Archive

The Lede Program has started!

Yesterday was the first day of the Lede Program and so far so awesome. After introducing ourselves – and the 17 students are each amazing – we each fired up an EC2 server on the Amazon cloud (in North Virginia) and cloning a pre-existing disc image, we got an inspiration speech from Matt Jones about technological determinism and the ethical imperative of reproducibility. Then Adam Parrish led the class in a fun “Hello, world!” exercise on the iPython notebook. In other words, we rocked out.

Today we’ll hear from Soma about some bash command line stuff, file systems, and some more basic python. I can’t wait. Our syllabi are posted on github.

The Future of Data Journalism, I hope

I’m really excited about the Lede Program I’ve been working on at the Journalism School at Columbia. We’ve just now got a full and wonderful faculty and a full pilot class of 16 brilliant and excited students.

So now that we’ve gotten set up, what are we going to do?

Well, the classes are listed here, but let me say it in a few words: for the first half of the summer, we’re going to to teach the students how to use data and build models in context. We’ll teach them to script in python and use github for their code and homework. We’ll teach them how to use API’s, how to scrape data when there are no API’s, and by the end of the first half of the summer they will know how to build their own API. They will submit projects in iPython notebooks to meet the highest standard of reproducibility and transparency.

In the second half of the summer, they will learn more about algorithms, on the one hand, and how deeply to distrust algorithms, on the other. I’ll be teaching them a class invented by Mark Hansen which he called “the Platform”:

This begins with the idea that computing tools are the products of human ingenuity and effort. They are never neutral and they carry with them the biases of their designers and their design process. “Platform studies” is a new term used to describe investigations into the relationships between computing technologies and the creative or research products they help generate. How do you understand how data, code and algorithm affect creative practices can be an effective first step toward critical thinking about technology? This will not be purely theoretical, however, and specific case studies (technologies) and project work will make the ideas concrete.

In order to teach this I’ll need lots of guest lecturers on bias and in particular the politics behind modeling. Emanuel Derman has kindly offered to give one of the first guest lectures. Please suggest more!

Now, it’s easier to criticize than it is to create, and I don’t want to train a whole generation of journalists that they should just swear off mathematical modeling altogether. But I do want to make sure they are skeptical and understand the need for robustness and transparency. For that reason I’m also looking for great examples of reproducible data journalism (please provide them!).

For example, this is a great video, but where are the calculations that have been made that support it? And what assumptions went into it?

In other words, to make this a truly great video, we would need to be able to scrutinize those calculations and for that matter the data sources and the data. Then we could have a conversation about under what conditions private companies should be allowed to rely on food stamp programs for their workers.

Now I’m not claiming that all journalism is necessarily data journalism. Sometimes we’re simply talking about one person with one set of facts around them, and that’s also hugely important. For example, and in the same vein as the above video, take a look at this Reuters blog post written by Danish McDonalds worker and activist Louis Marie Rantzau who earns $21 per hour and has great benefits. Pretty much all you need to know is that she exists.

So here’s what I hope: that we start having conversations that are somewhat more based on evidence, which relies crucially on a separate discussion about what constitutes evidence. I’m hoping that we stop hiding misleading arguments behind opaque calculations and start talking about which assumptions are valid, and why we chose one model or algorithm over another, and how sensitive the conclusions are to different reasonable assumptions. I hope that, as we share our code and try out different approaches, we find ourselves acknowledging certain ground-level truths that we can agree on and then – not that we’ll stop arguing – but we might better understand why we disagree on other things.

On Slate Money Podcast starting Saturday

There has been very little press that I can find but if you look reeeeally closely you’ll see this recent article from the New York Times, with the following line:

The digital magazine Slate will start two new podcasts in the next week: The Gist, with the former NPR reporter Mike Pesca, its first daily podcast intended to deliver news and opinion to afternoon drive-time listeners, and Money, hosted by the financial writer Felix Salmon.

And moreover, here’s a suggestion, if you squint your eyes a wee bit, you might notice that I’m actually working with Felix Salmon and Jordan Weissman on the Money podcast, starting this Saturday.

