Archive

WTF: Greek debt vs. CDS

Just to be clear, if I’m a hedge fund who owns Greek bonds right now, and say I’ve hedged my exposure using CDSs, then why the fuck would I go along with a voluntary write-down of Greek debt??

From my perspective, if I do go along with it, I lose a asston of money on my bonds and my CDSs don’t get triggered because the write-down is considered “voluntary”. If I don’t go along with it, and enough other hedge funds also don’t go along with it, I either get paid in full or the CDSs I already own get triggered and I get paid in full (unless the counterparty who wrote the CDS goes under, but there’s always that risk).

Bottomline: I don’t go along with it.

None of this political finagling will change my mind. No argument for the stability of the European Union will change my mind. In fact, I will feel like arguing, hey if you force an involuntary voluntary write-down, then you are essentially making the meaning of CDS protection null and void. This is tantamount to ignoring legal contracts. And I’d have a pretty good point.

How’s this: let this shit go down, and start introducing a system that works, with a CDS market that is either reasonably regulated or nonexistent.

In the meantime, if I’m a Greek citizen, I’m wondering if I’ll ever be living in a country that has a consistent stock of aspirin again.

Mortgage settlement talks

If you haven’t been following the drama of the possible mortgage settlement between the big banks that committed large-scale mortgage fraud and the state Attorney Generals, then get yourself over to Naked Capitalism right away. What could end up being the biggest boondoggle coming out of the credit crisis is unfolding before us.

The very brief background story is this. Banks made huge bets on the housing market through securitized products (mortgage backed securities which were then often repackaged or rerepackaged). The underlying loans were often given to people with very hopeful expectations about the future of the housing market, like that it would only go up. In the meantime, the banks did very bad jobs of keeping track of the paperwork. In addition to that, many of the loans were actually fraudulent and a very large number of them were ridiculous, with resetting interest rates that were clearly unaffordable.

Fast forward to post-credit crisis, when people were having trouble with their monthly bills. The banks made up a bunch of paperwork that they’d lost or had never been made in the first place (this is called “robo-signing”). The judges at foreclosures got increasingly skeptical of the shoddy paperwork and started balking (to be fair, not all of them).

Who’s on the hook for the mistakes the banks made? The home owners, obviously, and also the investors in the securitized products, but most critically the taxpayer, through Fannie and Freddie, who are insuring these ridiculous mortgages.

So what we’ve got now is an effort by the big banks to come to a “settlement” with the states to pay a small fee (small in the context of how much is at stake) to get out of all of this mess, including all future possible findings of fraud or misdeeds. The settlement terms have been so outrageously bank-friendly that a bunch of state Attorney Generals have been pushing back, with the help of prodding from the people.

Meanwhile, the Obama administration would love nothing more than to be able to claim they cleaned up the mess and made the banks pay. But that story seriously depends on people not really understanding the scale of the problem and the meaning of the fine print of the proposed settlement.

If you want to learn more recent details about this potential tragedy, this post from Naked Capitalism got me so entranced that I actually missed my subway stop on the way to work and had to walk uptown from Canal. From the post:

The story did not outline terms, but previous leaks have indicated that the bulk of the supposed settlement would come not in actual monies paid by the banks (the cash portion has been rumored at under $5 billion) but in credits given for mortgage modifications for principal modifications. There are numerous reasons why that stinks. The biggest is that servicers will be able to count modifying first mortgages that were securitized toward the total. Since one of the cardinal rules of finance is to use other people’s money rather than your own, this provision virtually guarantees that investor-owned mortgages will be the ones to be restructured. Why is this a bad idea? The banks are NOT required to write down the second mortgages that they have on their books. This reverses the contractual hierarchy that junior lienholders take losses before senior lenders. So this deal amounts to a transfer from pension funds and other fixed income investors to the banks, at the Administration’s instigation.

Another reason the modification provision is poorly structured is that the banks are given a dollar target to hit. That means they will focus on modifying the biggest mortgages. So help will go to a comparatively small number of grossly overhoused borrowers, no doubt reinforcing the “profligate borrower” meme.

But those criticisms assume two other things: that the program is actually implemented. The experience with past consent decrees in the mortgage space is that the servicers get a legal get out of jail free card, a release, and do not hold up their end of the deal. Similarly, we’ve seen bank executives swear in front of Congress in late 2010 that they had stopped robosigning, which turned out to be a brazen lie. So here, odds favor that servicers will pretty much do nothing except perhaps be given credit for mortgage modifications they would have made anyhow.

Interestingly, Romney has gone on record siding with the homeowners. The following is a Romney quote:

The banks are scared to death, of course, because they think they’re going to go out of business… They’re afraid that if they write all these loans off, they’re going to go broke. And so they’re feeling the same thing you’re feeling. They just want to pretend all of this is going to get paid someday so they don’t have to write it off and potentially go out of business themselves.”

This is cascading throughout our system and in some respects government is trying to just hold things in place, hoping things get better… My own view is you recognize the distress, you take the loss and let people reset. Let people start over again, let the banks start over again. Those that are prudent will be able to restart, those that aren’t will go out of business. This effort to try and exact the burden of their mistakes on homeowners and commercial property owners, I think, is a mistake.

“This effort” must refer to the mortgage settlement. I’m with Romney on this one.

In 50 years, when we look back at this period of time, we may be able to describe it like this:

The financial system got high on profits from unreasonably priced homes and mortgages, underestimating risk, and securitization fees. When the truth came out they paid a pittance to escape their mistakes, transferring the cost to homeowners and the taxpayer and leaving the housing market utterly inflated and confused. The entire charade lasted decades and was in the name of not acknowledging what everyone already knew, namely that the banks were effectively insolvent.

Occupy the World Economic Forum

Seasonally adjusted news

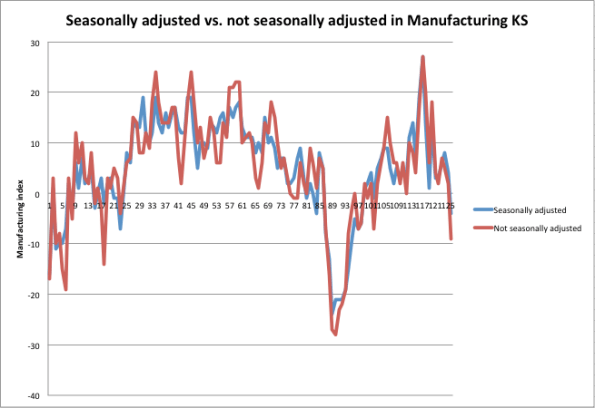

In one of my first posts ever, I talked about seasonal adjustment models and how they can work. I was sick of seeing that phrase go unexplained in the news all the time.

If I had been a bit more thoughtful, maybe I could have also mentioned various ways seasonal adjustment models could screw things up, or more precisely be screwed up by weird events. Luckily, a spokesperson from Goldman Sachs recently did that for me, and it was mentioned in this Bloomberg article. Those GS guys are smart, and would only mention this to Bloomberg if they thought everyone on the street knew it anyway, but I still appreciate them strewing their crumbs (it occurs to me that they might be trading on people’s overreactions to inflated good news right now).

