Three Ideas for defusing Weapons of Math Destruction

This is a guest post by Kareem Carr, a data scientist living in the Cambridge. He’s a fellow at Harvard’s Institute of Quantitative Social Science and an associate computational biologist at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. Formerly, he has held positions at Harvard’s Molecular and Cellular Biology Department and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

When your algorithms can potentially affect the way physicians treat their dying patients, it really brings home how critical it is to do data science right. I work at a biomedical research institute where I study cancer data and ways of using it to help make better decisions. It’s a tremendously rewarding experience. I get the chance to apply data science on a massive scale and in a socially relevant way. I am passionate about the ways in which we can use automated decision processes for social good and I spend the vast majority of my time thinking about data science.

A year ago, I started working on creating a framework for assessing performance of an algorithm used heavily in cancer research. The first part of the project involved gathering all the data that we could get our hands on. The datasets had been created by different processes and had various advantages and disadvantages. First, the most valued but labor-intensive category of datasets to create had been manually curated by multiple people. More plentiful were datasets that had not been manually curated, but had been assessed by so many different algorithms that they were considered extremely well-characterized. Finally, there were the artificial datasets that had been created by simulation and for which the truth was known, but which lacked the complexity and depth of real data. Each type of dataset required careful consideration of the type of evidence it provided for proper algorithm performance. I came to really understand that validation of an algorithm and characterization of the typical errors were an essential part of the data science. The project taught me a few lessons that I think might be generally applicable.

Use open datasets

In most cases, it is preferable that algorithms be open-source and available for all to examine. If algorithms must be closed-source and proprietary, then open, curated datasets are essential for comparisons among algorithms. These may include real data that has been cleared for general use, anonymized data or high-quality artificial data. Open datasets allow us to analyze algorithms even when they are too complex to understand or when the source code is hidden. We can observe where and when they make errors and discern patterns. We can determine in what circumstances other algorithms can be better. This insight can be extremely powerful when it comes to applying algorithms in the real world.

Take manual curation seriously

Domain-specific experts, such as doctors in medicine or coaches in sports, are generally a very powerful source of information. Panels of experts are even better. While humans are by no means perfect, when careful consideration of an algorithmic result by experts implies that the algorithm has failed, it’s important to take that message seriously. It’s important to investigate if and why the algorithm failed. Even if the problem is never fixed, it is important to understand the types of errors the algorithm makes and to measure its failure rate in various circumstances.

Demand causal models

While it has become very easy to build systems which generate high-performing black-box algorithms, we must push for explainable results wherever possible. Furthermore, we should demand truly causal models rather than the merely predictive. Predictive models perform well when there are no external modifications of the system. Causal models continue to be accurate despite exogenous shocks and policy interventions. Frequently, we create the former, yet try to deploy them as if they are the latter with disastrous consequences.

All three principles have one underlying idea. Bad data science obscures and ignores the real world performance of its algorithms. It relies on little to no validation. When it does perform validation, it relies on canned approaches to validation. It doesn’t critically examine instances of bad performance with an eye towards trying to understand how and why these failures occur. It doesn’t make the nature of these failures widely known so consumers of these algorithms can deploy them with discernment and sophistication.

Good data science does the opposite. It creates algorithms which are deeply and widely understood. It allows us to understand when algorithms fail and how to adapt to those failures. It allows us to intelligently interpret the results we receive. It leads to better decision making.

Let’s stop the proliferation of weapons of math destruction with better data science!

Sketchy genetic algorithms are the worst

Math is intimidating. People who meet me and learn that I have a Ph.D. in math often say, “Oh, I suck at math.” It’s usually half hostile, because they’re not proud of this fact, and half hopeful, like they want to believe I must be some kind of magician if I’m good at it, and I might share my secrets.

Then there’s medical science, specifically anything around DNA or genetics. It’s got its own brand of whiz-bang magic and intimidation. I know because, in this case, I’m the one who is no expert, and I kind of want anything at all to be true of a “DNA test.” (You can figure out everything that might go wrong and fix it in advance? Awesome!)

If you combine those two things, you’ve basically floored almost the entire population. They remove themselves from even the possibility of critique.

That’s not always a good thing, especially when the object under discussion is an opaque and possibly inaccurate “genetic algorithm” that is in widespread use to help people make important decisions. Today I’ve got two examples of this kind of thing.

DNA Forensics Tests

The first example is something I mentioned a while ago, which was written up beautifully in the Atlantic by Matthew Shaer. Namely, DNA forensics.

There seem to be two problems in this realm. First, there’s a problem around contamination. The tests have gotten so sensitive that it’s increasingly difficult to know if the DNA being tested comes from the victim of a crime, the perpetrator of the crime, the forensics person who collected the sample, or some random dude who accidentally breathed in the same room three weeks ago. I am only slightly exaggerating.

Second, there’s a problem with consistency. People claiming to know how to perform such tests get very different results from other people claiming to know how to perform them. Here’s a quote from the article that sums up the issue:

“Ironically, you have a technology that was meant to help eliminate subjectivity in forensics,” Erin Murphy, a law professor at NYU, told me recently. “But when you start to drill down deeper into the way crime laboratories operate today, you see that the subjectivity is still there: Standards vary, training levels vary, quality varies.”