And look, I don’t listen to podcasts – yet – but maybe you do, so I thought you might like to know. I’m looking forward to doing this because it’s fun and forces me to think about various interesting topics.

The Lede Program has awesome faculty

A few weeks ago I mentioned that I’m the Program Director for the new Lede Program at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. I’m super excited to announce that I’ve found amazing faculty for the summer part of the program, including:

- Jonathan Soma, who will be the primary instructor for Basic Computing and for Algorithms

- Dennis Tenen, who will be helping Soma in the first half of the summer with Basic Computing

- Chris Wiggins, who will be helping Soma in the second half of the summer with Algorithms

- An amazing primary instructor for Databases who I will announce soon,

- Matthew Jones, who will help that amazing yet-to-be-announced instructor in Data and Databases

- Three amazing TA’s: Charles Berret, Sophie Chou, and Josh Vekhter (who doesn’t have a website!).

I’m planning to teach The Platform with the help of a bunch of generous guest lecturers (please make suggestions or offer your services!).

Applications are open now, and we’re hoping to get amazing students to enjoy these amazing faculty and the truly innovative plan they have for the summer (and I don’t use the word “innovative” lightly!). We’ve already gotten some super strong applications and made a couple offers of admission.

Also, I was very pleased yesterday to see a blogpost I wrote about the genesis and the goals of the program be published in PBS’s MediaShift.

Finally, it turns out I’m a key influencer, according to The Big Roundtable.

Let’s experiment more

What is an experiment?

The gold standard in scientific fields is the randomized experiment. That’s when you have some “treatment” you want to impose on some population and you want to know if that treatment has positive or negative effects. In a randomized experiment, you randomly divide a population into a “treatment” group and a “control group” and give the treatment only to the first group. Sometimes you do nothing to the control group, sometimes you give them some other treatment or a placebo. Before you do the experiment, of course, you have to carefully define the population and the treatment, including how long it lasts and what you are looking out for.

Example in medicine

So for example, in medicine, you might take a bunch of people at risk of heart attacks and ask some of them – a randomized subpopulation – to take aspirin once a day. Note that doesn’t mean they all will take an aspirin every day, since plenty of people forget to do what they’re told to do, and even what they intend to do. And you might have people in the other group who happen to take aspirin every day even though they’re in the other group.

Also, part of the experiment has to be well-defined lengths and outcomes of the experiment: after, say, 10 years, you want to see how many people in each group have a) had heart attacks and b) died.

Now you’re starting to see that, in order for such an experiment to yield useful information, you’d better make sure the average age of each subpopulation is about the same, which should be true if they were truly randomized, and that there are plenty of people in each subpopulation, or else the results will be statistically useless.

One last thing. There are ethics in medicine, which make experiments like the one above fraught. Namely, if you have a really good reason to think one treatment (“take aspirin once a day”) is better than another (“nothing”), then you’re not allowed to do it. Instead you’d have to compare two treatments that are thought to be about equal. This of course means that, in general, you need even more people in the experiment, and it gets super expensive and long.

So, experiments are hard in medicine. But they don’t have to be hard outside of medicine! Why aren’t we doing more of them when we can?

Swedish work experiment

Let’s move on to the Swedes, who according to this article (h/t Suresh Naidu) are experimenting in their own government offices on whether working 6 hours a day instead of 8 hours a day is a good idea. They are using two different departments in their municipal council to act as their “treatment group” (6 hours a day for them) and their “control group” (the usual 8 hours a day for them).

And although you might think that the people in the control group would object to unethical treatment, it’s not the same thing: nobody thinks your life is at stake for working a regular number of hours.

The idea there is that people waste their last couple of hours at work and generally become inefficient, so maybe knowing you only have 6 hours of work a day will improve the overall office. Another possibility, of course, is that people will still waste their last couple of hours of work and get 4 hours instead of 6 hours of work done. That’s what the experiment hopes to measure, in addition to (hopefully!) whether people dig it and are healthier as a result.

Non-example in business: HR

Before I get too excited I want to mention the problems that arise with experiments that you cannot control, which is most of the time if you don’t plan ahead.