Recall my frustration with seasonal adjustment models: they typically don’t tell you how many years of data they use, and how much they weight each year. But it’s safe to say that for statistics like unemployment and manufacturing, multiple years are used and more recent years are at least as important as older years. So events in the market that occurred in 2008 are still powerfully present in the seasonal adjustment model.

That means that, when the model is deciding what to expect, it looks at the past few years and kind of averages them. One of those years was 2008 when all hell broke loose, Lehman fell, TARP came into being, and Fannie, Freddie, and AIG were seized by the government. Lots of people lost their jobs and the housing and building industries went into freefall.

So the model thinks that’s a big deal, and compares what happened this year to that (and to the other years in the model, but that year dominates since it was such an extreme event), and decides we’re looking good. Here’s a picture from the Kansas Fed of the raw vs. seasonally adjusted manufacturing index results, from July 2001 to December 2011:

As one of my readers has already commented (darn, you guys are fast!), this just refers to manufacturing near Kansas, but the point I’m trying to make is still valid, namely that the seasonal adjustments clearly pale in comparison to the actual catastrophic event in 2008. However, that event still informs the seasonal adjustment model afterwards.

Because of the “golden rule” I mentioned in my post, namely that seasonal adjustment needs to on average (or at least in expectation) not add bias to the actual numbers, if things look better than they should in the second half of the year, that means they will look worse than they should in the first half of the year.

So be prepared for some crappy statistics coming out soon!

I still wish they’d just show us the graphs for the past 10 years and let us decide whether it’s good news.

How’s it going with the Volcker Rule?

Glad you asked.

Recall that Occupy the SEC is currently drafting a letter of public comment of the Volcker Rule for the SEC (for background on the Volcker Rule itself, see my previous post). I was invited to join them on a call with the SEC last week and I will talk further about that below, but first I want to give you more recent news.

Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism wrote this post a couple of days ago talking about a House Financial Services Committee meeting, which happened Wednesday. Specifically, the House Financial Services Committee was considering a study done by Oliver Wyman which warned of reduced liquidity if the Volcker Rule goes into effect. Just to be clear, Oliver Wyman was paid by a collection of financial institutions (SIFMA) who would suffer under the Volcker Rule to study whether the Volcker Rule is a good idea. In her post, Yves was discussed the meeting as well as Occupy the SEC’s letter to that Committee which refuted the findings of Oliver Wyman’s study.

Simon Johnson, who was somehow on the panel even though it was more or less stuffed with people who wouldn’t argue, had some things to say about how much it makes sense to listen to people who are paid to write studies in his New York Times column published yesterday. He also made lots of good arguments against the content of the study, namely about the assumptions going into it and how reasonable they are. From Simon’s article:

Specifically, the study assumes that every dollar disallowed in pure proprietary trading by banks will necessarily disappear from the market. But if money can still be made (without subsidies), the same trading should continue in another form. For example, the bank could spin off the trading activity and associated capital at a fair market price.

Alternatively, the relevant trader – with valuable skills and experience – could raise outside capital and continue doing an equivalent version of his or her job. These traders would, of course, bear more of their own downside risks.

If it turns out that the previous form or extent of trading existed only because of the implicit government subsidies, then we should not mourn its end.

The Oliver Wyman study further assumes that the sensitivity of bond spreads to liquidity will be as it was in the depth of the financial crisis, 2007-9. This is ironic, given that the financial crisis severely disrupted liquidity and credit availability more generally – in fact this is a major implication of the Dick-Nelson, Feldhutter and Lando paper.

If Oliver Wyman had used instead the pre-crisis period estimates from the authors, covering the period 2004-7, even giving their own methods the implied effects would be one-fifth to one-twentieth of the size (this adjustment is based on my discussions with Professor Feldhutter).

CSPAN taped the meeting, which was pretty long, but I’d suggest you watch minutes 50 through 57, where Congressman Keith Ellison took some of the panel to task for being, or acting, super dumb.

For whatever reason, Occupy the SEC wasn’t invited to the panel. You can read their letter that argues against Wyman’s study, which is on Yves’s post, or you can read this comment that one of the members of Occupy the SEC posted on Johnson’s NYTimes piece (“OW” refers to Oliver Wyman, the author of the paid study):

Your testimony at the hearings yesterday was a refreshing counterpoint to the other members of the panel.

On top of the flaws in the OW analysis you covered in the article, there was another misleading point that the OW report purported to prove.

The study focused on liquidity for corporate bonds, which SIFMA/OW characterized as ‘financing american businesses’ . But a quick review of the outstanding corporate bonds in the study reveals that the lions share of corporate bonds are CMOs and ABS. Additionally, the study reports that the majority of the holdings of corporate bonds are in the hands of the finance industry.

As a result the loss of liquidity anticipated by the SIFMA folks will mostly impact them, not the pensioners and soldiers (and their Congressmen) the bankers were trying to scare with the OW loss estimates.

If the banks are forced to withdraw as market makers for this debt, replacement market makers won’t enter until these bonds trade at much lower levels. These losses are currently stranded (and disguised) in the banking system, and by extension are inflating the value of the funds invested in these bonds.

It’s critical that the market making rules are clarified to ensure that liquidity provision for these instruments is driven out of the protected banks and into a transparent market where the mispricing will be corrected and the losses will be properly recognized.

So just to summarize, the Congressional committee listened to the results of a paid study talking about how bad the Volcker Rule would be for the market, when in fact it would be good for the market to be uninsured and realistic.

I’m not a huge fan of the Volcker Rule as it is written, but these are really terrible reasons to argue against it. To my mind, the real problem is that, as written, the Volcker Rule is too easy to game and has too many exceptions written into it.

Going back to the call with the SEC (and with Occupy the SEC). I haven’t kept abreast of the details of the Volcker Rule like these guys (they are super relentless), but I did have some questions about the risk part. Namely, were they going to end up referring to an already existing risk regulatory scheme like Basel or Basel II, or were they creating something separate altogether? They were creating something separate. They mentioned that they weren’t interested in risk per se but only to the extent that wildly fluctuating risk numbers expose proprietary trading, which is the big no-no under the Volcker Rule.

But here’s the thing, I explained, the risk numbers you are asking for are so vague that it’s super easy, if I’m a bank, to game this to make my risk numbers look calm. You don’t specify the lookback period, you don’t specify the kind of Value-at-Risk, and you don’t compare my risk model worked out on a benchmark portfolio so you really don’t know what it’s saying. Their response was: oh, yeah, um, if you could give us better wording for that section that would be great.

So to re-summarize, we have “experts”, being paid by the banks, who explain to Congress why we shouldn’t let the Volcker Rule go through, and in the meantime we’ve assigned the SEC the job of writing that rule even though they don’t know how to game a risk model (there’s a good example here of JP Morgan doing just that last week).

One last issue: when we asked about why repos had been exempted sometime in between the writing of the statute and the design of the implementation, the SEC people just told us we’d “have to ask the Fed that”.

