field then the best thing you can do is advertise it as a meritocracy, because it’s human nature to think that you’re better than average. So everyone wants to enter such a field, assuming they will rise to the top.

At the same time, the `winners’ of the social game want desperately to think they did amazing stuff in order to be so successful. They hold on to the myth of meritocracy as a religious belief, and it is pure dogma by the time they reach upper management. This plays into another part of human nature where we discount luck and the infrastructure that led to our success and take it as a sign of our personal choices. Lots of people in finance in general suffer from this diseased mindset but actually anyone who is high enough up in their respective `meritocratic system’ does too.

That’s my simple explanation for why these guys can go in front of a bunch of women and be so unbelievably tone-deaf. They are true believers, because their entire egos are built on this belief, and it doesn’t matter how much counter-evidence is presented to them, even in the form of humans in the room with them.

One last thought. If I saw people leaving a room in disgust when I was giving a talk, I imagine I’d be slightly aghast- I might even pause and ask them what’s wrong. But I guess that’s because I’m not alpha enough.

Powerpoint kills me from within my soul

If you are anything like me, the beginning of a meeting where there are powerpoint slides is physically painful. I’m a napper, too, so especially after lunch, the urge to put my head on a conference table and start snoring is overwhelming.

Because I know what’s going to happen.

Namely, there’s gonna be waaaay too much stuff on each slide and there’s going to be a speaker who is really proud of their soul-wizening presentation.

My eyes glaze over when there are sub-bullets and small fonts, and especially when the slide is sectioned off into subslides.

Why is this allowed to happen?!

People. If there are more than three ideas in your slide, that’s too much. If there’s more than a title and three phrases, that’s too much. If any of your phrases is longer than the line and wraps around, that’s too long, and your font should be really big so everyone can read it.

My preference is to have exactly one phrase on each slide. Otherwise everyone in the room is reading shit the speaker hasn’t gotten to. Except for the people pretending not to be asleep, who are totally disengaged and/or praying to die.

Get overpaid so people will listen to you

Have you read the recent article in the New York Times about how lower-status monkeys are less healthy and more stressed out than higher-status monkeys? Their gene expression actually responds to changes in social status. Does this resonate with your experiences with humans?

It does with me, and for us people I’d rephrase it this way: your concerns and ideas are given attention in direct relation to your status. Your stress levels rise as you realize your status is lower and your risks have grown.

Here are some examples from work. I’ve been disappointed to notice, time after time, that my ideas are considered important and innovative in direct proportion to how much they are paying me to have them. If I’m underpaid then nobody thinks I am all that smart; nevermind being a friggin’ volunteer (with some exceptions, but don’t stop me, I’m on a roll). This perversely makes me want to get overpaid just so I’ll get listened to.

Cuz why? Didn’t you ever notice that overpaid people’s ideas are about as good as anyone else’s but they are framed as pure brilliance? I have. It even works head-to-head: two people of different status come up with the same exact idea but the one who is more important was listened to and their idea championed. Oh yeah, I’ve seen it, and so have you (example: when I was at D.E. Shaw, we rated other people’s ideas with a “probability of success” in an effort to estimate their expected payouts; someone once showed me their idea, which was identical to one of Larry Summer’s ideas, but had come 2 years before and had scored about half as well. But my fried wasn’t an MD making $5 million per year so clearly his ideas weren’t as good!).

A similar thing happens with problems rather than ideas in a workplace. The worst examples of over-worked and under-appreciated situations clearly don’t happen at the top. For example, when I worked at MSCI, it seemed like the sales guys, who defined the top there, spent more time strutting around making sure each and every one of their efforts went appreciated than doing the actual efforts, whereas the lowly dev-ops guys, and the guys setting up the initial portfolios for the new clients, were treated as an afterthought, only noticed if something went wrong. They’d stay up all night fixing something, probably someone else’s mistake, and nobody would even thank them.

[It still seems so ironic that the most technical people there are also the least appreciated, since the product is essentially technical expertise. Or is it? Maybe I’ve got it wrong, and it’s really about selling technical expertise in a package that makes people feel safe and pious. Maybe the black box we’re selling doesn’t even have to work.]