Some of you probably ran into an article from the Wall Street Journal, entitled Companies Say No to Having an HR Department. It’s about how some companies decided that HR is a huge waste of money and decided to get rid of everyone in that department, even big companies.

On the one hand, you’d think this is a perfect experiment: compare companies that have HR departments against companies that don’t. And you could do that, of course, but you wouldn’t be measuring the effect of an HR department. Instead, you’d be measuring the effect of a company culture that doesn’t value things like HR.

So, for example, I would never work in a company that doesn’t value HR, because, as a woman, I am very aware of the fact that women get sexually harassed by their bosses and have essentially nobody to complain to except HR. But if you read the article, it becomes clear that the companies that get rid of HR don’t think from the perspective of the harassed underling but instead from the perspective of the boss who needs help firing people. From the article:

When co-workers can’t stand each other or employees aren’t clicking with their managers, Mr. Segal expects them to work it out themselves. “We ask senior leaders to recognize any potential chemistry issues” early on, he said, and move people to different teams if those issues can’t be resolved quickly.

Former Klick employees applaud the creative thinking that drives its culture, but say they sometimes felt like they were on their own there. Neville Thomas, a program director at Klick until 2013, occasionally had to discipline or terminate his direct reports. Without an HR team, he said, he worried about liability.

“There’s no HR department to coach you,” he said. “When you have an HR person, you have a point of contact that’s confidential.”

Why does it matter that it’s not random?

Here’s the crucial difference between a randomized experiment and a non-randomized experiment. In a randomized experiment, you are setting up and testing a causal relationship, but in a non-randomized experiment like the HR companies versus the no-HR companies, you are simply observing cultural differences without getting at root causes.

So if I notice that, at the non-HR companies, they get sued for sexual harassment a lot – which was indeed mentioned in the article as happening at Outback Steakhouse, a non-HR company – is that because they don’t have an HR team or because they have a culture which doesn’t value HR? We can’t tell. We can only observe it.

Money in politics experiment

Here’s an awesome example of a randomized experiment to understand who gets access to policy makers. In an article entitled A new experiment shows how money buys access to Congress, an experiment was conducted by two political science graduate students, David Broockman and Josh Kalla, which they described as follows:

In the study, a political group attempting to build support for a bill before Congress tried to schedule meetings between local campaign contributors and Members of Congress in 191 congressional districts. However, the organization randomly assigned whether it informed legislators’ offices that individuals who would attend the meetings were “local campaign donors” or “local constituents.”

The letters were identical except for those two words, but the results were drastically different, as shown by the following graphic:

Conducting your own experiments with e.g. Mechanical Turk

You know how you can conduct experiments? Through an Amazon service called Mechanical Turk. It’s really not expensive and you can get a bunch of people to fill out surveys, or do tasks, or some combination, and you can design careful experiments and modify them and rerun them at your whim. You decide in advance how many people you want and how much to pay them.

So for example, that’s how then-Wall Street Journal journalist Julia Angwin, in 2012, investigated the weird appearance of Obama results interspersed between other search results, but not a similar appearance of Romney results, after users indicated party affiliation.

Conclusion

We already have a good idea of how to design and conduct useful and important experiments, and we already have good tools to do them. Other, even better tools are being developed right now to improve our abilities to conduct faster and more automated experiments.

If we think about what we can learn from these tools and some creative energy into design, we should all be incredibly impatient and excited. And we should also think of this as an argumentation technique: if we are arguing about whether a certain method or policy works versus another method or policy, can we set up a transparent and reproducible experiment to test it? Let’s start making science apply to our lives.

An Interview And A Notebook

Interview on Junk Charts

Yesterday I was featured on Kaiser Fung’s Junk Charts blog in an interview where he kindly refers to me as a “Numbersense Pro”. Previous to this week, my strongest connection with Kaiser Fung was through Andrew Gelman’s meta-review of my review and Kaiser’s review of Nate Silver’s book The Signal And The Noise.

iPython Notebook in Data Journalism

Speaking of Nate Silver, Brian Keegan, a quantitative social scientist from Northeastern University, recently built a very cool iPython notebook (hat tip Ben Zaitlen), replete with a blog post in markdown on the need for openness in journalism (also available here), which revisited a fivethirtyeight article originally written by Walt Hickey on the subject of women in film. Keegan’s notebook is truly a model of open data journalism, and the underlying analysis is also interesting, so I hope you have time to read it.