Quantitative analysis of regulatory capture

I wrote earlier about how the movie “Inside Job” brought to light the issue of conflict of interest for business school professors, and I discussed Columbia and Harvard Business Schools. As some people pointed out, I forgot to mention economists.

Luckily the editors at Bloomberg took up that cause for me. Yesterday they published an opinion piece saying that disclosure won’t even be sufficient (but that it is absolutely necessary). From the article:

Disclosure, though, won’t eliminate the actual conflicts. Even the best-intentioned economists — and particularly those in the area of finance — face a litany of influences pushing them toward a rosier view of the industries they study. In a yet-to-be-published paper, Luigi Zingales, a finance professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, likens the pressure to regulatory capture. A pro-business attitude, he notes, can increase an economist’s chances of landing lucrative consulting, expert-witness and research contracts, and can facilitate publication in academic journals whose editors are themselves captured. (Zingales is a contributor to Bloomberg View’s Business Class blog and has accepted money for speeches to Dimensional Fund Advisors, a hedge fund, and Banca Intermobiliare, an Italian private bank, among others.)

As a small test, Zingales looked at the 150 most-downloaded papers that had been done on executive pay — a subject he reasoned could legitimately be argued either way. He found that papers supporting high pay for top executives were 55 percent more likely to be published in prestigious economic journals, suggesting that the editors, also academic economists, have a bias.

I think this is an important study, and I look forward to reading it. Beyond the question of economists and disclosure, it points to a new subfield of quantitative analysis: the quantitative analysis of regulatory capture. I hope it is being done well: in other words, it could be true that high pay for top executives is really a better idea, and that’s why those studies are being published in prestigious economic journals. There has to be some way to separate the techniques from the politics of the results. It’s certainly an interesting question.

If we quants do this right, and especially if we make our models open source, then we potentially have the ability to measure the extent to which, when politicians and judges and the public get “expert” opinions, the information they receive is coming directly from the financial lobbyists (or other kinds of lobbyists) who are paid to think a certain way. It’s a possible first step towards removing some of the influence of money from decisions such as how much regulation or capital requirements we should impose on banks, for example.

Sunday Links

What do an upscale nightclub for Wall Streeters and the People’s Library from #Occupy Wall Street have in common? Turns out, nothing.

Someone thinks we can cure accounting shenanigans by rotating accounting firms. I’m not convinced.

I like this story from Matt Taibbi about one of the biggest assholes in the world.

For whatever reason I can’t get enough of this picture from a recent car show:

High Frequency Trading and Transaction Taxes

If you look at this list of the 20 biggest donors of the 2012 election, and you scroll down to number 20, you’ll find out stuff about Robert Mercer:

Robert Mercer is co-CEO of the $15 billion hedge fund company Renaissance Technologies. In 2009, according to the New York Daily News, he accused a builder of overcharging him $2 million for a construction project in his mansion—a “museum-quality” model train display “about half the size of a basketball court.” During the 2010 midterms, Mercer was outed as the funder behind $300,000 worth of attack ads targeting Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.). In the 2012 election cycle, he and his wife Diana have given $150,000 to the Republican National Lawyers Association and $100,000 to the free-market super-PAC Club for Growth Action.

Total giving for 2012 race: $384,100

• Giving to outside-spending groups: $260,000

• Giving to candidates and parties: $124,100

First, if I’m the model train set guy from above, I overcharge Mercer $2M and hope that he’s too embarrassed to sue me. And I am wrong.

Second, let’s look a bit more into the attack ads against DeFazio. Why is he spending so much time to work against this guy? Oh maybe this explains it. DeFazio was trying to impose a small transaction tax to curb high frequency trading, and Renaissance Technology, where Mercer works, makes their money through high frequency trading on the futures exchanges:

Capitol Hill Democrats introduced legislation today that would impose a tax on financial transactions in order to curb high-frequency trading and force Wall Street to contribute a bigger share to the federal budget.

A measure written by Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, and Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., would place a 0.03% levy on financial trading in stocks and bonds at their market value. It also would cover derivative contracts, options, puts, forward contracts and swaps at their purchase price.

So this is how politics works. As Sarkozy mentioned in this Bloomberg article where he was discussing imposing a similar transaction tax in France:

“If France waits for others to tax finance, then finance will never be taxed,” Sarkozy said today in a speech in the eastern French city of Mulhouse.

It seems like the Harkin/DeFazio transaction tax bill is still alive, for now. What’s so worrisome about it? To find out I registered to read this article from Investment News (registration is free), which starts out quite nicely:

Hark: Beware of Harkin tax plan

Investors, beware of the financial transactions tax proposed by Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, and Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore. The tax may appear to have no chance of adoption at present, with the Republicans in control of the House and in position to block many proposals in the Senate, but the situation could change after the 2012 elections.

If Barack Obama retains the presidency and the Democrats regain control of both houses of Congress, we could see a tax on securities trades, especially if the passions evidenced by the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations remain high.

Woohoo! I love it when people are afraid of Occupy Wall Street, especially when they think they are only talking to their insider friends. After explaining the scope of the tax (again, 3 cents on 100 dollars), the article goes on:

In a breathtaking display of economic ignorance, Mr. Harkin declared: “This measure is not likely to impact the decision to engage in productive economic activity. There’s no question that Wall Street can easily bear this modest tax.”

Does Mr. Harkin not realize that customers, not Wall Street, would pay the tax? As opponents of the proposal argue, the proposed levy — effectively, a sales tax — would increase the cost of investing and be passed on to the ultimate customer, not absorbed by the brokerage firms, hedge funds and other professional traders at whom it is nominally aimed.

In effect, it also is a tax on liquidity. As anyone who has studied economics knows, when you tax something, you get less of it, so the result would be less liquid markets and more-costly transactions.

The article then goes on to warn that such a tax would move business offshore:

Finally, a transactions tax might drive trading and investing offshore to financial centers, such as Singapore or Dubai, that don’t impose such taxes. Academic research suggests that after the imposition of a transactions tax, market volatility would rise, while trading volume —and with it, liquidity — declined.

Just in case you’re not sufficiently worried yet, the article makes some further scary suggestions, which bizarrely allows for the fact that the current plan is benign:

Other dangers regarding the transactions tax proposal are that the low initial tax rate, 0.03%, might be absorbed by investors without too much pain, leading it to be raised quickly to a more burdensome and damaging rate.

That is what happened with the income tax in the U.S., and, more recently, with the value-added tax throughout Europe.

Another danger is that a transactions tax could be extended quickly to other financial transactions, including credit and debit card transactions, checks and bill payments. These likely would be even more damaging to economic activity.

The financial services industry should continue to resist the financial transactions tax, even at the proposed low rate. Once the camel’s nose is in the tent, the whole camel soon follows.

I asked a quant friend of mine what he thought of this article, and he said the following:

I’m personally not a huge fan of transaction taxes because I guess I feel trades should be encouraged (people should, for example, be able to have an S&P500 account instead of a checking account, where you sell units of S&P each time you buy some milk) and in general tight spreads means more actionable information (in the sense of knowing whether a bank is solvent for example, or allocating resources to build a new power plant). In addition, they are often avoided at some additional cost to investors. In the UK, they have a stamp tax on equities, and as a result only a few people trade equities, and almost all funds trade “swaps” with some additional arb/copmlexity added to the system as a result.

