Archive

Happy Birthday to me!

The mathbabe blog is one year old today. I want to thank all of you guys for making this such a wonderful and thoughtful year for me. I totally love and adore you readers, and commenters, and guest bloggers, and yes, right now I even have room in my heart for you trolls.

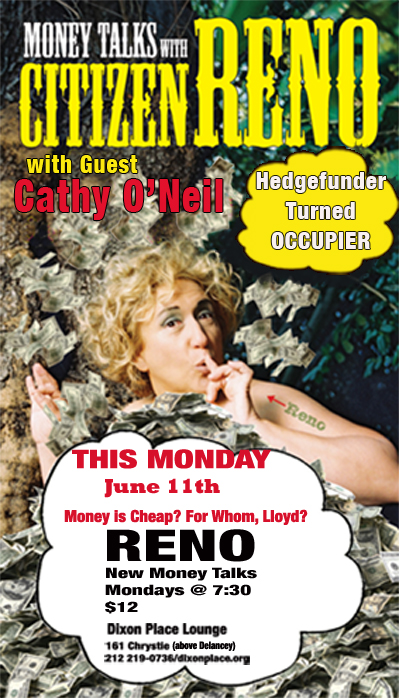

Tonight I’ll be performing again with Reno, which promises to be a hoot. Please come!

A low Fed rate: what does it mean for the 99%?

I’m no economist, so it always takes me quite a bit of puzzling to figure out macro-economic arguments. Recently I’ve been wondering about the Fed’s promise to keep rates low for extended periods of time. Specifically, I’ve been wondering this: whom does that benefit?

[As an aside, it consistently pisses me off that the people trading in the market, who claim to be all about “free markets” and against “interference” from regulators, also are the ones who whine for a Fed intervention or quantitative easing when bad economic data comes out. So which is it, do you want freedom or do you want a babysitter?]

Here’s the argument I’ve gleaned from the St. Louis Fed’s webpage. When the Fed lowers (short-term) rates, it makes it easier to borrow money, it makes it easier for banks to profit from the difference between long-term and short-term rates, and it potentially can cause inflation (and bubbles) since, now that everyone has borrowed more, there’s more demand, which raises prices. And inflation is good for debtors, because over time their debts are worth less.

One thing about the above argument stands out as false to me, at least for the majority of the 99%. Namely, many of them are already indebted up their eyeballs, so who is going to give them more money? And what would they buy with that money?

In other words, if the assumption is that everyone is getting easy loans, I haven’t seen evidence of this. Wouldn’t we be hearing about people refinancing their homes for awesome rates and thereby avoiding foreclosure? How many stories have you heard like that?

If not everyone is getting easy loans, and if in fact only the 1% and banks are getting those gorgeously low-interest loans, then it’s not clear this will be sufficient to spur demand and cause inflation. And inflation really would help the 99%, but only of course if wages kept up with it. Instead we have not seen high inflation and wages haven’t even been keeping up with what inflation we do see.

So let’s re-examine who is benefiting from low Fed rates. I’m gonna guess it’s mostly the banks, and a few private equity firms that are borrowing tons of money to buy up great swaths of foreclosed homes so they can turn around and profit on renting them out to the people who were foreclosed on.

I’m not necessarily advocating that we raise the Fed rates. But next time I hear someone say, “low Fed rates benefit debtors” I’m going to clarify, “low Fed rates benefit banks.”

How to talk conservative

I finished reading “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion” and I have to say, I got a lot out of it. Even if they are just approximations to the truth, it’s interesting to consider his various positions. Near the end he talks about religion and “groupishness,” and how people are too focused on the technical aspects of religious beliefs rather than what a religion accomplishes in a community, which he claims is its main benefit.

But what I found more interesting is the beginning of the book when he discusses the different moral make-up of liberals and conservatives (and libertarians) in this country. Namely, he claims that liberals care primarily about the following three things:

- caring for the vulnerable or victimized,

- the concept of oppression from bullies – or conversely the concept of liberty, and

- the concept of proportional fairness (you deserve a part of the pie since you helped make it, but you wouldn’t deserve any if you hadn’t helped).

By contrast, conservatives care about a larger set of six things, the above three as well as:

- the concept of sanctity,

- the concept of authority – when it’s just and those in power take proper responsibility, and

- the concept of loyalty.