The Lede Program: An Introduction to Data Practices

It’s been tough to blog what with jetlag and a new job, and continuing digestive issues stemming from my recent trip, which has prevented me from drinking coffee. It really isn’t until something like this happens that I realize how very much I depend on caffeine for my early morning blogging. I really cherish that addiction like a child. Don’t tell my other kids.

Speaking of my new job, the website for the Lede Program: An Introduction to Data Practices is now live, as is the application. Very cool.

We’re holding information sessions about the program next Monday and Thursday at 1:00pm at the Stabile Center, on the first floor of the Journalism School which is in Pulitzer Hall. Please join us and please spread the news.

We are also still looking for teachers for the program, and we’ve fixed the summer classes, which will be:

- Basic computing,

- Data and databases,

- Algorithms, and

- The platform

I’m really excited about all of these but probably most about the last one, where we will investigate biases inherent in data, systems, and platforms and how they affect our understanding of objective truth. Please tell me if you know someone who might be great for teaching any of these, they are intense, seven week classes (either from end of may to mid-July or from mid-July to the end of August) which will meet 3 hours twice a week each.

Working at the Columbia Journalism School

I’m psyched to say that, as of today, I’m helping start a data journalism program at the Columbia J-School. It’s a one or two semester post-bacc program to get people into data, coding, and visualizations who are starting from non-technical fields. It starts this summer and runs through the end of the year.

And although it’s being held in the J-School, it’s not only meant for journalists. The idea is that people from other humanities who see value in working with data can enroll in the program and emerge competent with data.

There’s no time to waste, as the program starts soon (May 27th) and we don’t even quite have a name for it (suggestions welcome!). We’re also looking for students and teachers. What we do have is plenty of great plans of what to teach, lots of institutional support, and some scholarship money.

Exciting!

Julia Angwin’s Dragnet Nation

I recently devoured Julia Angwin‘s new book Dragnet Nation: A Quest for Privacy, Security, and Freedom in a World of Relentless Surveillance. I actually met Julia a few months ago and talked to her briefly about her upcoming book when I visited the ProPublica office downtown, so it was an extra treat to finally get my hands on the book.

First off, let me just say this is an important book, and a provides a crucial and well-described view into the private data behind the models that I get so worried about. After reading this book you have a good idea of the data landscape as well as many of the things that can currently go wrong for you personally with the associated loss of privacy. So for that reason alone I think this book should be widely read. It’s informational.

Julia takes us along her journey of trying to stay off the grid, and for me the most fascinating parts are her “data audit” (Chapter 6), where she tries to figure out what data about her is out there and who has it, and the attempts she makes to clean the web of her data and generally speaking “opt out”, which starts in Chapter 7 but extends beyond that when she makes the decision to get off of gmail and LinkedIn. Spoiler alert: her attempts do not succeed.

From the get go Julia is not a perfectionist, which is a relief. She’s a working mother with a web presence, and she doesn’t want to live in paranoid fear of being tracked. Rather, she wants to make the trackers work harder. She doesn’t want to hand herself over to them on a silver platter. That is already very very hard.

In fact, she goes pretty far, and pays for quite a few different esoteric privacy services; along the way she explores questions like how you decide to trust the weird people who offer those services. At some point she finds herself with two phones – including a “burner”, which made me think she was a character in House of Cards – and one of them was wrapped up in tin foil to avoid the GPS tracking. That was a bit far for me.

Early on in the book she compares the tracking of a U.S. citizen with what happened under Nazi Germany, and she makes the point that the Stasi would have been amazed by all this technology.

Very true, but here’s the thing. The culture of fear was very different then, and although there’s all this data out there, important distinctions need to be made: both what the data is used for and the extent to which people feel threatened by that usage are very different now.

Julia brought these up as well, and quoted sci-fi writer David Brin: The key question is, who has access? and what do they do with it?