That said, the doomsaying in the article is definitely overboard. It would certainly wipe out a lot of HF trading, which is of limited value to society (I think HF does make for better pricing, but the resources put into it might not match the societal benefit of the slightly more accurate prices).

This would cause some trading to go offshore. In the UK for example, various regulations were (a small) part of the reason ManU decided to list in Singapore. The loss in capital gain taxes are from a bunch of sources, but one of the major ones is sure to be deferred sales, meaning the taxes would just be paid later.

It does make some sort of intuitive sense to match the costs associated with overseeing transactions paid for by the transactions though. If you feel that financial transactions are burdensome and need more regulation, the people who are causing that burden should pay. Whether that should be via a transaction tax or by a profit tax or by an exchange/regulatory fee, I don’t know.

(You know my bias, that it’s really the hidden transactions that are the main issue, and so I think if anything you should be taking financial intermediaries for having illiquid/non-tradable assets on their books rather than encouraging them to have more of it).

I’m left kind of rooting for the transaction tax, personally, and it’s not just because I want to see Mercer miserable; it can be seen as a tax that most people will not notice but people who make enormous number of bets will be affected by. On the one hand, this means it’s a truly progressive tax, and on the other hand, it means you will actually need to think a trade is worthwhile before making it.

Shareholder value and Adam Smith

I’m reading a fascinating “Ethnography of Wall Street” called Liquidated. This was written by anthropologist Karen Ho, who did her graduate student field work at an investment bank in the mid-1990’s.

As a woman and as a minority, Ho had an interesting, outsider’s view into the culture of investment banking, and the first third of the book describes that culture in painful detail; I might write a further post on her observations, but suffice it to say I recognize her experiences as both shocking (because awful) and totally unsurprising (because familiar).

What I’ve really gotten into in the middle third of the book (not done yet! I’m reading it on my kindle app on the phone on the subway to and from work) is her explanation of the history of the cult of shareholder value. Although she starts in the present and goes backwards, I’ll summarize (and simplify) her narrative by starting earlier and going forward.

Back when Adam Smith wrote his book, most commerce was conducted by small business owners. Smith wrote that the small business owner, by having complete control and by profiting directly from his business, will improve the overall system by acting in his self interest. This is the fundamental belief behind the “invisible hand” theory.

Fast forward to the beginning of the 20th century. The stock market was created, and sold to people, as a way of having ownership of companies without having responsibility, or importantly, control. In other words the fundamental idea of owning a stock was to separate the Adam Smith “ownership/control” concept. Incidentally, Ho has quite a few excellent quotations from Adam Smith explaining that if you do this, your enterprise is destined for failure.

Now move forward to post-World War II. At this point we see the rise of the large corporation, and stock holders continue to own but not control, and managers of the corporations consider the corporations to be social entities, and consider their obligations diffused among stake holders such as employees, customers,stockholders, and the general public.

At some point it seems that investment bankers, who wanted a bigger piece of this pie, and economists got together and cooked up the shareholder value theory. According to Ho, modern economics at this point in history was still relying on the Adam Smith concept of individuals working in their self-interest. It had no theory of corporations, and didn’t know what to make of them.

Except it did know how to squeeze them into the tiny box they’d already built. In order to do this, though, they had to recombine the concept of ownership and control, and reimagine the corporation as an entity, where the role of the small business owner would be taken by the collection of shareholders.

Essentially, then, the idea was to convince the managers and the market itself that the only stakeholder to really pay attention to is the supposedly unified group of shareholders. The corporation should do everything in its power to increase share price, for the sake of this shareholder which was essentially mute (because they didn’t have power) but for whom the investment banker was more than happy to speak (for a large fee involved in restructuring the corporation). It also resulted in the CEO-as-shareholder concept of stock options etc. so that the CEO would be more aligned with his “natural” duties.

One reason this is a screwy concept: shareholders don’t actually have control, nor do they really want control (or responsibility). Most shareholders want to think of their stocks as fluid, like money, except riskier. Indeed Ho makes the argument, which I buy, that shareholders traded control and responsibility for liquidity, which is more meaningful to them.

Another reason this is a screwy concept: in effect, the only people who actually gain from the “shareholder value” revolution in the 1980’s and 1990’s were the investment bankers themselves, and some of the managers of those corporations. Ho goes into detail on how she reached this conclusion, and her facts are convincing, but I was already convinced by observing the lack of faith in the markets right now by regular shareholders (most people through their 401K’s) and by the monstrous size of the financial system.

I really like the way Ho explains this stuff. In particular I enjoy the way she pokes holes in invented nostalgic histories; she talks about how people generate authenticity for their “shareholder value” theory by inventing a past that never was, when shareholders had more say in the running of the company. In fact she does that more than once, and you start to realize how much you can get away with by relying on people not knowing even recent history.

I am looking forward to the last third of the book!

Open Models (part 1)

A few days ago I posted about how riled up I was to see the Heritage Foundation publish a study about teacher pay which was obviously politically motivated. In the comment section a skeptical reader challenged me on a few things. He had some great points, and I’d love to address them all, but today I will only address the most important one, namely:

…the criticism about this particular study could be leveled to any study funded by any think tank, from the lowly ones, to the more prestigious ones, which have near-academic status (e.g. Brookings or Hoover). But indeed, most social scientists have a political bias. Piketty advised Segolene Goyal. Does it invalidate his study on inequality in America? Rogoff is a republican. Should one dismiss his work on debit crises? I think the best reaction is not to dismiss any study, or any author for that sake, on the basis of their political opinion, even if we dislike their pre-made tweets (which may have been prepared by editors that have nothing to do with the authors, by the way). Instead, the paper should be judged on its own merit. Even if we know we’ll disagree, a good paper can sharpen and challenge our prior convictions.

Agreed! Let’s judge papers on their own merits. However, how can we do that well? Especially when the data is secret and/or the model itself is only vaguely described, it’s impossible. I claim we need to demand more information in such cases, especially when the results of the study are taken seriously and policy decisions are potentially made based on them.

What should we do?

Addressing this problem of verifying modelling results is my goal with defining open source models. I’m not really inventing something new, but rather crystallizing and standardizing something that is already in the air (see below) among modelers who are sufficiently skeptical of the underlying incentives that modelers and their institutions have to look confident.

The basic idea is that we cannot and should not trust models that are opaque. We should all realize how sensitive models are to design decisions and tuning parameters. In the best case, this means we, the public, should have access to the model itself, manifested as a kind of app that we can play with.

Specifically, this means we can play around with the parameters and see how the model changes. We can input new data and see what the model spits out. We can retrain the model altogether with a slightly different assumption, or with new data, or with a different cross validation set.

The technology to allow us to do this all exists – even the various ways we can anonymize sensitive data so that it can still be semi-public. I will go further into how we can put this together in later posts. For now let me give you some indication of how badly this is needed.