If you are thinking that everyone at MSCI is in finance and is thus overpaid and pampered, then you’ve got it wrong, it’s a brutal atmosphere, like much of finance. If you don’t believe me, read my friend Katya’s blog, Left with Balls, where she talks about the spell of Wall Street.

Taking one step back, this kind of thing strikes me as unfair and frustrating. The idea that the lowest-ranked also has to deal with ridiculous stress and chronic health problems does not jive with my inherent concept of justice. Although it does seem like a natural response to a system that’s already been created (as in, as a consequence of being frustrated because my ideas are ignored, I want to get overpaid to get listened to, so I’m joining in on the perverted game and furthering the system), it doesn’t seem like we’ve done a particularly good job setting up these systems.

For a country that putatively considers itself a democracy, we seem to have a tremendous amount of respect for a rat-race corporate hierarchy. Is that a contradiction? Or is the American dream actually to start a hierarchy and to sit at the top? Do other people identify with the guys on the bottom or the guy at the top? Or the guys in the middle clawing upwards?

Question: is it really impossible to listen to and evaluate ideas based on their merit? How about anonymous polling of problems? It’s certainly technologically feasible, but we don’t do it.

Question: Is it really impossible to appreciate people who make things work behind the scenes? How about we ask people to sit with other people in entirely different departments in a rotation to witness what other people actually do? I really think that would help with the appreciation problem (but not if the technical people in your company are in India and the salesguys are in New York).

For the record, when I start a company I’ll do these things. Of course, I’ll be sitting up there at the top thinking what a great idea I had to do them.

In which mathbabe becomes insurance claims adjuster

Who knows what I’m talking about with this story.

My husband dislocated his finger sledding with my son last January, so more than a year ago, and the hospital kept sending us bills for the event.

But here’s the thing, we were covered under my medical insurance, which had perhaps recently changed policy numbers when MSCI took over Riskmetrics. So probably what had happened was my husband had given them the old insurance card, but in any case, in the the end I knew I wouldn’t have to pay since we’d definitely been covered.

The hospital called once a month or so, and every time they got hold of me I argued with them and told them to check their records. They kept telling me that the insurance company was refusing payment under any of the policy numbers I gave them.

In the end, last month, I called up the insurance company myself and got them to admit payment, which wasn’t hard since they said they’d already paid for the X-ray from the dislocation on that date. I called up the hospital and straightened it out.

So yeah, I ended up doing their job for them, and that’s both annoying and exciting because now nobody thinks I owe them $2400. In fact I did a victory dance (at work, because you always have to do this during work hours for people to answer the phone).

But why I’m writing about it today is that it’s actually really infuriating how often something like this happens, and I can’t help noticing that I always get out of it but many people wouldn’t. I’m at a huge advantage in this common situation because:

- I worked as a customer service person so I know how to talk to customer service people. Turns out you should always be polite, but never hang up the phone until your problem is solved. Just keep asking, extremely nicely, things like, “Hmmm… that’s confusing, what do you think could have gone wrong?” or “What would you do if you were me?” or if those don’t work, “Do you think you could tell me who to talk to sort this out? I’d really appreciate it.”

- I am always covered by insurance, so I never worry that they are right. This is an enormous advantage over people who sometimes lose coverage between jobs or something.

- I keep all my old paperwork. Impossible for people who don’t have an incredibly

boringstable lifestyle like mine. - I have a job that allows me to make calls like this during work hours. Obviously huge.

- I am completely unafraid of forms and red tape. This comes from experience, but I know most people are afraid of such stuff, and that alone would probably keep most people from arguing.

I really do feel like I am relying on my professional skills in order to get my insurance to pay for setting my husband’s dislocated finger, when that should be a no-brainer. If you are inexperienced and poor, you’d probably be completely at a loss for how to deal with this situation.

I wonder how many people have their credit scores lowered by medical claims which should have been paid but weren’t due to crap like this. It’s a broken system, but it only leaks on the most vulnerable people, and I hate that.

Thought experiment: witness protection program

I’m often accused by my family members of having no imagination.

I really don’t think that’s fair, I think it’s more that they have outrageous amounts of imagination, and I’m normal. My husband will say something at the dinner table along the lines of, “hey I was thinking about what it would be like to live on a planet that’s attached to another planet by a weird system of ropes,” and without skipping a beat one of my sons will start asking questions: “Are they going straight up in the air or slanted? Can you climb up to the other planet? How far away is it?”. Pretty soon they are, and I’m not kidding, arguing about how thick the ropes are and the question of traveling between the planets and the different civilizations that would evolve on these two conjoined spheres. I’m an observer.