I took away three points. First, liberals are bad at guessing what conservatives think, because they are somewhat blind to these last three things, and when they see conservatives go on about them, they assume conservatives don’t care about the first three, which is wrong, although it’s true that they care about them differently (especially proportional fairness: whereas liberals emphasize leaving nobody out, conservatives emphasize not letting people get extra, especially if it comes from their stuff). Second, if I, as a liberal, want to communicate with a conservative, I have to talk about all six of these with some level of understanding. Finally, statistics and other rational arguments only work if the person you’re talking to already agrees with you or if they are exceptionally open-minded – in any case you have to appeal to their morals before going into stats.

With that in mind, here are two rants against the Stop, Question, and Frisk policy, one written for a liberal audience, one for a conservative audience.

Liberal version First, the stop, question, and frisk policy targets minority men almost exclusively. Second, almost 90% of the events end up without an arrest, which means it’s unwarranted intrusion and bullying- typically the reason given for the stop is a “furtive movement”, which could be absolutely anything. Finally, there is a quota system in the police department which forces each officer to perform these unwarranted searches whether or not there is cause, which inevitably leads them to target the “least likely to complain,” namely young, poor minorities. We need to stop the police abusing their privileges in this way immediately.

Conservative version What is the difference between a police force and a gang of men who walk around with guns? The answer, in the best of worlds, is authority, intentionality, and the rule of law. Police have an important job to do, which is to protect us, and to keep the streets safe. And when they do a good job, we admire them for that and count on them for their protection. But imagine if, instead of seeing your neighborhood cop as someone you can count on, he instead consistently stops you on your way home from school or work and asks you suspicious questions, and sometimes even takes your keys from your pocket, and, while you’re locked in the police car, enters your apartment and terrorizes your family. This makes you feel like you are the bad guy, even though you did nothing wrong. After a while, it would make you and your neighborhood less trusting of the authority of the cops, which would lead to reckless behavior and lawlessness, because your rights are no longer being protected. We need to stop the policy of Stop, Question, and Frisk in order to make sure the police never become just a bunch of bullies with guns.

Biking in New York City

I’m a huge fan of biking around the city. I like to commute to work, from the Columbia University neighborhood up at 116th and Broadway to just below Houston on Varick. Since both my house and my work are within blocks from the west side of Manhattan, I can bike the whole way along the west side bike path (see, for example, this map).

It’s a gorgeous ride along the Hudson River, and there’s not one day I ride it without appreciating not being stuck in the traffic next to me on the West Side Highway. Okay, actually, last Monday was one, when I got caught in a huge thunderstorm. Luckily I had dry clothes, but for some reason no dry socks (note to self: bare feet with wet leather boots is gross). I’m also happy not to be on the subway (1 line) on Monday mornings when people are extra grumpy about going to work.

I don’t bike when it’s (already) raining, or when it’s icy, and it’s always a bummer when daylight savings starts, because it means it’s already dark by the time I leave work. But otherwise I am on the lookout for great biking days and opportunities.

A few weeks ago, on the first really gorgeous day of spring, I biked from one Occupy meeting to another, the first one up at Columbia and the second in Union Square (to see my friend Suresh Naidu speak about Radical Economics 101). I biked through Central Park, which was bursting with spring joy, and then all the way to Union Square down Broadway, which now has a beautiful bike lane. The only annoying part was Times Square, which is so full of tourists you have to walk your bike. So that’s a good sign, when the pedestrians are more dangerous than the cars.

And I also bike on other streets, although after being doored a few times and breaking someone’s windshield with my head (a long time ago in Berkeley but still) I am hugely defensive- I pretty much assume every moving car is trying to hit me and every parked car’s door is about to open. Even so, there are quite a few quiet streets I can feel safe biking down, in the middle, and although it’s not very fast, it’s certainly faster than walking. A great way to explore the city.

And I’m not alone, here’s a great essay by David Byrne in a recent New York Times Opinion column entitled “This is How We Ride”. It’s a beautifully written piece, and he describes the joys of biking in the city perfectly. He mentions that there’s a new bike-share initiative starting this summer, where there will be 10,000 bikes for rent at 420 bike stations in Manhattan, Long Island City, and Brooklyn.