Already in the Air

I was heartened yesterday to read this article from Bloomberg written by Victoria Stodden and Samuel Arbesman. In it they complain about how much of science depends on modeling and data, and how difficult it is to confirm studies when the data (and modeling) is being kept secret. They call on federal agencies to insist on data sharing:

Many people assume that scientists the world over freely exchange not only the results of their experiments but also the detailed data, statistical tools and computer instructions they employed to arrive at those results. This is the kind of information that other scientists need in order to replicate the studies. The truth is, open exchange of such information is not common, making verification of published findings all but impossible and creating a credibility crisis in computational science.

Federal agencies that fund scientific research are in a position to help fix this problem. They should require that all scientists whose studies they finance share the files that generated their published findings, the raw data and the computer instructions that carried out their analysis.

The ability to reproduce experiments is important not only for the advancement of pure science but also to address many science-based issues in the public sphere, from climate change to biotechnology.

How bad is it now?

You may think I’m exaggerating the problem. Here’s an article that you should read, in which the case is made that most published research is false. Now, open source modeling won’t fix all of that problem, since a large part of is it the underlying bias that you only publish something that looks important (you never publish results explaining all the things you tried but didn’t look statistically significant).

But think about it, that’s most published research. I’d like to posit that it’s the unpublished research that we should be really worried about. Note that banks and hedge funds don’t ever publish their research, obviously, because of proprietary reasons, but that this doesn’t improve the verifiability problems.

Indeed my experience is that very few people in the bank or hedge fund actually vet the underlying models, partly because they don’t want information to leak and partly because those models are really hard. You may argue that the models are carefully vetted, since big money is often at stake. But I’d reply that actually, you’d be surprised.

How about on the internet? Again, not published, and we don’t have reason to believe that they are more correct than published scientific models. And those models are being used day in and day out and are drawing conclusions about you (what is your credit score, whether you deserve a certain loan) every time you click.

We need a better way to verify models. I will attempt to outline specific ideas of how this should work in further posts.

Who the hell is buying European debt?

I’m a bit confused about the “successful” European sovereign debt auctions we’ve been hearing about lately.

If I’m a European bank, say in Italy, Spain, or Portugal, or maybe even France, then about 10 months ago or so I’d be buying all the sovereign debt of my own country that I can get or that my country wants me to, because I’d figure, hey we’re in the same boat- if my country defaults then we’re going down, probably exorcised from the Euro zone.

But nowadays, because of Greece’s example, it seems increasingly likely that a country could default on its bonds, and if orderly (and “voluntary”), the country gets to stay in the Euro zone and the banks get to live on- if they can.

So if I’m a European bank now in a peripheral country, I’m going to try to stay solvent in the case of my country’s default. And I don’t even need to be completely solvent, I just need to be more solvent than most of the other banks in my country, because, especially if the Euro zone does stay intact, they probably won’t allow all the banks to fail, but they might easily let the weakest banks fail.

Wouldn’t that reasoning mean I’d avoid buying my country’s crappy debt? So why is crappy debt bought at all anymore? I realize that the yields are high, but I don’t think they’re high enough, and I just don’t get it. Maybe I’m being dumb. Here are the possibilities as I see them:

- I’m exaggerating the problem altogether, and the debt is actually fairly priced and not so risky. In answer to this let me quote Princeton economist Alan Blinder, a former U.S. Federal Reserve vice chairman, in this Wall Street Journal article about what to worry about in 2012: “Europe is absolutely my No. 1 concern. It is so far in the lead I can’t think of what my No. 2 concern is.”

- The governments are putting backroom pressure on the banks to buy their debt. This seems quite probable. I definitely get the impression that there’s real politics behind the accumulation of Greek debt in French banks, for example, because otherwise the enormous holdings in BNP Paribas and others is frankly impenetrable, and certainly not in the interest of the bank itself.

- There is some short or medium term gaming of the system going on right now, using the ECB’s recent action to restore “liquidity” in order to look better. Specifically, we have this quote from Bill Gross of PIMCO: “Amazingly, Italian banks are now issuing state guaranteed paper to obtain funds from the European Central Bank (ECB) and then reinvesting the proceeds into Italian bonds, which is QE by any definition and near Ponzi by another.”

- Actually, the next time peripheral countries issue debt nobody will show up to buy it.

I’d love to hear comments from people who have different theories.

It takes imagination to be boring

I suffer from a lack of imagination.

I have been so inculcated in the necessary complexity of finance and banking, that I’ve lost touch with some basic, simple realities. I have been brainwashed by the half-assed and lame attempts at regulation by the elements of the Dodd-Frank bill, losing myself in the details of the Volcker Rule for example, and I’ve lost the forest for the trees. I’m spending my time furiously figuring out how to allow banks to have all of their goodies (CDS, derivatives, repos, etc.), but not let them eat so much they get themselves (and us) sick.

Sometimes you need imagination to be boring.

Luckily, there was an op-ed article in the New York Times yesterday which served as a wake-up call. The article is called “Bring Back Boring Banks” and it’s written by Amar Bhide. I kind of feel like quoting the entire article, since it’s all so good, but I’ll make do with this part (emphasis mine):

Guaranteeing all bank accounts would pave the way for reinstating interest-rate caps, ending the competition for fickle yield-chasers that helps set off credit booms and busts. (Banks vie with one another to attract wholesale depositors by paying higher rates, and are then impelled to take greater risks to be able to pay the higher rates.) Stringent limits on the activities of banks would be even more crucial. If people thought that losses were likely to be unbearable, guarantees would be useless.

Banks must therefore be restricted to those activities, like making traditional loans and simple hedging operations, that a regulator of average education and intelligence can monitor. If the average examiner can’t understand it, it shouldn’t be allowed. Giant banks that are mega-receptacles for hot deposits would have to cease opaque activities that regulators cannot realistically examine and that top executives cannot control. Tighter regulation would drastically reduce the assets in money-market mutual funds and even put many out of business. Other, more mysterious denizens of the shadow banking world, from tender option bonds to asset-backed commercial paper, would also shrivel.

This is what we need to do. Thank you Amar Bhide, for having the clarity to say it.

Matt Stoller explains politics

I’ve never understood politics, partly because they’re complicated, partly because the people who do understand politics are so heavily involved they don’t know how to contextualize for people like me. I’ve come to think of it as a lot like finance, where there’s power to be had by withholding information, and part of that power is wielded simply by inventing a new vocabulary that makes people on the outside feel tired and hopeless. You really need a tour guide, a translator, to walk you through stuff to achieve a decent level of understanding.

I now consider Matt Stoller my personal translator. Matt regularly contributes to Naked Capitalism, my go-to blog for informed, vitriolic insights into the corrupt world of finance. His recent post on Naked Capitalism concerning Ron Paul and liberals beautifully explains how confused modern liberals are when confronted by someone like Ron Paul, who is both unattractive and on their side for a number of reasons. I confess that I’ve been that confused liberal myself at many an #OWS Alternative Banking Working Group meeting, when the Ron Paul fans come and talk about Fed transparency.