Yet, the results are being used to put people away. In fact jurors are extremely convinced by DNA evidence. From the article:

A researcher in Australia recently found that sexual-assault cases involving DNA evidence there were twice as likely to reach trial and 33 times as likely to result in a guilty verdict; homicide cases were 14 times as likely to reach trial and 23 times as likely to end in a guilty verdict.

Opioid Addiction Risk

The second example I have today comes from genetic testing of “opioid addiction risk.” It was written up in Medpage Today by Kristina Fiore, and I’m pretty sure someone sent it to me but I can’t figure out who (please comment!).

The article discusses two new genetic tests, created by companies Proove and Canterbury, which claim to accurately assess a person’s risk of becoming addicted to pain killers.

They don’t make their accuracy claims transparent (93% for Proove), and scientists not involved with the companies peddling the algorithms are skeptical for all sorts of reasonable reasons, including historical difficulty reproducing results like this.

Yet they are still being marketed as a way of saving money on worker’s comp systems, for example. So in other words, people in pain who are rated “high risk” might be denied pain meds through such a test that has no scientific backing but sounds convincing.

Enough with this intimidation. We need new standards of evidence before we let people wield scientific tools against people.

Sentencing more biased by race than by class

Yesterday I was super happy to be passed along this amazing blogpost from lawyerist.com called Uncovering Big Bias with Big Data and written by David Colarusso, a lawyer who became a data scientist (hat tip Emery Snyder).

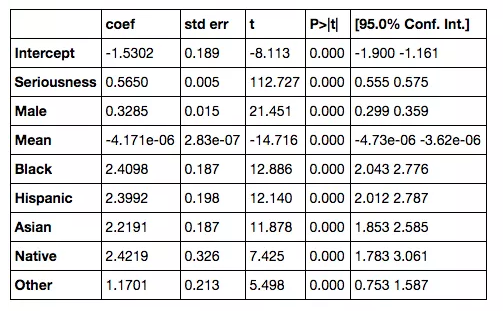

For the article, David mines a recently opened criminal justice data set from Virginia, and asked the question, what affects the length of sentence more: income or race? His explanation of each step is readable by non-technical people, it’s a real treasure.

And, unsurprisingly to those of us who have thought about this, the answer he came up with is race, by a long margin, although he also found that class matters too.

In particular he fit his data with the outcome variable set to length of sentence in days – or rather, log(1 + that term), which he explains nicely – and he chose the attributes to be the gender of the defendant, a bunch of indicator variables to determine the race of the defendant (one for each race except white, which was the “default race,” which I thought was a nice touch), the income of the defendant, and finally the “seriousness of the charge,” a system which he built himself and explains. He gives a reasonable explanation of all of these choices except for the gender.

His conclusion:

For a black man in Virginia to get the same treatment as his Caucasian peer, he must earn more than

half a million dollars$90,000 a year.

This sentence follows directly from staring at this table for a couple of minutes, if you imagine two defendants with the same characteristics except one is white and the other is black:

It’s simplistic, and he could have made other choices, but it’s a convincing start. Don’t trust me though, take a look at his blogpost, and also his github code which includes his iPython notebook.

I am so glad people are doing this. Compared to shitty ways of using data, which end up doubling down on poor and black folks, this kind of analysis shines a light on how the system works against them, and gives me hope that one day we’ll fix it.

Teacher growth score “capricious” and “arbitrary”, judge rules

Holy crap, peoples! I’m feeling extremely corroborated this week, what with the ProPublica report on Monday and also the recent judge’s ruling on a teacher’s growth score. OK, so technically the article actually came out last week (hat tip Chris Wiggins), but I only found out about it yesterday.

Growth scores are in the same class of models as Value-added models, and I’ve complained about them at great length in this blog as well as in my upcoming book.

Here’s what happened. A teacher named Sheri Lederman in Great Neck, New York got a growth score of 14 one year and 1 the next, even though her students did pretty well on state tests in both years.

Lederman decided to sue New York State for her “ineffective rating”, saying it was a problem of the scoring system, not her teaching. Albany Supreme Court justice Roger McDonough got the case and ruled last week.

McDonough decided to vacate her score, describing it as “arbitrary and capricious”. Here are more details on the ruling, taken from the article:

In his ruling, McDonough cited evidence that the statistical method unfairly penalizes teachers with either very high-performing students or very low-performing students. He found that Lederman’s small class size made the growth model less reliable.

He found an inability of high-performing students to show the same growth using current tests as lower-performing students.

He was troubled by the state’s inability to explain the wide swing in Lederman’s score from year to year, even though her students performed at similar levels.

He was perplexed that the growth model rules define a fixed percentage of teachers as ineffective each year, regardless of whether student performance across the state rose or fell.

This is a great start, hopefully we’ll see less growth models being used in the future.

Update: here’s the text of the decision.

3 Terrible Big Data Ideas

Yesterday was, for some reason, a big day for terrible ideas in the big data space.

