Book Release! and more

Oh my god, people, today’s the day! I’m practically bursting with excitement and anxiety. I feel like throwing up all the time, but in a good way. I want to go into every bookstore I walk by, find my book, and throw up all over it. That would be so nice, right?

Also, I wanted to mention that Carrie Fisher, who is a SUPREME ROLE MODEL TO ME, has just started an advice column at the Guardian. How exciting is that?! So please, anyone who still mourns the loss of Aunt Pythia, go ahead and take a look, she’s just the best.

Also! I’m into this new report, and accompanying Medium piece, by Team Upturn on the subject of predictive policing. It explains the field in a comprehensive way, and offers a convincing critique as well.

Also! It turns out I’ll be in Berkeley next Friday, here’s the flier thanks to Professor Marion Fourcade:

I hope I see you there!

Tech industry self-regulates AI ethics in secret meetings

This morning I stumbled upon a New York Times article entitled How Tech Giants Are Devising Real Ethics for Artificial Intelligence. The basic idea, and my enormously enraged reaction to that idea, is perfectly captured in this one line:

… the basic intention is clear: to ensure that A.I. research is focused on benefiting people, not hurting them, according to four people involved in the creation of the industry partnership who are not authorized to speak about it publicly.

So we have no window into understanding how insiders – unnamed, but coming from enormously powerful platforms like Google, Amazon, Facebook, IBM, and Microsoft – think about benefit versus harm, about who gets harmed and how you measure that, and so on.

That’s not good enough. This should be an open, public discussion.

Citi Bike comes to Columbia

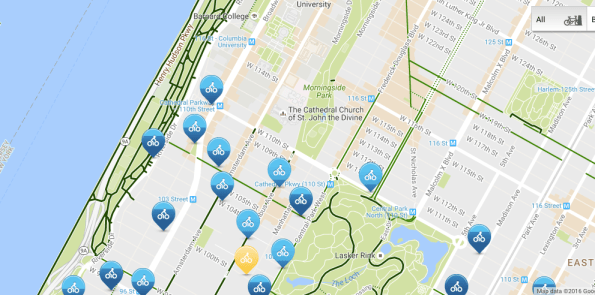

I’m unreasonably excited that Citi Bike has finally expanded to the area where I live, Columbia University. Here’s the situation:

Specifically, this means I can drop my kid off at school at 110th and Broadway and then bike downtown.

People, this is huge. It means I never have to get on the 1 train at rush hour again! Unless everyone else has the same plan as me, of course.

Excerpt of my book in the Guardian!

Wow, people, an excerpt of my book has been published in the Guardian this morning. How exciting is this? I hope you like it, it’s got a fancy graphic:

This is the result of my amazing Random House UK publicity team, who have been busy promoting my book in the UK.

That same team is bringing me to London at the end of September for a book tour, and as part of that I’m excited to announce I’ll be at the How To: Academy on September 27th, talking about my book, which was Tickets are available here.

Also, if you haven’t gotten enough of Weapons of Math Destruction this morning, take a look at Evelyn Lamb’s review in Scientific American.

Update: the print edition of the Guardian also looks smashing:

In Time Magazine!

The amazing and talented Rana Foroohar, whom I spoke with on Slate Money not so long ago about her fascinating book, Makers and Takers: the Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business, has written a fantastic piece about my upcoming book for Time Magazine.

The link is here. Take a look, it’s a great piece.

Also, I was profiled as a math nerd last week by a Bloomberg journalist.

BISG Methodology

I’ve been tooling around with the slightly infamous BISG methodology lately. It’s a simple concept which takes the last name of a person, as well as the zip code of their residence, and imputes the probabilities of that person being of various races and ethnicities using the Bayes updating rule.

The methodology is implemented with the most recent U.S. census data and critically relies on the fact that segregation is widespread in this country, especially among whites and blacks, and that Asian and Hispanic last names are relatively well-defined. It’s not a perfect methodology, of course, and it breaks down in the cases that people marry people of other races, or there are names in common between races, and especially when they live in diverse neighborhoods.

The BISG methodology came up recently in this article (hat tip Don Goldberg) about the man who invented it and the politics surrounding it. Specifically, it was recently used by the CFPB to infer disparate impact in auto lending, and the Republicans who side with auto lending lobbyists called it “junk science.” I blogged about this here and, even earlier, here.

Their complaints, I believe, center around the fact that the methodology, being based on the entire U.S. population, isn’t entirely accurate when it comes to auto lending, or for that matter when it comes to mortgages, which was the CFPB’s “ground truth” testing arena.

And that’s because minorities basically have less wealth, due to a bunch of historical racist reasons, but the upshot is that this methodology assumes a random sampling of the U.S. population but what we actually see in auto financing isn’t random.

Which begs the question, why don’t we update the probabilities with the known distribution of auto lending? That’s the thing about Bayes Law, we can absolutely do that. And once we did that, the Republican’s complaint would disappear. Please, someone tell me what I’m misunderstanding.