But Matt doesn’t just tell a good story, although he does that. He also give you insight into the process of politics. He peppers his story with helpful, nerdy explanations like this:

An old Congressional hand once told me, and then drilled into my head, that every Congressional office is motivated by three overlapping forces – policy, politics, and procedure. And this is true as far as it goes. An obscure redistricting of two Democrats into one district that will take place in three years could be the motivating horse-trade in a decision about whether an important amendment makes it to the floor, or a possible opening of a highly coveted committee slot on Appropriations due to a retirement might cause a policy breach among leadership. Depending on committee rules, a Sub-Committee chairman might have to get permission from a ranking member or Committee Chairman to issue a subpoena, sometimes he might not, and sometimes he doesn’t even have to tell his political opposition about it. Congress is endlessly complex, because complexity can be a useful tool in wielding power without scrutiny. And every office has a different informal matrix, so you have to approach each of them differently.

Another recent Stoller post that really blew my mind was How the Federal Reserve Fights, which explained Matt’s experiences as a Senior Policy Advisor to Alan Grayson, a congressman on the Financial Services Committee in 2009-2011. Grayson teamed up with Ron Paul to force more transparency at the Fed. It’s an awesome story, but my favorite part, because I’m such a nerd and I love my nerd heroes, is the following:

When it gets down to crunch time, as a staffer going up against a big force of lots of lawyers, you get really tired and cut corners. One obstacle in legislating is that it is really hard to tell what bills do, because they have multiple provisions like “In Section 203, delete “do” and replace with “shall”. You have to constantly reference pieces of the code and compare changes, which gets confusing. It’s like doing “track changes”, but on paper and with multiple versions. This is a problem software could easily solve and I’ve heard that agencies and (probably the Fed) have such software. But I didn’t. So the Fed thought we would do nothing more than cursory reading of Watt’s amendment, and rely on their validators who told us the amendment would increase transparency. And this is where Grayson showed legislative genius. We were exhausted, but he got all the difference pieces of the law, and spent a few hours deciphering exactly what this amendment meant. And he figured out that not only did the amendment not open up the Fed facilities to independent inspection, it actually increased the secrecy of the Fed. If you want the gory details, here’s Grayson’s argument during the markup.

I’m kind of wishing Matt Stoller would write a book about “How Politics Works,” but then again does anybody read books anymore? Is it better for him to just continue to write timely blog posts? I’ll take what I can get.

Information loss

When people ask me why the financial system is so complicated, I always say the same thing: because it benefits the insiders of the financial system to make it that way. The more complicated and opaque something is, the more opportunities to extract fees and withhold information. Or rather, to withhold information in order to extract fees.

In some sense you can think of the financial system as a huge “information loss” system, where people get paid based on how much more information they know than you do. Incidentally, this theory flies in the face of most economic assumptions of transparency, and explains the origin of the phrase “dumb money.” And it’s not my idea, it’s kind of an elemental fact for insiders; I’m bringing it up because I want to make sure people are aware of it.

As an analogy, think of the situation when you buy a used car from someone. They tell you some things, like its make and model, and they may let you test drive it, but you end up not knowing how many accidents it’s been in, and stuff like that. Your partial information in general lets them make money.

It’s kind of understandable why there’s so much insider trading going on. Insider trading is the ultimate and most efficient way to profit from information.

Another good example of information loss is with mortgages, and mortgage-backed securities. The original idea behind securitizing mortgages was that investors get to buy pieces of pools of mortgages, which “behave better” than individual mortgages: whereas an individual can refinance (and often does, when interest rates go down) or default, it’s less likely that a majority of the people in a pool refinance or default.

[Let’s ignore for now the issue that the banks got so high on the profits of securitization that the assumption of better behavior of pools got thrown out the window as the underlying mortgages became worse and worse – a gleaming example of information loss.]

In selling these pools, the banks were charging fees so that you, the investor, wouldn’t have to “deal with the details” of all of the individual mortgages in the pool. This is one way that people withhold information and charge a fee for it, by calling it a chore.

And it is a chore, if you actually do it. However, in the case of mortgages, lots of banks charged that fee for that chore and then never actually did the chore– they kept terrible accounts of the mortgages, and when they started to default in large numbers, started illegally pretending their papers were in order, through “robo-signing,” in order to foreclose quickly.

Here’s something you can do if you have a mortgage. Demand to see your mortgage note. It turns out there’s a legal way for you to ask your bank to trace the ownership of your mortgage through the securitization system, and you can do it for fun, you don’t need to be late on your mortgage payments or anything.

There does seem to be a risk associated with asking to see your note, however, namely to your credit score, which is bullshit. There’s also a form letter of complaint if your bank somehow doesn’t come up with the answer.

Economist versus quant

There’s an uneasy relationship between economists and quants. Part of this stems from the fact that each discounts what the other is really good at.

Namely, quants are good at modeling, whereas economists generally are not (I’m sure there are exceptions to this rule, so my apologies to those economists who are excellent modelers); they either oversimplify to the point of uselessness, or they add terms to their models until everything works but by then the models could predict anything. Their worst data scientist flaw, however, is the confidence they have, and that they project, in their overfit models. Please see this post for examples of that overconfidence.

On the other hand, economists are good at big-picture thinking, and are really really good at politics and influence, whereas most quants are incapable of those things, partly because quants are hyper aware of what they don’t know (which makes them good modelers), and partly because they are huge nerds (apologies to those quants who have perspective and can schmooze).

Economists run the Fed, they suggest policy to politicians, and generally speaking nobody else has a plan so they get heard. The sideline show of the two different schools of mainstream economics constantly at war with each other doesn’t lend credence to their profession (in fact I consider it a false dichotomy altogether) but again, who else has the balls and the influence to make a political suggestion? Not quants. They basically wait for the system to be set up and then figure out how to profit.

I’m not suggesting that they team up so that economists can teach quants how to influence people more. That would be really scary. However, it would be nice to team up so that the underlying economic model is either reasonably adjusted to the data, or discarded, and where the confidence of the model’s predictions is better known.

To that end, Cosma Shalizi is already hard at work.

Generally speaking, economic models are ripe for an overhaul. Let’s get open source modeling set up, there’s no time to lose. For example, in the name of opening up the Fed, I’d love to see their unemployment prediction model be released to the public, along with the data used to train it, and along with a metric of success that we can use to compare it to other unemployment models.

Crappy modeling

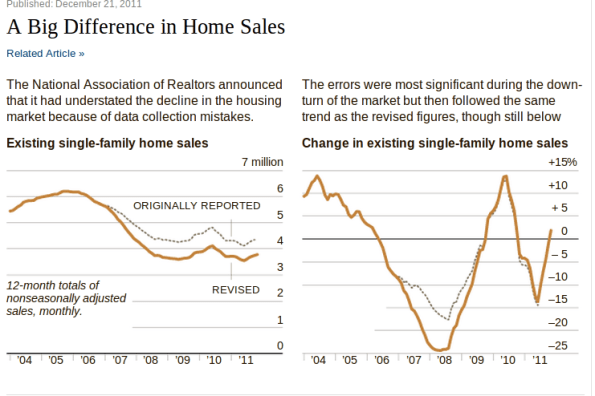

I’m here to vent today about crappy modeling I’m seeing in the world of finance. First up is the 14% corrections of home sales from 2007 to 2010 we’ve been seeing from the National Association of Realtors. From the New York Times article we see the following graph:

Supposedly the reason their models went so wrong was that they assumed a bunch of people were selling their houses without real estate agents. But isn’t this something they can check? I’m afraid it doesn’t pass the smell test, especially because it went on for so long and because it worked in their favor, in that the market didn’t seem as bad as it actually was. In other words, they had a reason not to update their model.