First, there’s this article (via Matt Stoller) which explains how Cable One is data mining their customers, and in particular are rating potential customers by their FICO scores. If you don’t have a high enough FICO score, they won’t bother selling you pay-TV.

No wait, that’s not completely fair. Here’s how they put it:

“We don’t turn people away,” Might said, but the cable company’s technicians aren’t going to “spend 15 minutes setting up an iPhone app” for a customer who has a low FICO score.

Second, the Chicago Police Department uses data mining techniques of social media to determine who is in gangs. Then they arrest scores of people on their lists, and finally they tout the accuracy of their list in part because of the percentage of people who were arrested who were also on their list. I’d like to see a slightly more scientific audit of this system. ProPublica?

Finally, and this is absolutely amazing, there’s a extremely terrible new start-up in town called Faception (h/t Ernie Davis). Describing itself as a “Facial Personality Profiling company”, Faception promises to “use science” to figure out who is a terrorist based on photographs. Or, as my friend Eugene Stern snarkily summarized, “personality is influenced by genes, facial features are influenced by genes, therefore facial features can be used to predict personality.”

Here’s a screenshot from their website, I promise I didn’t make this up:

Also, here’s a 2-minute advertisement from their founder:

I think my previous claim that Big Data is the New Phrenology was about a year too early.

ProPublica report: recidivism risk models are racist

Yesterday an exciting ProPublica article entitled Machine Bias came out. Written by Julia Angwin, author of Dragnet Nation, and Jeff Larson, data journalist extraordinaire, the piece explains in human terms what it looks like when algorithms are biased.

Specifically, they looked into a class of models I featured in my upcoming book, Weapons of Math Destruction, called “recidivism risk” scoring models. These models score defendants and give those scores to judges to help them decide how long to sentence them to prison, for example. Higher scores of recidivism are supposed to correlate to a higher likelihood of returning to prison, and people who have been assigned high scores also tend to get sentenced to longer prison terms.

What They Found

Angwin and Larson studied the recidivism risk model called COMPAS. Starting with COMPAS scores for 10,000 criminal defendants in Broward County, Florida, they looked at the difference between who was predicted to get rearrested by COMPAS versus who actually did. This was a direct test of the accuracy of the risk model. The highlights of their results:

- Black defendants were often predicted to be at a higher risk of recidivism than they actually were. Our analysis found that black defendants who did not recidivate over a two-year period were nearly twice as likely to be misclassified as higher risk compared to their white counterparts (45 percent vs. 23 percent).

- White defendants were often predicted to be less risky than they were. Our analysis found that white defendants who re-offended within the next two years were mistakenly labeled low risk almost twice as often as black re-offenders (48 percent vs. 28 percent).

- The analysis also showed that even when controlling for prior crimes, future recidivism, age, and gender, black defendants were 45 percent more likely to be assigned higher risk scores than white defendants.

- Black defendants were also twice as likely as white defendants to be misclassified as being a higher risk of violent recidivism. And white violent recidivists were 63 percent more likely to have been misclassified as a low risk of violent recidivism, compared with black violent recidivists.

- The violent recidivism analysis also showed that even when controlling for prior crimes, future recidivism, age, and gender, black defendants were 77 percent more likely to be assigned higher risk scores than white defendants.

Here’s one of their charts (lower scores mean low-risk):

How They Found It

ProPublica is awesome and has the highest standards in data journalism. Which is to say, they published their methodology, including a description of the (paltry) history of other studies that looked into racial differences for recidivism risk scoring methods. They even have the data and the ipython notebook they used for their analysis on github.

They made heavy use of the open records law in Florida to do their research, including the original scores, the subsequent arrest records, and the classification of each person’s race. That data allowed them to build their analysis. They tracked both “recidivism” and “violent recidivism” and tracked both the original scores and the error rates. Take a look.

How Important Is This?

This is a triumph for the community of people (like me!) who have been worrying about exactly this kind of thing but who haven’t had hard proof until now. In my book I made multiple arguments for why we should expect this exact result for recidivism risk models, but I didn’t have a report to point to. So, in that sense, it’s extremely useful.

More broadly, it sets the standard for how to do this analysis. The transparency involved is hugely important, because nobody will be able to say they don’t know how these statistics were computed. They are basic questions by which every recidivism risk model should be measured.

What’s Next?

Until now, recidivism risk models have been deployed naively, in judicial systems all across the country, and judges in those systems have been presented with such scores as if they are inherently “fair.”

But now, people deploying these models – and by people I mostly mean Department of Corrections decision-makers – will have pressure to make sure the models are audited for racism before using them. And they can do this kind of analysis in-house with much less work. I hope they do.

Stuff I’m reading this morning

- Astra Taylor looks at the political side of universities as hedge funds and private equity shops.

- This Atlantic piece outlines a WMD that I didn’t know about related to DNA testing. Opaque, widespread algorithms that put the wrong people in jail.

- If you have some extra cash, consider giving to Fair Foods in Boston so they can replace their ancient truck, Old Betty.

- Does this surprise anybody? Pharma “charity” is profitable.

- How much more public manipulation will Facebook get away with before they give some transparency to their algorithm? The answer is: a lot.