When one of them says something directly to me along the lines of, “mom, what if we lived on a spaceship going to Mars and we could only eat a liquid diet and there were no books, only videogames?”, I am usually pretty stumped (fake example, I just made it up, but you get what I mean). It just doesn’t make sense to me, and I’m constantly going back to one of the assumptions and asking why – why no books? Can’t we get books if we have so much technology? This is when my kids roll their eyes and walk back to their room.

I can’t help it, I’m just a practical-minded person. I want to solve problems but I want those problems to make sense.

In pure defense of my own ability to imagine, I came up with the following thought experiment. For some reason, which doesn’t matter (although it can be fun to come up with ridiculous reasons), we are all put into the witness protection program, and have to move to a tiny little town in the south or the midwest and we have to blend in with the townspeople, and figure out how to make a living and how to make a home. Or at the very least, if we don’t blend in exactly, we have to come up with a good story to explain our eccentricities, and it can’t be, “we’re in the witness protection program!”.

The first question is how we can make a living. I usually imagine waitressing at first, then learning how to be a car mechanic. I think of being a car mechanic as the coolest, nerdiest thing you can count on being able to do in a small town. Plus I love those jumpsuits with the grease stains, I would totally rock my jumpsuit, kinda like these guys:

My husband is a bit harder to place. He’s kind of a huge math nerd, with no actual practical skills, so the best we’ve come up with is that he can be the guy who goes around to people’s houses and helps them with their computer set-ups. But as people are getting better at computers, and as wireless systems are getting easier to set up, this plan is becoming increasingly weak.

Then there’s the issue of his Dutch accent. The idea that our story is that we’ve just moved like 60 miles, so we’re supposed to be heartland Americans, and the accent totally messes up that story. Sometimes (in my mind of course) I make him mute, other times we explain it with some weird speech impediment or maybe a stroke. I know it’s ridiculous, but it’s a toughie!

Finally, there are my kids. They are going to have to play along with the story too, but the problem there is that they’ve been raised (intentionally) to be pretty smart-assed. I’m trying to imagine them going to some random school and not giving away that they’re from Manhattan, watch the Colbert Report every night, and have strong opinions about the GOP race (and those opinions are not positive). Put on top of that the atheism thing, and I’m getting worried. I haven’t spent enough time in little towns (say, in Iowa) to really know how weird that would be, but I’m guessing pretty obviously not-from-around-here weird.

This is one of my favorite dinner topics, I suggest you try it.

What is innovation?

I’ve come to pretty much despise the word “innovation.”

First of all, it’s painfully overused, whether you work in finance or a start-up.

In finance, when people complain that banks and hedge funds should be regulated because they take dangerous risks that they don’t understand and that taxpayers have to backstop, the response, typically from a chorus of business professors and economists, is “don’t over-regulate, you might stifle innovation!”

Never mind that if you dig down to what is meant by financial innovation, it usually consists of creating weird mathematical instruments or contracts that require a complicated computer algorithm to price. So, pretty much the stuff that gets us into weird messes in the first place.

If I needed to write a sign to sum this up, it would read something like “Please stifle financial innovation!”. Actually, Volcker said it best: “the only useful banking innovation was the invention of the ATM.”

As it’s used in start-ups, the word “innovation” is also mostly painful to experience. For the most part it’s baldly used as a buzzword, by someone with a spiffy presentation who is clearly not himself (or herself, don’t want to be sexist) planning to be innovative.

In such a buzzword context, innovation becomes meaningless. At best, it’s their attempt to encourage and cajole the people around them to be innovative, and then perhaps take credit for such innovation. At worst, they fetishize Steve Jobs, which usually means channeling his perfectionist asshole side, thinking that may spur extra innovation.

What’s particularly sad about the abuse of this word is that it is inherently meaningful, and that I see and read about true innovation every day, mostly gone unnoticed by the spin doctors. Maybe that’s because most of it is too technical for business guys to get their heads around.