Probably the most interesting moment in the book was when she described the so-called “Wiretapper’s Ball”, a private conference of private companies selling surveillance hardware and software to governments to track their citizens. Like maybe the Ukrainian government used such stuff when they texted warning messages to to protesters.

She quoted the Wiretapper’s Ball organizer Jerry Lucas as saying “We don’t really get into asking, ‘Is in the public’s interest?'”.

That’s the closest the book got to what I consider the critical question: to what extent is the public’s interest being pursued, if at all, by all of these data trackers and data miners?

And if the answer is “to no extent, by anyone,” what does that mean in the longer term? Julia doesn’t go much into this from an aggregate viewpoint, since her perspective is both individual and current.

At the end of the book, she makes a few interesting remarks. First, it’s just too much work to stay off the grid, and moreover it’s become entirely commoditized. In other words, you have to either be incredibly sophisticated or incredibly rich to get this done, at least right now. My guess is that, in the future, it will be more about the latter category: privacy will be enjoyed only by those people who can afford it.

Julia also mentions near the end that, even though she didn’t want to get super paranoid, she found herself increasingly inside a world based on fear and well on her way to becoming a “data survivalist,” which didn’t sound pleasant. It is not a lot of fun to be the only person caring about the tracking in a world of blithe acceptance.

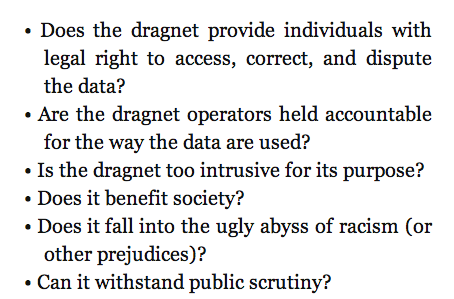

Julia had some ways of measuring a tracking system, which she refers to as a “dragnet”, which seems to me a good place to start:

Data journalism

I’m in Berkeley this week, where I gave two talks (here are my slides from Monday’s talk on recommendation engines, and here are my slides from Tuesday’s talk on modeling) and I’ve been hanging out with math nerds and college friends and enjoying the amazing food and cafe scene. This is the freaking life, people.

Here’s what’s been on my mind lately: the urgent need for good data journalism. If you read this Washington Post blog by Max Fisher you will get at one important angle of the problem. The article talks about the need for journalists to be competent in basic statistics and exploratory data analysis to do reasonable reporting on data, in this case the state of journalistic freedoms.

And you might think that, as long as journalists report on other stuff that’s not data heavy, they’re safe. But I’d argue that the proliferation of data is leaking into all corners of our culture, and basic data and computing literacy is becoming increasingly vital to the job of journalism.

Here’s what I’m not saying (a la Miss Disruption): learn to code, journalists, and everything will be cool. To be clear, having data skills is necessary but not sufficient.

So it’s more like, if you don’t learn to code, and even more importantly if you don’t learn to be skeptical of the models and the data, then you will have yet another obstacle between you and the truth.

Here’s one way to think about it. A few days ago I wrote a post about different ways to define and regulate discriminatory acts. On the one hand you have acts or processes that are “effectively discriminatory” and on the other you have acts or processes that are “intentionally discriminatory.”

In this day and age, we have complicated, opaque, and proprietary models: in other words, a perfect hiding place for bad intentions. It would be idiotic for someone with the intention of being discriminatory to do so outright. It’s much easier to embed such a thing in an opaque model where it will seem unintentional and will probably never be discovered at all.

But how is an investigative journalist going to even approach that? The first thing they need is to arm themselves with the right questions and the right attitude. And it wouldn’t help if they or their team can perform a test on the data and algorithm as well.

I’m not saying that we’re going to suddenly have do-everything super human journalists. Just as the list of job requirements for data scientists is outrageously long and nobody can be expert at everything, we will have to form teams of journalists which as a whole has lots of computing and investigative expertise.

The alternative is that the models go unchallenged, which is a really bad idea.

Here’s a perfect example of what I think needs to happen more: when ProPublica reverse-engineered Obama’s political messaging model.