- Nice to see trash science debunked. No, breakfast isn’t magical – eat it if you’re hungry, skip it if not.

What is education for?

Say you read something like this article. It’s about yet another failing for-profit college that saddles its students with large debt loads, delivers flawed – possibly useless – education, and graduates fewer than half their students, while making the founders super rich. It’s enough to make you wonder what education is for.

For that matter, I live next door to Columbia University, and for the past week, every day, there have been countless graduations with the requisite ceremonies on campus. Some of them are for things like Columbia college, to be sure, but others are much more confusing. There are countless “cash cow” MA programs at Columbia, with at least 3 in finance alone (one based out of the stats department, one from the math department, and one from the business school). And, whereas we “care about diversity” in many of our college programs, in many of these they are utterly dominated by Chinese kids who get specific STEM versions of student visas that allow them to stay in the U.S. for some months after their program ends.

What’s the actual point to all of this? And I say this as a former director of a post-bac journalism program myself.

And look, I definitely think we taught our students something in that program. But I’m still wondering why exactly we send people to school in such numbers, where 50 years ago we simply didn’t.

Here are some theories, each of which I could make the case for if I were in the mood:

- It’s a way to get these kids edumacated, for them to accumulate important knowledge. This is probably the least likely option.

- It’s a way to socialize our young people and help develop their networks and social skills, so that someday they can call on their friends to deploy insider trading.

- It’s a way to rank all people in the world for future employers.

- It’s a way to give day jobs to people who do important research.

- It’s a way to give day jobs to people who dedicate their time to gaming the US News & World Report college ranking model.

- It’s a way for foreign kids to get American educations and then American jobs.

- It’s a way for colleges to make money and enlarge their brands and endowments.

- It’s a way for companies to avoid training their workers and force them to pay for training before they get offered a job, now that unions have been decimated and nobody stays with a company for more than a few years.

Am I missing something? And is one of these any better an explanation than any other?

White House report on big data and civil rights

Last week the White House issued a report entitled Big Risks, Big Opportunities: the Intersection of Big Data and Civil Rights. Specifically, the authors were United States C.T.O. Megan Smith, Chief Data Scientist DJ Patil, and Cecilia Munoz, who is Assistant to the President and Director of the Domestic Policy Council.

It is a remarkable report, and covered a lot in 24 readable pages. I was especially excited to see the following paragraph in the summary of the report:

Using case studies on credit lending, employment, higher education, and criminal justice, the report we are releasing today illustrates how big data techniques can be used to detect bias and prevent discrimination. It also demonstrates the risks involved, particularly how technologies can deliberately or inadvertently perpetuate, exacerbate, or mask discrimination.

The report itself is broken up into an abstract discussion of algorithms, which for example debunks the widely held assumption that algorithms are objective, discusses problems of biased training data, and discusses problems of opacity, unfairness, and disparate impact. It’s similar in its chosen themes, if not in length, to my upcoming book.

The case studies are well-chosen. Each case study is split into three sections: the problem, the opportunity, and the challenge. They do a pretty good job of warning of things that could theoretically go wrong, if they are spare on examples of how such things are already happening (for such examples, please read my book).

Probably the most exciting part of the report, from my perspective, is in the conclusion, which discusses Things That Should Happen:

Promote academic research and industry development of algorithmic auditing and external testing of big data systems to ensure that people are being treated fairly. One way these issues can be tackled is through the emerging field of algorithmic systems accountability, where stakeholders and designers of technology “investigate normatively significant instances of discrimination involving computer algorithms” and use nascent tools and approaches to proactively avoid discrimination through the use of new technologies employing research-based behavior science. These efforts should also include an analysis identifying the constituent elements of transparency and accountability to better inform the ethical and policy considerations of big data technologies. There are other promising avenues for research and development that could address fairness and discrimination in algorithmic systems, such as those that would enable the design of machine learning systems that constrain disparate impact or construction of algorithms that incorporate fairness properties into their design and execution.

Readers, this is what I want to do with my life, after my book tour. So it’s nice to see people calling for it like this.

Google to stop showing Payday ads

Great news this week for people who have been preyed upon by sketchy online lenders: Google will be cutting off their access to customers through its “AdWords” advertisements (but not its native search).

Specifically, Google’s new AdWords Policy now requires lending advertisers to show their APR is at most 36% and that they do not require loans to be paid back within 60 days.

Some comments:

- This goes into effect on my birthday, July 13th. What a thoughtful present!

- It doesn’t apply to other kinds of loans, even if they’re terrible.

- I’ve read that it is supposed to apply to “lead aggregators” for payday loans but I don’t see in the new policy how that might work. In other words, if the advertiser isn’t offering a loan at all, but is offering to connect people with “great loans,” how does Google check to see what they underlying offers really look like?

- Payday lenders are tricky, and they get around rules all the time to continue their business. For example, take a look at this Washington Post article to see a few ways they might try. How is Google going to keep up with them?

- On the other hand, one of the main ways payday lenders get around state bans on payday lenders is by coming on to people online, and Google is closing off this avenue explicitly, which will really help for people living in New York, for example.