Another thing I’ve noticed, is that usually the most innovative people are also the most high maintenance pain-in-the-ass people to work with. Sometimes (often) downright hostile in fact.

I’ve come to enjoy this phase of “creative hostility” as a way of getting through skeptical or openly suspicious questioning incredibly efficiently. If I propose something and my most innovative, hostile critics immediately jump down my throat, that’s a sign my idea was a good one. I know that sounds weird but it’s true.

Actually maybe it’s not so weird. I watched this TED talk by Brene Brown where she talks about shame, vulnerability, and innovation. You should watch it, it’s only 20 minutes and it’s good.

Specifically, she talks about how, in order to be innovative, one must make oneself vulnerable. Even though she didn’t have time to really argue this, it resonates with me. The most innovative moments I’ve experienced are when everyone involved is willing to be wrong (vulnerable) and to smell each other’s bullshit (skeptical). Opening yourself up to other people’s skepticism takes courage.

She also describes how cultural norms can come into play at moments of shame or vulnerability or courage. In particular, this thing where men cannot be seen as weak. I think it explains why, when I see innovation, I also tend to see overt displays of macho behavior.

I wouldn’t have it any other way. I say that because I’m pretty sure the alternative is passivity and indifference, which is totally unappealing.

Here’s what I think. Real innovation is a mess and brings up all sorts of things that people don’t actually want to talk about. That’s why we only hear about some watered-down a posteriori description of it.

Parents: don’t put your kid on a diet

Yesterday I read this article about a mother, Dara-Lynn, who put her daughter Bea on a diet, tiger-mom style, and then triumphantly wrote about it in Vogue, and more recently got a book deal. This brings up lots of stuff for me personally, and I think it’s time for me to write about it.

First of all, I would like to address the issue of why people care so much about parenting issues in the first place. I mean, I guess if you aren’t a parent and don’t plan to be one, this doesn’t matter quite as much (even though you of course were yourself parented, so it should still be somewhat relevant).

My message is basically, don’t dismiss parenting discussions- they expose who we are and what we aspire to be as human beings. Questions of how we parent and what values we choose to impose on our children, who are of course vulnerable to such things, are question of how we individually form and inform culture, creating a tiny piece of the larger culture inside our homes. As parents we want to both affect that culture and prepare our children for the larger world, and it’s a tricky balance.

So given that, what values are we imposing on our kids when we put them on a diet? I can infer that somewhat from the article but I can also speak from personal experience, because my parents put me on a diet when I was 10. My parents set up system whereby I’d be punished (by losing my allowance) if I didn’t lose at least a certain amount of weight each week. They also explained to me how calories worked. That’s it. They let me loose with that information and ultimatum. (ooh, just remembered: the reward for losing 5 pounds was, ironically, a candy bar.)

It was a little strange, in retrospect, for a few reasons. First, I had been chubby since soon after birth. My parents are both and were both chubby. My grandmother lived with us off and on and constantly hoarded bags of candy and fed them to us constantly while watching soap operas. My older brother was also somewhat chubby. In spite of this, I was the only person on this regimen, and nothing else about our eating habits changed besides that I was expected to keep track of the calories I ate- the food itself was still hamburgers, boiled vegatables, and spaghetti with butter.

I guess this may have been my first experience dealing first-hand with a misleading, pseudo-quantitative model. I was told by my parents that losing weight was a simple concept of calories in and calories out, and thus must be simple to deal with. I was honestly too young to question this, and to also question why they hadn’t achieved their perfect weights if it was so simple.

Now, to the question of values. From my perspective as a kid, the values I learned were the following:

- I am terrible at following simple directions, because I can’t seem to control my eating,

- I don’t look good to other people, and

- it’s really important to look good to other people.

All in all, a pretty nasty set of values that I carried around with me like a sin for years, until something else happened, which I will get back to soon.

You might say that the article with Dara-Lynn and Bea is completely different, because first of all the mother wasn’t offhand in planning her daughter’s diet: she lived and breathed the control that she thought was required to get her daughter to lose weight. Also, it was a “success,” in that Bea lost the weight her mother set out for her. Even so, I see parallels for Bea’s received wisdom from her mother:

- You have to submit entirely to someone else (me, your mother) because you can’t be trusted to follow your instincts,

- You didn’t look good to other people, and

- it’s really important to look good to other people.