That’s awesome, even if I will have to share the bike lane with even more enthusiasts. The rides are limited to 30 minutes, so not a full commute for me, but it means that if I’m already downtown and want to get to the East Side (which is always hard – I like to say that going to the East Side is like going to L.A. in terms of logistical difficulties) I will be able to hop on a bike and cross town. Cool!

Everybody lies (except me)

There’s an interesting article in the Wall Street Journal from yesterday about lying. In the article it explains that everybody lies a little bit and, yes, some people are serious liars, but the little lies are the more destructive because they are so pervasive.

It also explains that people only lie the amount they can get away with to themselves (besides maybe the out-and-out huge liars, but who knows what they’re thinking?).

When I read this article, of course, I thought to myself, I don’t lie even a little bit! And that kind of proved their point.

So here’s the thing. They also explained that people lie a bit more when they are in a situation where the consequences of lying are more abstract (think: finance) and that they lie more when they are around people they perceive as cheating (think: finance). So my conclusion is that finance is populated by liars, but that’s because of the culture that already exists there: most people just amble in as honest as anyone else and become that way.

Of course, every field has that problem, so it’s really not fair to single out finance. Except it is fair to single out any place where you can cheat easily, where there are ample opportunities to lie and profit off of lies.

One cool thing about the article is that they have a semi-solution, namely to remind people of moral rules right before the moment of possible lying. This can be reciting the ten commandments or swearing on a bible, which for some reason also works for atheists (but wouldn’t stop me from lying!), or could be as simple as making someone sign their name just before lying (or, even better, just before not lying) on their auto insurance forms.

Can we use this knowledge somehow in setting up the system of finance?

The result where people are more likely to lie when they know who the victim of their lie is may explain something about how, back when banks lent out money to people and held the money on their books, we had less fraud (but not zero fraud of course). The idea of personally knowing who the other person is in a transaction seems kind of important.

The idea that we make people swear they are telling the truth and sign their name seems easy enough, but obviously not infallible considering the robo-signing stuff. I wonder if we can use more tricks of the honesty trade and do things like make sure each person signing is also being videotaped or something, maybe that would also help.

Unfortunately another thing the article said was that having been taught ethics some time in the past actually doesn’t help. So it’s less to do with knowledge and more to do with habit (or opportunity), it seems. Food for thought as I’m planning the ethics course for data scientists.

Favorite bands

My 9-year-old’s favorite bands (and favorite songs):

- Queen (Bohemian Rhapsody)

- AC/DC (Back in Black)

- ABBA (Fernando)

- Green Day (American Idiot)

- Weird Al Yankovic (Canadian Idiot)

The modeling death spiral for public schools

There was recently a New York Times article about how the public schools have become super segregated by race.

I’m wondering how much of this can be explained by income rather than by race in combination with the obsession we all have with test scores. Let me explain.

If I’m living in a neighborhood with a neighborhood school and the school seems pretty good, then depending on how picky I am I might just stay living there and let my kids go there.

Now assume that suddenly there are test scores available for all the schools in the area, and it turns out my neighborhood school doesn’t do as well as a surrounding neighborhood. Then, depending on how much I think those test scores matter to my childrens’ futures, and how much resources I have, I will be tempted to move to that neighborhood for the “better schools” (read: better test scores).

Over time, people with good resources will move to the new neighborhood, which will become more expensive because there’s competition to get it, which in turn will make it easier for that town to raise local taxes to improve the school, and will also attract parents who really care about the quality of the schools, which will improve the school and presumably the test scores of that school, exacerbating the original difference of test scores.

And of course that’s just what’s happened in this country. My parents moved to Lexington Massachusetts for the schools, and they paid a premium for their house for the location and the school system. So I went to a public school but one that increasingly was attended by richer and richer kids.

Income segregated public schools are the new private schools.

In New York City, where there is more to consider than just your neighborhood, because you can get your kids into schools in other neighborhoods, and there’s a whole network of gifted and talented schools as well, it’s a much more complicated dynamic, but the underlying reasons are the same, and they again have to do with segmentation modeling: we know which schools do well on tests and we avoid poorly testing schools if we can.

The availability of the test scores is huge- if I’m thinking of moving to a new city I can just look up the SAT scores of the high schools in the area and try to find a place to live which is in one of the highest-scoring towns.