- What I’m leading up to is that Google is leaping over regulators like the CFPB, which kind of makes Google into a quasi-regulator itself. I’m curious as to how it will play out. How many people will be employed by Google to track this stuff down?

- Also, how much money are they walking away from? At least something like $35 million, according to this article. It’s a lot of money but less than 1% of their total revenue.

The payday lending industry, which has a well-paid lobbying arm doing sneaky things, is up in arms, as we might expect. Their argument is along the lines of calling it “discriminatory and a form of censorship,” as if there’s some freedom of speech issue here. There isn’t, since Google is a private platform and can control what it puts on its site.

But there is something interesting going on, if we were to pursue that argument a bit further. Imagine Google ads as a kind of corporate town square, where companies get to broadcast their wares to potential customers. Then, given the nature of targeted online advertising, we should really imagine it as a series of back alleys in which the most vulnerable and desperate individuals, chosen just as much for their zip codes as for their search query, are taken aside and promised their problems will all go away if they just sign on the dotted line.

One last comment. I might be making too much of this, but it feels like a turning point. Instead of just getting rid of truly obvious bad actors (illegal drugs, counterfeit goods, explosives), Google has actually gone further and made a judgement call, and a good one. I’m thinking that means they are starting to acknowledge the responsibility they have to the worst-off of the people who inhabit the environment they create. And that’s a good thing. I hope they get rid of for-profit college ads next.

Algorithms are as biased as human curators

The recent Facebook trending news kerfuffle has made one thing crystal clear: people trust algorithms too much, more than they trust people. Everyone’s focused on how the curators “routinely suppressed conservative news,” and they’re obviously assuming that an algorithm wouldn’t be like that.

That’s too bad. If I had my way, people would have paid much more attention to the following lines in what I think was the breaking piece by Gizmodo, written by Michael Nunez (emphasis mine):

In interviews with Gizmodo, these former curators described grueling work conditions, humiliating treatment, and a secretive, imperious culture in which they were treated as disposable outsiders. After doing a tour in Facebook’s news trenches, almost all of them came to believe that they were there not to work, but to serve as training modules for Facebook’s algorithm.

Let’s think about what that means. The curators were doing their human thing for a time, and they were fully expecting to be replaced by an algorithm. So any anti-conservative bias that they were introducing at this preliminary training phase would soon be taken over by the machine learning algorithm, to be perpetuated for eternity.

I know most of my readers already know this, but apparently it’s a basic fact that hasn’t reached many educated ears: algorithms are just as biased as human curators. Said another way, we should not be offended when humans are involved in a curation process, because it doesn’t make that process inherently more or less biased. Like it or not, we won’t understand the depth of bias of a process unless we scrutinize it explicitly with that intention in mind, and even then it would be hard to make such a thing well defined.

A Call For Riddles

Dear Reader,

You know that riddle about the wolf, the sheep, and the cabbage? You want to bring them across the river in a boat that can only carry one of them at a time, but you can’t leave the sheep and the cabbage alone together because the sheep will eat the cabbage, and you can’t leave the wolf and the sheep alone together because the wolf will eat the sheep.

Anyway, my 7-year-old son loves that riddle, and every night he demands a new riddle as good as that one, and to tell you the truth I don’t know many very good riddles. So today I thought I’d ask you kind readers for your riddles, to help me out with dinner time conversations.

Happy to take links! Maybe there’s a list or a book of great riddles somewhere I don’t know about!

Thanks!

Cathy

p.s. If you google “list of riddles” you come up with something that’s far too sophisticated and involves word play rather than logic. So maybe “riddle” isn’t the right word.

p.p.s. This list is pretty good. I found it by looking for “logic puzzles.”

Math isn’t under attack

Not from airlines afraid of terrorists, anyway.

Since about 15 people have sent me some version of this story about an economist on an airplane, I thought I’d comment briefly on my take.

Namely, it’s mostly due to the lousy reporting, but people have gotten this all wrong. The article’s headline should have read:

Crazy Woman Removed From Plane

because, really, that’s what happened. Some paranoid freak decided that an integral sign on the page of notes of a swarthy Italian man next to her posed a terrorist threat. She passed a note to the flight attendant. The airline took her off the plane. Done.

Well, almost. I mean, they also took the economist off the plane and questioned him, but I’m willing to believe that is absolutely required when terrorist suspicions are thrown around like this insane woman did.

Maybe it’s my inner New Yorker coming out here, but I’m just so used to sitting next to perfectly normal looking people on the subway who turn out to be utterly insane, that I’m ready to assume anyone at all is fucking nuts. And I know I’m not going out on a limb here by mentioning that note-passers older than 13 are already suspect; get up and walk over to someone if you’re worried.

So, short version: some woman was nuts, she indicated as much to the flight crew, and they removed her from the flight. Math isn’t under attack.

Forced Arbitration and the CFPB

This morning I’m studying up on the topic of forced arbitration clauses for my Slate Money podcast. That’s part of the fine print when you sign a corporate contract as a consumer or as an employee which states that you will not sue the company for bullshit they might pull, like unfair fees, no overtime pay, or even discriminatory practices.