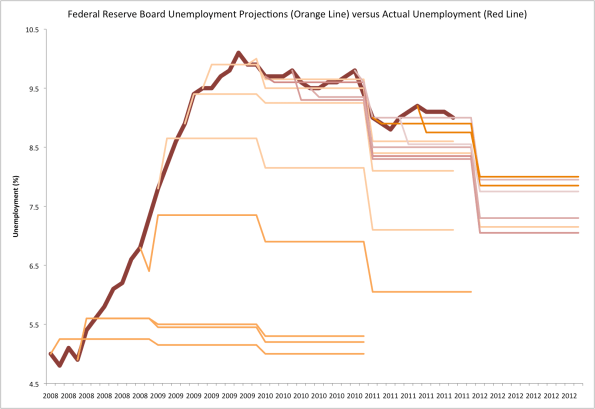

Here’s the next on our list, namely unemployment projections from the Fed versus actual unemployment figures, brought to us by Rortybomb:

Again we see outrageously bad modeling, which is always and consistently biased towards good news. Is this better than having no model at all? What kind of model is this biased? At the very least can you shorten your projection lengths to make up for how inaccurate they are, kind of like how weather forecasters don’t predict out past a week?

Finally, I’d like to throw in one last modeling complaint, namely about weekly unemployment filings. It seems to me that every December for the past few years, the projected unemployment filings have been “surprising” economists with how low they are, after seasonal adjustment.

First, seasonal adjustment is a weird thing, and was the subject of one of my earliest posts. We effectively don’t really know what the numbers mean after they are seasonally adjusted. But even so, we can imagine a bit: they look at past years and see how much the filings typically dip or surge (sadly it looks like they typically surge) at the end of the year, and assume the same kind of dip or surge should happen this year.

Here’s my thing. The fact that the filings surge less than expected the fourth or fifth year of an economic slump shouldn’t surprise anyone. These are real people, losing their real jobs with real consequences, right before Christmas. If you were a boss, wouldn’t you have made sure to have already fired someone in the early Fall or be willing to wait til after the holidays, especially when they know the chances of getting hired again quickly are very slim? Bosses are people too. I do not have statistically significant evidence for this by the way, just a theory.

Need your vote

Footnoted needs your vote on the most outrageous handout to executives in 2011. Here are the candidates:

- MF Global agreeing to pay then-CEO Jon Corzine a $1.5 million retention bonus months before the company imploded.

- Clear Channel Media Holdings paying $3 million a year to a company controlled by Bob Pittman so that Pittman can fly in a Mystere Falcon 900 that Pittman owns for both business and personal use.

- Leo Apotheker collecting around $25 million in severance and other benefits from Hewlett-Packard, including relocation back to France or Belgium after less than a year on the job.

- IBM’s outgoing CEO Samuel Palmisano becoming eligible for as much as $170 million in retirement benefits, just by waiting until he was past 60 to announce his retirement.

- Nabors Industries agreeing to pay outgoing CEO Eugene Isenberg $100 million in severance on his way out the door.

Vote here.

Also, please read a letter to Jamie Dimon that I enjoyed, from the Reformed Broker blog. From the letter:

So please, do us all a favor and come to the realization that the loathing you feel from your fellow Americans has nothing to do with your “success” or your “wealth” and it has everything to do with the fact that your wealth and success have come at a cost to the rest of us. No one wants your money or opportunities, what they want is the same chance that their parents had to attain these things for themselves. You are viewed, and rightfully so, as part of the machine that has removed this chance for many – and that is what they hate.

Why work?

In his recent Vanity Fair article, Joseph Stiglitz puts forth the following theory about why the Great Depression was inevitable (and in particular wouldn’t have been prevented by the Fed loosening monetary policy). Namely, that our society was transitioning from an agrarian society to something else- which turned out to be a manufacturing society, kicked off in earnest at the beginning of World War II. He goes on to say that we are now going through another great transition, from manufacturing to something else- he calls it service. And he also says there’s no way monetary policy will fix this trauma either- we need to invest heavily in infrastructure in order to prepare ourselves for the coming service society we will be.

Take a few steps back, and we see this picture: a hundred years ago we got so efficient at farming that we didn’t need everyone to farm to be well fed. Then we figured out how to make things so efficiently that we don’t need to worry about having enough stuff. So now, what are we all working for exactly? If service means we take care of each other (medical stuff) and we educate each other, that is fine, but not everyone is a doctor or a teacher. If service means we spend all our time making video games and entertaining each other, than it seems like we need to rethink this plan.

There are two essays I’ve read about the nature of this change that I think will help us rethink work and how our society values work and how it doles it out. First, there’s this highbrow essay on the language of work. From the essay:

Work deploys a network of techniques and effects that make it seem inevitable and, where possible, pleasurable. Central among these effects is the diffusion of responsibility for the baseline need to work: everyone accepts, because everyone knows, that everyone must have a job. Bosses as much as subordinates are slaves to the larger servomechanisms of work. In effect, work is the largest self-regulation system the universe has so far manufactured, subjecting each of us to a panopticon under which we dare not do anything but work, or at least seem to be working, lest we fall prey to a disapproval all the more powerful for its obscurity. The work idea functions in the same manner as a visible surveillance camera, which need not even be hooked up to anything. No, let’s go further: there need not even be a camera. Like the prisoners in the perfected version of Bentham’s utilitarian jail, workers need no overseer because they watch themselves. When we submit to work, we are guard and guarded at once.

What is less clear is why we put up with this demand-structure of a workplace, why we don’t resist more robustly. As Max Weber noted in his analysis of leadership under capitalism, any ideology must, if it is to succeed, give people reasons to act. It must offer a narrative of identity to those caught within its ambit, otherwise they will not continue to perform, and renew, its reality. As with most truly successful ideologies, the work idea latches on to a very basic feature of human existence: our character as social animals forever competing for relative advantage.

The author Mark Kingwell makes a pretty convincing case that people have bought into work just as they buy into other cultural norms. It underlines the real audacity of the #Occupy Wall Streeters who dared to do something with their time than be baristas at Starbucks.

Paired with the Stiglitz view of our culture and its future, though, it makes me think about the extent to which we’ve synthesized work. Mark Kingwell points out that one of the major outputs of workplaces is more work, a kind of purely synthetic made-up idea which we all need to believe in as long as we are all convinced about this work-as-cultural imperative.

The quintessential example of work-creating-work comes from finance, of course, where there isn’t even really a product at the end of the day. It’s essentially all completely made up, pushing around numbers on a spreadsheet.