Between you and me, I think the real gripe is something along the lines of the so-called voter fraud problem, which is not really a problem statistically but since examples can be found of mistakes, we might imagine they’re widespread. In this case, the “mistake” is a white person being offered restitution for racist auto lending practices, which happens, and is a strange problem to have, but needs to be compared to not offering restitution to a lot of people who actually deserve it.

Anyhoo, I’m planning to add the below code to github, but I recently purchased a new laptop and I haven’t added a public key yet, so I’ll get to it soon. To be clear, the below code isn’t perfect, and it only uses zip code whereas a more precise implementation would use addresses. I’m supplying this because I didn’t find it online in python, only in STATA or something crazy expensive like that. Even so, I stole their munged census data, which you can too, from this github page.

Also, I can’t seem to get the python spacing to work in WordPress, so this is really pretty terrible, but python users will be able to figure it out until I can get it on github.

%matplotlib inline

import numpy

import matplotlib

from pandas import *

import pylab

pylab.rcParams[‘figure.figsize’] = 16, 12

#Clean your last names and zip codes.

def get_last_name(fullname):

parts_list = fullname.split(‘ ‘)

while parts_list[-1] in [”, ‘ ‘,’ ‘,’Jr’, ‘III’, ‘II’, ‘Sr’]:

parts_list = parts_list[:-1]

if len(parts_list)==0:

return “”

else:

return parts_list[-1].upper().replace(“‘”, “”)

def clean_zip(fullzip):

if len(str(fullzip))<5:

return 0

else:

try:

return int(str(fullzip)[:5])

except:

return 0

Test = read_csv(“file.csv”)

Test[‘Name’] = Test[‘name’].map(lambda x: get_last_name(x))

Test[‘Zip’] = Test[‘zip’].map(lambda x: clean_zip(x))

#Add zip code probabilities. Note these are probability of living in a specific zip code given that you have a given race. They are extremely small numbers.

F = read_stata(“zip_over18_race_dec10.dta”)

print “read in zip data”

names =[‘NH_White_alone’,’NH_Black_alone’, ‘NH_API_alone’, ‘NH_AIAN_alone’, ‘NH_Mult_Total’, \

‘Hispanic_Total’,’NH_Other_alone’]

trans = dict(zip(names, [‘White’, ‘Black’, ‘API’, ‘AIAN’, ‘Mult’, ‘Hisp’, ‘Other’]))

totals_by_race = [float(F[r].sum()) for r in names]

sum_dict = dict(zip(names, totals_by_race))

#I’ll use the generic_vector down below when I don’t have better name information

generic_vector = numpy.array(totals_by_race)/numpy.array(totals_by_race).sum()

for r in names:

F[‘pct of total %s’ %(trans[r])] = F[r]/sum_dict[r]

print “ready to add zip probabilities”

def get_zip_probs(zip):

G = F[F[‘ZCTA5’]==str(zip)][[‘pct of total White’,’pct of total Black’, ‘pct of total API’, \

‘pct of total AIAN’, ‘pct of total Mult’, ‘pct of total Hisp’, \

‘pct of total Other’]]

if len(G.values)>0:

return numpy.array(G.values[0])

else:

print “no data for zip = “, zip

return numpy.array([1.0]*7)

Test[‘Prob of zip given race’] = Test[‘Zip’].map(lambda x: get_zip_probs(x))

#Next, compute the probability of each race given a specific name.

Names = read_csv(“app_c.csv”)

print “read in name data”

def clean_probs(p):

try:

return float(p)

except:

return 0.0

for cat in [‘pctwhite’, ‘pctblack’, ‘pctapi’, ‘pctaian’, ‘pct2prace’, ‘pcthispanic’]:

Names[cat] = Names[cat].map(lambda x: clean_probs(x)/100.0)

Names[‘pctother’] = Names.apply(lambda row: max (0, 1 – float(row[‘pctwhite’]) – \

float(row[‘pctblack’]) – float(row[‘pctapi’]) – \

float(row[‘pctaian’]) – float(row[‘pct2prace’]) – \

float(row[‘pcthispanic’])), axis = 1)

print “ready to add name probabilities”

def get_name_probs(name):

G = Names[Names[‘name’]==name][[‘pctwhite’, ‘pctblack’, ‘pctapi’, ‘pctaian’, ‘pct2prace’, ‘pcthispanic’, ‘pctother’]]

if len(G.values)>0:

return numpy.array(G.values[0])

else:

return generic_vector

Test[‘Prob of race given name’] = Test[‘Name’].map(lambda x: get_name_probs(x))

#Finally, use the Bayesian updating formula to compute overall probabilities of each race.