What’s more, 90% of the time that “forced arbitration” clause is accompanied by an agreement that you also won’t be part of a class-action lawsuit, if by any chance you’d want to do something to address systemic injustice perpetrated by the corporation.

It’s a massively stacked deck; the calculation of how much it will cost, in terms of lawyers, versus how much you’d get if you won you case means that very few people choose the arbitration option. The arithmetic is particularly cruel since, once class-action suits are out of the way, you’re not even benefitting other people who will come after you and find the same shit being pulled.

And of those consumers or employees who do agree to arbitration, they often lose, partly because the actual arbitration process is much more favorable to corporate lawyers (which the other side has but you don’t) than a typical courtroom.

The process entirely depends on a arbitrator being fair and impartial but, believe it or not, the business in question chooses this person, and often for repeat business, which is to say they have at least indirect influence on the decision if the arbitrator wants more work.

So, here’s the good news. The CFPB has come out with strong rules this week which will render moot such forced arbitration clauses in the case of consumer financial lending products. This is great news, and well-needed, given how many of those contracts were flooded with such unfair fine print:

- credit card issuers 53%

- prepaid cards, 92%

- student loans, 86%

- payday loan 99%

- checking accounts 44%

However, it doesn’t address other kinds of consumer products, and employee situations, that will continue to have these fine print clauses:

- nursing home contracts

- for-profit college contracts

- employee contracts (22% of employees now sign such contracts)

To learn more, take a look at this fine report from the Economic Policy Institute.

Globalization for the 99%

My Occupy group has a new essay posted on Huffington Post, called Globalization for the 99%. The leading paragraph:

As the hard fight over the Trans Pacific Partnership (“TPP”) proceeds, it is important not to confuse the foulness of the TPP’s proposed rules with the otherwise difficult, but not altogether undesirable, prospect of super-national rules of law. To put it bluntly, we should reject the TPP but we should embrace the idea of international cooperation. When we generically decry “globalization”, we are throwing the baby out with the bathwater. We actually want globalization, just not the kind of pro-corporate globalization that we’ve grown to despise. Instead, let’s rethink what good can come from a new notion of globalization that works for the 99%.

Click here for more.

We’re also hosting a Left Forum discussion about this topic, with participants Tamir Rosenblum and The New School for Social Research economics professor Sanjay Reddy. Here’s the abstract:

Occupy’s AltBank (Alternative Banking Group) has proposed a blueprint for international free trade agreements driven by the interests of the global 99% instead of the global 1%. The blueprint will be presented by its author, Tamir Rosenblum. Economist Sanjay Reddy of The New School, specializing in development and international economics, will respond and the discussion will be moderated by mathematician, big-data critic, author and activist Cathy O’Neil.

More information is here, but it will be Sunday, May 22nd at noon, at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 860 11th Ave (Between 58th and 59th) in New York.

Prime Numbers and the Riemann Hypothesis

I just finished reading a neat, new, short (128 pages) book called Prime Numbers and the Riemann Hypothesis by Barry Mazur and William Stein.

Full disclosure: Barry was my thesis advisor and William is a friend of mine, and also a skater.

But anyhoo, the book. It’s really great, I learned a lot reading it, even though I’m supposed to know these things already. But I really didn’t, and now I’m glad I do.

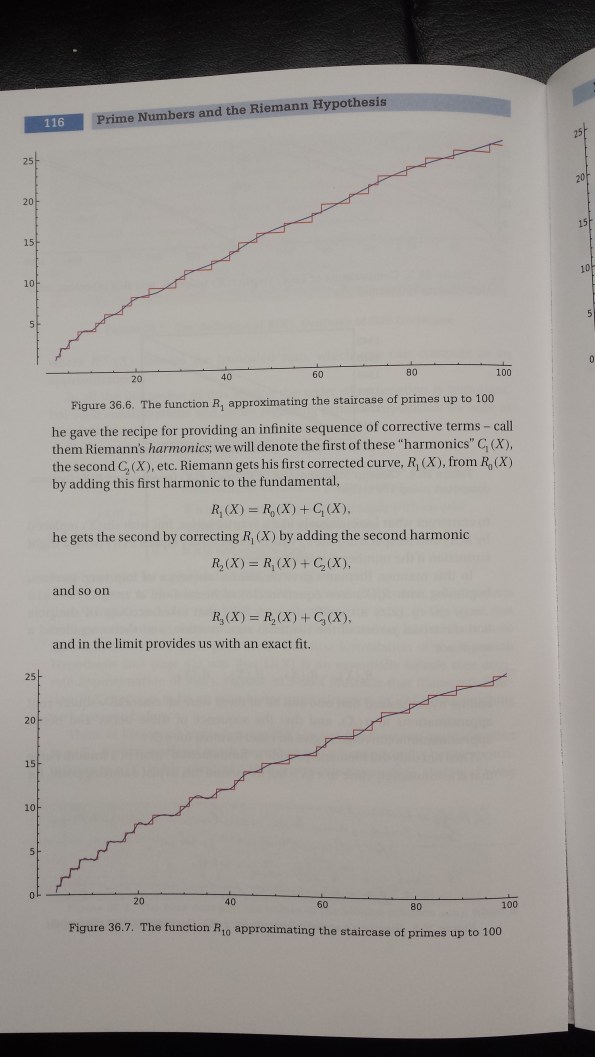

The book doesn’t require a Ph.D. in math to read, though. It is in fact aimed at a person who may have forgotten what the definition of a prime number is. So, there’s a description of the sieve of Eratosthenes as well as the classic proof that there are infinitely many primes.