This is what I call a death spiral of modeling, and it’s the same idea I described here when insurance companies have too much information about you and deny you coverage because you need insurance so bad. And it’s very difficult to get out of a death spiral, because to do so you need to reset the whole system and re-pool resources but in this case people have already moved out of town.

Questions I am thinking about:

- Is it dumb to care so much about test scores? On the one hand I don’t want to take chances on my kids, so I will opt for the conservative route, which is to think they should be surrounded by kids who test well, because certainly in extreme cases that kind of thing is likely to be contagious behavior. But maybe we have exaggerated ideas about how contagious these things are or how important test scores really are to our kids futures. How would we test that and how would we disseminate the results? And what if we found out that everybody has been acting totally rationally?

- Which begs the other question, namely how can we get this system to work better overall for the average student that would be realistic?

- Note that in the above discussion I haven’t talked about the teachers at all, which is strange. But from my perspective, our system is all about concentrating kids who test well together, and it’s not all that clear that the teachers matter, although I’m sure they do actually. What am I missing? Is there a way of solving this death spiral problem through awesome teachers?

Conspiracy theorists may be right but they can’t explain why

I’m still reading Haidt’s “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion,” very slowly, because I have approximately 15 spare minutes a week set aside for free reading.

The part I read last night had to do with how we use our brain as a press secretary for what we believe, arguing for that policy using all the persuasiveness we can muster, no matter how weak our evidence is.

Specifically, if we see evidence for our point of view, we jump on it. If we see evidence against our point of view (oh shit!), we wrinkle our foreheads and feel stressed out, causing us to search and search until we finally find evidence for our point of view again (whew!).

This all seems right to me, although I may just be excited about it because it was already my point of view.

Haidt then goes on to explain that our pleasure centers are directly stimulated when we go through this process of confirming our view, especially when it was somewhat challenged by contrary evidence, and especially if our view is pretty hardline. Finally, he explains that conspiracy theorists are addicted to that pleasure center stimulation moment like a heroin addict.

Assuming this is correct, it explains something I’ve been super puzzled by with conspiracy theorists. And I should say that, being part of OWS, you get to interact with more than your fair share of such people.

Namely, they can never explain their position. In fact I’d say that this is their characterizing feature: one is dubbed a conspiracy theorist not by the unreasonableness of one’s position but by the way one tries to communicate it to other people. If you just had a strong opinion but could explain it well and persuasively, then you’ll never be considered a conspiracy theorist, although of course you could be considered an asshole (depending on what hardline opinion you harbor).

Example: when I try to engage my conspiracy theorist friends (because I do think they are for the most part dear people), they very often get into the tangential loops where they concentrate on one of the following:

- They don’t explain this to anyone/ it’s a secret

- It’s too hard to understand

- There’s a small group of people who have all the power

In spite of trying to convince them that you are listening, you are smart, and you understand that we don’t live in a perfectly fair system, it’s really hard (but not necessarily impossible) to get them to settle down and tell you why they believe these things. I think their pleasure centers must also get stimulated when they go over these three points, because as I said they get totally distracted and it’s difficult to interrupt them.

And by the way, they are willing to try to explain their theory to you. I think one thing Haidt forgot to mention is that it must be a huge thrill to convert other people to your point of view when you are a conspiracy theorist, because often that seems to be a very serious goal.

When it comes to our current financial system especially, I’m starting to believe that many of these points are overall valid, but it’s kind of tragic how poorly my friends explain them. Maybe part of my blog can be devoted to explaining the “why” of the conspiracy once I think I’ve got a good argument.

One last thing which Haidt mentioned and that I’ve noticed too (but which I’m wary of exclaiming as his key point since, again, I already believed it). Namely, scientists are trained to look at evidence and admit when they are wrong. In the realm of mathematics this is certainly so: if you see something disproved it’s a simple waste of time to keep thinking it’s true, even if you previously fervently believed it.

But of course this only holds in the context of theorems and proofs- I’m not sure mathematicians are any better than anyone else in admitting they’re wrong outside of the context of theorems and proofs. Haidt mentioned that there’s no evidence that moral philosophers are any more moral than other philosophers, for example.

How are you a narcissist?