But I do feel sorry for her on top of what I went through, because now her mom is not only in a national magazine bragging about her control over her kids, she’s also gotten a book deal to go into the details of this control freakiness. Because it’s all about how a mother can foster good eating habits in her kid. I guess.

If there was any justice in the world, it would be Bea getting the book deal, in advance, to describe what it’s like to live with such a control freak mother. I honestly wish her luck.

A few concluding remarks. First of all, if you were wondering when the nerdy stuff was coming, here it is: there’s enormous selection bias going on. For every mother you hear about who drags their kids kicking and screaming through a diet, there are hundreds of poor kids who ended up like me, with failed enforced diets and incredibly guilty consciences (but at least no pictures in Vogue of their shame). We don’t hear about them, of course, because nobody wants to.

Next, although Bea is a “success story” now, I’m pretty well versed in statistics on teenage dieting and I’m anticipating lots of terrible experiences for the daughters of the women who will buy this book. A generation of girls who are ashamed and self-conscious.

Finally, how I got over my shame. It was mostly a coping mechanism. I went into a hospital when I was in 10th grade, with deep feelings of depression, and missed a few weeks of school. It was a critical moment for me, and I knew it. I had to decide whether to be depressed and passive for the rest of my life or whether to try to live life on my own terms. I basically decided to take on the following “anti-values” in order to obviate the terrible self-image I harbored at that time. I came up with these three anti-values, which I still live by:

- I forgive myself for not being good at controlling myself, because I love my body, even parts of it that confound me,

- I look good to myself, and

- it’s not that important to look good to other people.

Probably not stuff for a book deal, but at least it’s kept me from giving my kids eating disorders.

How informed does an opinion have to be before it’s taken seriously?

How informed should an opinion have to be before it’s taken seriously?

I’m kind of on one end of the spectrum here. I would argue that you only need to know enough to get it right.

The original power of Occupy for me is in the following sentiment: you don’t need to understand the system’s insides and outs in order to know the system is screwing you. Of course it’s a different thing to fix something, but let’s leave that aside for the moment.

So, if you are a student with $80,000 in loans, a degree, and no job prospects, and all your friends are in the same or similar situations, then you can fairly say that the system is broken. And you’d have a powerful argument. The beauty of this argument, in fact, is that you and your friends provides living examples of how the system is broken, and defies all expert opinion to the contrary.

And one thing that we have had enough of lately is expert opinion.

This question came up at a recent Occupy Wall Street Alternative Banking group meeting, and not for the first time. The context was the collapse of MF Global, and we were talking about tri-party repos, which have intermediaries, and (maybe) fiduciary duties, and various questions arose over the legal issues as well as the question of whether Corzine et al had yet been asked these questions by Congress.

The details don’t matter. The point is, it’s complicated, and the question came up whether we had to know absolutely everything in order to be seen as asking an informed opinion and in order to be taken seriously.

Now, it’s a good idea for us to know the basics: the parties involved, their relationship to each other, and especially their individual incentives. But on the question of knowing if a specific question has been asked before, I think that doesn’t really matter. The truth is, we are some of the wonkier people in financial matters, and if we don’t know about it, then probably most people don’t.

And moreover, since we are trying to figure out how to represent the average person in such situations, that’s a good enough test. In fact, even if a question has been asked, if it hasn’t been adequately answered for the sake of the 99%, it’s still fine to ask and ask again until we have a satisfactory answer.

I’m all for being informed myself, and I like informed debates, but I don’t want to get stuck in some “cult of expertise”, where I think nobody is allowed to have an opinion unless they are incredibly well versed in something, especially when the underlying issue is actually one of ethics and justice.

Think about it: such thinking gives experts an incentive to make things more complicated in order to exclude non-experts. In fact I’d argue that such a “cult of expertise” incentive does in fact exist, has existed for some time, and the result is our financial system, tax system, and legal system.

It’s bullshit. We need to allow people who know enough to get it right, and have skin in the game, to enter the debate, and be heard, even if they don’t know the intricacies of the legal issues etc.. Those intricacies, likelier than not, have been partially put in there to confuse the very people the system was putatively set up to serve.

I regret nothing

There are a few parts of my brain that are missing. I know this not because I used to have them, because I didn’t, but because of how other people refer to their own feelings and thoughts, which I simply can’t relate to or sometimes even decipher.