And, it’s a great combination of authors. True to form for Barry, there are elegant, “pure thought” explanations of deep truths, as well as ample sprinklings of philosophical ruminations. And true to form for William, there are tons of computations that are carried out and expressed graphically, which really help in illustrating what they’re talking about.

And what do they talk about? After describing basic questions about how often primes show up, the discuss such things as:

- what it means for a function to be a good approximation of another function

- Fourier transforms

- Dirac delta “generalized functions” – a seriously good explanation

- The Riemann zeta function and its zeroes, obviously

The book is set up in three parts, conveniently set up so that people who don’t know calculus know when to close the book (although they could also take a detour and read The Cartoon Guide to Calculus instead), or for people who aren’t comfortable in functions of complex variables to skim the last two parts.

Do you know what? The more I think about it, the more I realize that this book does exactly what most general audience books dare not do – including mine – which is to say, they use formulas, and graphs, and generally speaking ask the reader to work hard, in the name of enlightenment, beauty, and wonder.

Technical work for the reader such as this is, normally speaking, something of a third rail. Not in this book. In this book the authors run straight for that rail, set up a game of catch, and invite you to join their picnic in the rain, electric shock be damned. They’re having so much fun that you can’t help yourself.

If I have one complaint it’s all the pictures of white male mathematicians. Yes, I get that they did this work, and this work is amazing, and some of them are my friends, but as an educator I want to be aware of the stereotype threat that this sets up for other readers. I’m still planning to recommend it to people (please read it!) but it would have been even better if it focused on the ideas more and the people less. My two cents.

Fiscal Waterboarding & Ponzi Austerity

Last week I read Yanis Varoufakis’s book, And The Weak Suffer What They Must? Europe’s Crisis and American’s Economic Future. We were expecting Yanis to join us on Slate Money, which he did not end up doing, but I wanted to report on the highlights of the book anyway.

1. “A debt may be a debt but an unpayable debt does not get paid unless it is sensibly restructured.”

Unsurprisingly, Yanis spends a lot of the book talking about debt and debt forgiveness. In particular, he goes into the history of the post-World War II period when Germany’s debt were forgiven, and how critical that was to its growth.

He makes the point that, given that the countries in the Eurozone have no ability to set their currency exchange rates, the deficit countries like Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy have very little power to pay back their debts without either debt forgiveness or a “political union,” which is to say something more like the way the U.S. federal government redistributes money from Massachusetts to Mississippi.

Or, as Yanis put it, “Debt was a symptom of Europe’s awful institutional design, not its problem.”

2. “That monetary union is good for Europe’s economy and consistent with European democracy ought to be a theorem. Europe, however, decided to treat it as an axiom”

Yanis spends the bulk of the book talking about the history of modern monetary policy in Continental Europe, staring with the 1971 “Nixon Shock,” when the US kicked the European currencies off their peg to the dollar and kicked the dollar off the gold standard. This is interesting history which I personally had never learned, and after a few sputters and starts it resulted in the creation of the European Union and the Eurozone.

An interesting point that Yanis makes repeatedly (the book could do with some editing) is that the underlying structures of the European Union and the Eurozone are deeply undemocratic. This maybe seems ok when things are going well and economies seem to be humming along, but in moments of crisis, like we’ve had since 2008, the technocrats basically have all the power, and their decisions regularly and efficiently override the will of the people.

Said another way, the Eurozone was an attempt by Europeans – mostly Germans and French – to make money “apolitical” in the name of the unification of Europe. This was never going to work, according to economists, but the romance of the image was irresistible to many countries.

The one European leader who Yanis credits as seeing this basic problem beforehand is Margaret Thatcher, who was unwilling to join in an earlier version of the Eurozone because of the obvious loss of sovereignty and the lack of democratic influence.

3. “the Bundesbank ensured the European Central Bank would be created in its image, that it would be located in Frankfurt and that it would be designed so as to impose periodic, variable austerity upon weaker economies, including France.”

Yanis spends a lot of time talking about the extent to which Germany is actually in charge of everything going on in the Eurozone, and how rigid and self-interested German bankers are. The first 6 times he mentions this it’s convincing, but after 10 references I started wanting to hear what they’d say.

4. “the Troika is the oligarchs’ and the tax evaders’ best friend”

This wasn’t in the book, but Yanis made an effort while he was Greek’s Finance Minister, to datamine Greek tax returns in order to find tax evaders. He claims this effort, which would have allowed Greece to pay back some of its debt to the rest of Europe, was foiled by the Troika itself.

5. Fiscal Waterboarding & Ponzi Austerity

Yanis is a wordsmith, and he comes up, or at least uses, evocative and memorable phrases to explain complicated political situations. Specifically, he talks about the way the Greeks have been repeatedly bailed out at gunpoint as “fiscal waterboarding,” and the way that the imposed austerity is not only not creating the abundance it was supposedly intended to, but is instead sucking up resources and laying waste to communities, as “Ponzi austerity.”