What happens when people question this industry and its associated maniacal belief in work as moral? I say “maniacal” based on the number of hours people put in at most financial firms, sacrificing their families and even their internal lives, not to mention their associated martyred attitudes at having worked so hard.

This article from Bloomberg addresses the issue indirectly. In it, Richard Sennett talks about what bonds people to their colleagues and their workplace. He compares manufacturing jobs in 1970’s Boston to the recent financial services industry, and notes that people nowadays in finance have no loyalty to each other or to their workplace, and also have very little respect for the bosses. He blames this on unthoughtful hierarchical structures and the fact that bosses are essentially incompetent and everybody knows it. He concludes his article as follows:

These employees were relentless judges of their bosses, always on the lookout for details of conversation or behavior to suggest that the executives didn’t deserve their powers and perks. Such vigilance naturally weakened the bosses’ earned authority. And it didn’t make the people judging feel good about themselves either, as they were stuck in the relationship. On the contrary, it was more likely to be embittering than a cause for secret satisfaction.

Even for those workers who have recovered quickly, the crash isn’t something they are likely to forget. The front office may want to get back as quickly as possible to the old regime, to business as usual, but lower down the institutional ladder, people seem to feel that during the long boom something was missing in their lives: the connections and bonds forged at work.

Although those are fine reasons to dismiss loyalty, as I know from experience, I’d like to suggest another reason we are seeing so much disloyalty, namely that people see through the meaningless of their job, and are wondering why the system has even been set up this way in the first place.

In other words, I don’t think a better hierarchy and super smart bosses in finance is going to make back office people gung-ho. I think that the credit crisis has clearly exposed what people already suspected, namely that they are working hard but not accomplishing much. If we want people to feel fulfilled, wouldn’t it make more sense to work less, and spend more time off with their families and their thoughts? Could we as a society imagine something like that?

A rising tide lifts which boats?

My friend Jordan Ellenberg has a really excellent blog post over at Quomodocumque, which is one of my favorite blogs in that it combines hard-core math nerdiness with funny observations about how much the Baltimore Orioles stink (among other things).

In his post he talks about an anti-#OWS article called “The Occupy movement has it all wrong”, by Larry Kaufman, recently published in a Madison, WI newspaper called Isthmus.

Specifically, in that article, Kaufman tries to use the old saying “a rising tide lifts all boats” to argue that most people (in fact, 81% of them) are better off than their parents were. What’s awesome about Jordan is that he goes to the source, a Scott Winship article, and susses out the extent to which that figure is true. Turns out it’s kind of true with a certain way of weighting numbers depending on how many kids there are in the family and because so many women have started working in the past 40 years. Jordan’s conclusion:

So yes: almost all present adults have more money than their parents did. And how did they accomplish this? By having one or two kids instead of three or four, and by sending both parents to work outside the home. Now it can’t be denied that a society in which most familes have two income-earning parents, and the business-hours care of young children is outsourced to daycare and preschool, is more productive from the economic point of view. And I, who grew up with a single sibling and two working parents and went to plenty of preschool, find it downright wholesome. But it is not the kind of development political conservatives typically celebrate.

Another thing that Jordan tears apart from the article is that the original source specifically pointed out stuff that Kaufman seems to have missed, given his political agenda:

Winship also emphasizes the finding that children in Canada and Western Europe have an easier time moving out of poverty than Americans do. This part is absent from Kaufmann’s piece. Maybe he didn’t have the space. Maybe it’s because a comparison with higher-tax economies would make some trouble for his confident conclusion: “the punitive redistribution policies favored by Occupy Madison will divert capital away from productive initiatives that enhance growth and earnings opportunities for all, while doing nothing to build the stable families and “bottom-up” capabilities that are particularly important for helping the poorest Americans escape poverty.”

When the Isthmus is running a more doctrinaire GOP line on poverty than the National Review, the alternative press has arrived at a very strange place indeed.

Go, Jordan!

Let’s go back to that phrase “a rising tide lifts all boats”. It was the basis of Kaufman’s argument, and as Jordan points out was a pretty weak basis, in that the lift was arguable gotten only through sacrifice. But my question is, is that a valid argument to make anyway?

Let’s examine this metaphor a bit. When we think about it positively, and imagine something like the housing bubble which elevated many people’s net worth (ignoring the people who weren’t home owners at all during that time), we can see why “a rising tide lifts all boats” is a good thing: we want the generic imaginary person to do well, and we’re all happy for them to do well.

However, if we turn that phrase around in a negative moment, it’s really not clearly a good perspective. Let’s try it: “an ebbing tide lowers all boats”. Take the example of a housing crash analogously to the above. Firstly it’s not true, since for those people who couldn’t afford housing in the bubble, a more reasonable housing market is a good thing (for some reason people keep forgetting this). Secondly, when we are thinking about lowered boats we worry about those people whose boats are lowered. Who are those people? How much have they lost? Will they be okay?

The answers are, they are the people who were barely able to own the house in the good times. They’ve lost everything. They aren’t okay.

It’s a nearly vapid phrase when you think about it, but it’s used by conservatives a lot to justify policies that only work well in good times.

I’d argue that the real question we should be asking isn’t whether we are all sailing away in boats but how much risk we take on as individuals. I will go into this further in another post, but the gist is that, instead of the unit of measurement being assumed to be dollars, I’d like to reframe the concept of economic health in terms of a unit of risk. Risk is harder to measure than dollars, and there are lots of different kinds of risk, but even so it’s a worthy exercise.

For example, in the housing boom we had people who could barely afford a house get into ridiculous mortgage contracts, with resetting usurious interest rates. They were taking on enormous amounts of risk, in this case risk of being foreclosed on and losing their home. By contrast, people who were well-off at the start of the housing boom are for the most part still well off. There was very little risk for them.

I’d like to offer up an alternative phrase which would capture the risk perspective. Something like, “we should make sure everyone’s boats are water tight and firmly moored to the pier”. Not nearly as catchy, I know. But to make for it I’m linking to this related video called I’m On a Boat. I’ve actually been looking for excuses to link to this for a while. Here’s a kind of awesome picture from the video:

Where is Volcker’s letter? (#OWS)

At the Alternative Banking working group we are working on publicly commenting on the proposed Volcker Rule. Check out this blog post which addresses the exemption for repos. Keeping in mind that repos brought down MF Global a few weeks ago, this is a hot topic.

Here’s another hot topic, at least to me. Who has a copy of Volcker’s original 3-page letter? The published rumor has it that he wrote a 3-page letter to Obama outlining the goal of the regulation, but I can’t find it anywhere. I do have this quote from Volcker about the proposed 550 page behemoth (taken from a New York Times article):

“I’d write a much simpler bill. I’d love to see a four-page bill that bans proprietary trading and makes the board and chief executive responsible for compliance. And I’d have strong regulators. If the banks didn’t comply with the spirit of the bill, they’d go after them.” – Volcker

Also from the New York Times, a column of Simon Johnson’s on the Volcker rule and what it’s missing.

If anyone knows how to get their hands on the original letter, please tell me, I’d really love to see it. Maybe someone knows Volcker and can just ask him for a copy?