A few months ago I took a narcissist test on Oprah’s website (see here). I scored exactly average overall, meaning I’m not a narcissist, or rather I’m exactly in the middle for the population for the narcissistic traits, but if I looked at the actual categories I didn’t score average in each category.

In particular, I maxed out in the categories “Authority” and “Exhibitionism” but scored quite low on “Vanity,” “Exploitativeness,” and “Entitlement”.

I think about says it all for why I blog. It’s because I love you all so much and want the world to be a better place, and I know exactly how it should be and I seriously need you guys to listen to me.

Innovation, elevation, and space travel

Science Fiction writer Neal Stephenson recently wrote this essay entitled “Innovation Starvation” on how it’s too bad we don’t have an innovative culture any more. I kind of like and agree with some parts his essay, especially this:

Most people who work in corporations or academia have witnessed something like the following: A number of engineers are sitting together in a room, bouncing ideas off each other. Out of the discussion emerges a new concept that seems promising. Then some laptop-wielding person in the corner, having performed a quick Google search, announces that this “new” idea is, in fact, an old one—or at least vaguely similar—and has already been tried. Either it failed, or it succeeded. If it failed, then no manager who wants to keep his or her job will approve spending money trying to revive it. If it succeeded, then it’s patented and entry to the market is presumed to be unattainable, since the first people who thought of it will have “first-mover advantage” and will have created “barriers to entry.” The number of seemingly promising ideas that have been crushed in this way must number in the millions.

It’s similar to my reasoning for not googling something under discussion for at least 30 minutes, especially when it seems possible to reckon whether it’s true or not.

I would add this: it’s tempting to immediately gauge the competition when you have a new idea, especially a business idea. But if you develop it within yourself or a small group of people it will inevitably morph into something that is probably unrecognizable from the original idea, so with that in mind, googling the original idea is actually irrelevant anyway. Stephenson makes a point similar to this in his essay.

Stephenson goes on:

The illusion of eliminating uncertainty from corporate decision-making is not merely a question of management style or personal preference. In the legal environment that has developed around publicly traded corporations, managers are strongly discouraged from shouldering any risks that they know about—or, in the opinion of some future jury, should have known about—even if they have a hunch that the gamble might pay off in the long run. There is no such thing as “long run” in industries driven by the next quarterly report. The possibility of some innovation making money is just that—a mere possibility that will not have time to materialize before the subpoenas from minority shareholder lawsuits begin to roll in.

Today’s belief in ineluctable certainty is the true innovation-killer of our age. In this environment, the best an audacious manager can do is to develop small improvements to existing systems—climbing the hill, as it were, toward a local maximum, trimming fat, eking out the occasional tiny innovation—like city planners painting bicycle lanes on the streets as a gesture toward solving our energy problems. Any strategy that involves crossing a valley—accepting short-term losses to reach a higher hill in the distance—will soon be brought to a halt by the demands of a system that celebrates short-term gains and tolerates stagnation, but condemns anything else as failure. In short, a world where big stuff can never get done.

While I agree that people, especially within the context of large companies or government, are too short-sighted, I think this view is overly negative. On smaller scale, and in smaller companies, people do definitely take real risks (and pay for them sometimes).

But this essay is really about “doing the big stuff” and that’s where I’ll just have to argue against it altogether. Stephenson, like many sci-fi writers, is totally into the idea of space travel and is deploring the fact that we as a nation have turned away from it because of its expense and because we don’t want to take huge risks with money and people. Unlike in the good-old days of the Sputnik Era.

But I’d argue that the Sputnik Era was really about the Cold War and competition with the Russians, not space travel. This nostalgia is misplaced, similar to how people talk about family values and how great it was in the 1950’s, while ignoring the outrageous racism, sexism, and homophobia that existed then. It’s a revisionist view.

I’m not saying nothing cool happened in order to get a man on the moon, because clearly lots of cool stuff did happen. I’m just saying it happened in the context of a very serious us-versus-them mentality, where we were actively afraid of being blown up in a nuclear war, and I for one am not signing up for that again just so we can work together better.

More generally, Doing Something Big almost by definition means making sacrifices on other projects, so it makes sense that people who benefit from the chosen project think it’s awesome but other people not so much.