Speaking of bailouts, Yanis convincingly describes most if not all of the bailouts imposed on Greece as a combination of 1) sending money to German and French banks via Greek taxpayers (and for that matter Irish taxpayers) and 2) kicking the can down the road of the inherent flaws of the Eurozone itself.

The question is, what’s going to happen next? The concept of a political union a la the United States is increasingly unlikely, and the Greek economy is in terrible shape, as we might expect after all this crazy and destined-to-fail austerity.

My guess: the debt is eventually going to be defaulted on, and the Eurozone is going to fall apart, or at the very least lose Greece. My time scale is the next 3 years. The thing I’m worried about is how bad it’s going to get, especially if China also goes bust around the same time.

Book Tour

I’m going through a couple new phases with my upcoming book (available for pre-order now!):

Sorry, I have no more galley copies in my kitchen. They were gone really fast.

Blurbs

This first and current one is “the blurb phase.” That means my publisher has sent out nearly final versions of my book to various fancy people with the hope that they have enough time in their busy lives to read it and write a blurb to go on the back cover.

It’s really an exciting time because we’ve carefully chosen people who probably won’t hate the book. Which is to say, I’ve started to get positive feedback, and not much negative feedback. That’s a nice feeling!

So pretty much I’d like to hold on to this moment for as long as possible, because when the book is reviewed more widely, the critics – at least some of them – will hate the book. That will be tough, but of course I wrote it to be provocative. So I hope my skin is thick enough for that.

Tour

The other thing that’s happening right now, book-wise, is that I’m scheduling a tour for when the book comes out in September. To be precise, the book comes out September 6th, then the tour starts, hopefully after a party, hopefully where my band plays.

So far I think I’m sticking mostly to the East Coast, but I think I have something in San Francisco as well, and perhaps a stop in the midwest in October.

So, readers, what do you think? Are there awesome places I should be sure to visit? People and communities that love books? I have no idea how this all works but I’m guessing I can add stuff if it works with the schedule.

Talking to Yanis Varoufakis on Slate Money this week

Dearest Readers,

Yanis Varoufakis, economist and former Finance Minister of Greece, is currently on a book tour promoting his new book, And the Weak Suffer What They Must? Europe’s crisis, America’s economic future. I’m busy reading it right now.

Why am I telling you this? Because the super exciting news is that he’ll be a guest this week on Slate Money, which means I get to ask him questions.

So, we’ll likely talk about his book, but also timely issues like the situation in Puerto Rico, Brexit, and of course the Greek economy.

Important Confession: I have a celebrity crush on Yanis. And given that, I’m wondering if anyone a bit more level-headed would like to come up with smart questions I should ask him.

Love,

Cathy

p.s. I think Yanis will be in a recording studio in Chicago, so it’s not like I’m going to swoon in person.

p.p.s.

Here’s Yanis killing it with a crazy shirt in the Greek parliament.

Academic Payday Lending Lobbyists

We like to think of academic researchers as fair, objective, and politically neutral. Even though we’ve all seen Inside Job and know not to trust economists, the rest of academia seems relatively safe. Right?

Well, Freakonomics has done some really great research and found evidence that researchers took money from a Payday Lending lobbyist group called Consumer Credit Research Foundation, or CCRF, in return for editing rights of their journal articles (hat tip Ernie Davis).

Here’s a list of academics, only 40% of whom are economists, that took money from CCFR or otherwise had contact with CCFR:

- Jonathan Zinman, an economist at Dartmouth,

- Jennifer Lewis Priestley, professor of data science and statistics at Kennesaw State University in Georgia,

- Marc Fusaro, economist at Arkansas Tech University,

- Todd Zywicki, law professor at George Mason School of Law (now renamed Antonin Scalia Law School), and

- Victor Stango, professor of management at University of California, Davis.

Not all the above are necessarily guilty of truly terrible stuff; FOIA requests are still pending on some of them.

But some FOIA requests have come through. In particular, email chains that show Fusaro let a lawyer from CCRF write whole paragraphs of pro-payday lending propaganda that made it verbatim into his paper, decrying the phrase “cycle of debt” as meaningless. This is in spite of Fusaro’s claim in this same paper that CCRF had held no editorial control. And it looks like CCRF funneled about $24,000 to Fusaro for his trouble, maybe more.

Also, Fusaro had a co-author on the paper who managed to talk to the Consumer Affairs Committee in Pennsylvania’s House of Representatives about the “academic research” she had done with an economics professor, which showed great things about payday lending. And since most Payday Lending regulation happens at the state level – although the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is considering rules to create national standards – the statehouse is the end-goal for such lobbyists.

Professor Priestley also got funding for a pro-payday lending paper, and in spite of the fact that various FOIA requests are being legally blocked, one of her footnotes is exactly the same wording as we saw above:

There’s more, look at the article.

I’m so glad Freakonomics is doing this kind of investigative reporting. The CFPB has enough work on its hands without so-called impartial research being compromised left and right.