One of them is the part of the brain that enjoys art. I already explained how I don’t like or understand paintings. I just don’t get why people look at art. The closest I can get to enjoying art is photography, and then usually I only like naked photos. But at that point I don’t think it’s liking it for the artistic part exactly.

Here’s another confession. I don’t have a regret center in my brain. I am someone who regrets nothing. I mean, every now and then I certainly realize I made a mistake, and I do experience an “oh shit!” feeling that I made that mistake. Like, I’ll get in the wrong line at a check-out counter and the other line will go faster (“oh shit!”). But that doesn’t seem to compare with other people’s concept of regret.

Here’s how I argue that nobody should experience regret. Let’s assume you a regret decision you’ve made, that you later believe you should have made differently. But when you’re faced with a choice, there are things you can control and things you can’t. There are things you know and things you don’t. There are consequences that you can measure and those you can’t. You do the best you can with the information you have when you make your decision. Then it’s done. What’s to regret? If you went back to that place and that time, knowing what you knew then, and being that person you were then, you’d do the same thing. It’s kind of a tautology, but it’s convincing to me.

Maybe you are mourning for not being a person who could have made a different, better choice? Even so, (I’d suggest), don’t be regretful about that, but rather try now to become someone who would make the right decision next time.

What is the utility of a regret? Does it help us do better next time? I’m all for learning from mistakes, but I don’t see why it should be such a negative process. Maybe I learn more slowly from my mistakes because I don’t have regretful feelings.

On the other hand, from my observation of this alien emotion, I’d argue that the fear of having future regrets is more of a problem than the possible mistakes people actually make. That fear seems pretty unpleasant and it seems to cloud people’s decisions: they end up experimenting less and taking fewer risks.

Am I missing something? Since I can’t understand regretting, I probable am, so please explain it to me.

The higher education bubble

Yesterday there was a Bloomberg article that explained how badly students understand their student debt. It occurred to me reading this, and not for the first time, that students are really the perfect choice of victim for the educational financing machine: they are typically naive about money, and a combination of incredibly hopeful and incredibly thoughtless about their futures – if they think about the future at all, they project themselves to be as successful as some chosen role model, against all odds. I was lucky enough to go to a state school which my parents could afford and were willing to pay for, graduating in 1994, but looking back I would have signed away on whatever dotted lines if I’d been asked.

Students don’t think to shop around for a better deal, or even bother to understand the deal they’re in. What’s the incentive for good deals in these circumstances?

More generally, the existence and price of college itself is a perfect trap for students. It’s been a growing assumption in the past few decades that one needs a college education to get a good job, and certainly in a poor job market like the one right now that is certainly true. And yet, the student debt load is increasing faster than the opportunities higher education provides.

We are just now finally seeing a “market reaction” to the outrageous costs and relatively meager returns on law school education. For example see this recent New York Times article, which I found through Naked Capitalism (and which also gave me the title for this post).

My mother and I were recently talking about Occupy Wall Street protesters and student debt. She’s been a professor in computer science for more than 40 years, and explained how she sees it:

Academia expands for students and gets subsidized by all the loans to them, without regard to what the society actually can accommodate.

So not only are students fed the line that they have to go to college, no matter the cost, and whatever the resulting debt, but they then go to college and end up with majors and/or knowledge that is actually not needed or useful to them or anybody else when they graduate.

In a given individual situation, you can always sort of blame the choice someone makes- why did you major in that at that over-priced college with that outrageous private loan? Did you really think you’d be a hot item on the job market?

But when you step back and look at this system, it’s maddening. We are essentially forcing, as a rite of passage to adulthood, each generation of our young people to go through a process which leaves them with ever more questionable skills and saddles them with an ever-increasing debt burden. When you add to this that fewer and fewer jobs are willing to train people while paying them, the advantage that a wealthy young person gets from having no debt and being able to intern for free means this system is also increasing inequality.

I understand that professors don’t like to think of their departments as businesses, and I am not someone who wants to corporatize academics in the sense of wanting departments to prove their business models by producing revenue streams or winning grants just to stay alive. But at the same time we’ve got to do a better job with this overall and help give our younger people a better chance.

Update: apropos article from Bloomberg just published here.