Going back to space travel: it’s a funny subject for conversation. When people talk about it they often experience elevation, which is my favorite recently understood emotion, and it means they transcend their normal existence. This seems to happen to young people and science fiction fans especially when talking about space travel, can happen to people listening to music, and used to happen to a lot of people when listening to Obama’s speeches.

Having been born and raised around science fiction and space lovers, I get this, and I can even summon up the accompanying elevated trance at will. But I also get that the idea of putting a huge amount of our resources into space travel, when we still haven’t figured out how to consistently feed people here on earth, is not completely reasonable.

I’m not arguing for no space travel, because there’s definitely a place for the basic scientific research that gets accomplished in the wake of cool, ambitious plans. But to Neil Stephenson I’d say, buddy there’s a pretty good reason this isn’t happening, and it’s not just because people aren’t innovative.

What’s fair?

Lately I’ve been thinking about the concept of fairness and how our culture decides on what’s fair. I think lots of arguments I have with other people come down to the fact that we have fundamentally different opinions on what’s fair, so I think it’s useful to consider having that argument instead of whatever argument we were engaged in. By the way, this actually makes me like people more- it’s not that they are mean, selfish people, but that they have a different underlying theory of fairness that they are loyal to.

For example, I have met people who claim that the government should only be in charge of protecting ownership rights and prosecuting criminals and that it should stay out of every other realm. The question of how to help people out with student debt loans then is certainly moot until we first talk about whether government should “care” about helping people at all for any reason.

The question, stop, and frisk policy is an example of a policy that our local government has taken on that reflects our shared understanding of fairness; in this case, we care more about preventing crimes, so being fair to victims, then we do about the suspects of crimes.

Tax law is another issue where we, as a society, have decided what’s fair and made it into policy. The fact that these laws change drastically over time – the top tax rate of 70% just a few decades ago is a far cry from what we’ve been seeing recently – indicates that we also change our mind about what is fair depending on conditions.

I’m not saying anything deep here- we all know that things change, and we no longer spend time watching slaves get killed in an arena, because it no longer jives with our concept of justice (although the NFL can sometimes seem a bit like that). I’m just trying to differentiate, and have other people agree to differentiate, between the rules we’ve constructed, in the form of policies and laws of the land, and the underlying and evolving moral decisions that we make as a community.

One more example, because I think it’s a good one for thinking about fairness and systems of rules (again not new). Imagine we have 100 people working on a farm, making their living, and we introduce a technology that allows 1 person to now do the work that 100 people did previously.

On the one hand it’s in some sense fair to keep one person on the farm, someone who is skilled enough to use this new tractor or whatever it is, and lay off the other 99 people.

But in a larger sense we still have the same output, so the same number of resources, and 99 people out of work means 99 people don’t have access to those resources, which doesn’t actually seem so fair. In the best of worlds (a world of textbook economic growth) those 99 people would go find new jobs in new fields and we wouldn’t have to worry about them. But what if those new jobs don’t exist, or exist only for the 23 people who have some other technical skills? This is when the rules we have created really matter, and our reasons for them need to be weighed and discussed.

Can clouds think?

Sometimes I have trouble falling asleep. Especially if I’m riled up thinking about the newest stealth bank bailout, or wondering how to model rare, fat-tailed events, I’ll toss and turn, unable to get these problems out of my head.

Luckily I have a husband who is kind enough to tell me his stories at moments like these. I really appreciate his ability to draw out a story. He starts out slowly, and gets slower. He ends up at such a leisurely pace that I get completely distracted from my work-a-day concerns simply wondering what he’ll say next, when he’ll say it, or if he’s just fallen asleep.

It’s not just the slowness of the stories that do the trick, either, it’s also the content. He’s the master of the boring relaxing, abstract, science-fictiony story with exactly one idea. He’s seriously considering starting a blog for his stories which he’d call `Stories that put my wife to sleep’. I honestly think it would work great for lots of people- a public service, really, especially if he made very very very boring podcasts.

It’s efficient too, he’s mentioned to me that he’s told me the same story sometimes 5 or more times but I can never last through to the point of understanding the plot, and it always seems new. I never know what’s going to happen next, if anything.

My favorite story, which I have probably heard 17 times, is the story of whether clouds can think. It’s unresolved, the answer, but it’s wonderful to imagine, very slowly, the decisions a cloud could make, things like very slight changes in its luminosity or which winds to take rides on or how high to fly.