Test[‘Prod’] = Test[‘Prob of zip given race’]*Test[‘Prob of race given name’]

Test[‘Dot’] = Test[‘Prod’].map(lambda x: x.sum())

Test[‘Final Probs’] = Test[‘Prod’]/Test[‘Dot’]

Test[‘White Prob’] = Test[‘Final Probs’].map(lambda x: x[0])

Test[‘Black Prob’] = Test[‘Final Probs’].map(lambda x: x[1])

Test[‘API Prob’] = Test[‘Final Probs’].map(lambda x: x[2])

Test[‘AIAN Prob’] = Test[‘Final Probs’].map(lambda x: x[3])

Test[‘Mult Prob’] = Test[‘Final Probs’].map(lambda x: x[4])

Test[‘Hisp Prob’] = Test[‘Final Probs’].map(lambda x: x[5])

Test[‘Other Prob’] = Test[‘Final Probs’].map(lambda x: x[6])

Book Tour Events!

Readers, I’m so happy to announce upcoming public events for my book tour, which starts in 2 weeks! Holy crap!

The details aren’t all entirely final, and there may be more events added later, but here’s what we’ve got so far. I hope I see some of you soon!

—

Events for Cathy O’Neil

Author of

WEAPONS OF MATH DESTRUCTION:

How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy

(Crown; September 6, 2016)

–

Thursday, September 8

7:00pm

Reading/Signing/Talk with Felix Salmon

Barnes & Noble Upper East Side

150 E 86th St.

New York, NY 10028

–

Tuesday, September 13

7:30pm

In Conversation Event

1119 8th Ave.

Seattle, WA 98101

–

Wednesday, September 14

12:00pm

Democracy/Citizenship Series

57 Post St.

San Francisco, CA 94104

–

Wednesday, September 14

7:00pm

In Conversation with Lianna McSwain

51 Tamal Vista Blvd.

Corte Madera, CA 94925

–

Thursday, September 15

9:00am

San Jose Marriott

301 S. Market Street

San Jose, CA 95113

–

Tuesday, September 20

6:30pm

In Conversation with Jen Golbeck

Busboys and Poets (w/Politics & Prose)

1025 5th Street NW

Washington, D.C. 20001

–

Monday, October 3

7:00pm

Reading/Signing

1256 Mass Ave.

Cambridge, MA 02138

–

Saturday, October 22nd

12:00pm

Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery

–

For more information or to schedule an interview contact:

Sarah Breivogel, 212-572-2722, sbreivogel@penguinrandomhouse.com or

Liz Esman, 212-572-6049, lesman@penguinrandomhouse.com

Chicago’s “Heat List” predicts arrests, doesn’t protect people or deter crime

A few months ago I publicly pined for a more scientific audit of the Chicago Police Department’s “Heat List” system. The excerpt from that blogpost:

…the Chicago Police Department uses data mining techniques of social media to determine who is in gangs. Then they arrest scores of people on their lists, and finally they tout the accuracy of their list in part because of the percentage of people who were arrested who were also on their list. I’d like to see a slightly more scientific audit of this system.

Thankfully, my request has officially been fulfilled!

Yesterday I discovered via Marcos Carreiro on Twitter, that a paper has been written entitled Predictions put into practice: a quasi-experimental evaluation of Chicago’s predictive policing pilot, written by

The paper’s main result upheld my suspicions:

Individuals on the SSL are not more or less likely to become a victim of a homicide or shooting than the comparison group, and this is further supported by city-level analysis. The treated group is more likely to be arrested for a shooting.

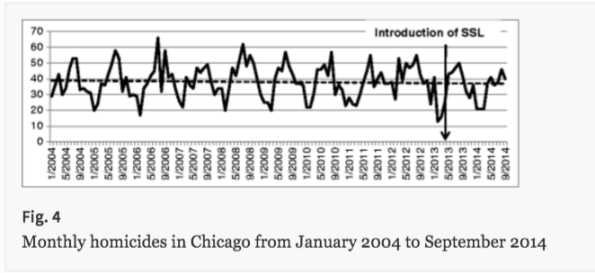

Inside the paper, they make the following important observations. First, crime rates have been going down over time, and the “Heat List” system has not effected that trend. An excerpt:

…the statistically significant reduction in monthly homicides predated the introduction of the SSL, and that the SSL did not cause further reduction in the average number of monthly homicides above and beyond the pre-existing trend.

Here’s an accompanying graphic:

This is a really big and important point, one that smart people like Gillian Tett get thrown off by when discussing predictive policing tools. We cannot automatically attribute success to any policing policy in the context of meta-effects.

Next, being on the list doesn’t protect you:

However, once other demographics, criminal history variables, and social network risk have been controlled for using propensity score weighting and doubly-robust regression modeling, being on the SSL did not significantly reduce the likelihood of being a murder or shooting victim, or being arrested for murder.

But it does make it more likely for you to get surveilled by police:

Seventy-seven percent of the SSL subjects had at least one contact card over the year following the intervention, with a mean of 8.6 contact cards, and 60 % were arrested at some point, with a mean of 1.53 arrests. In fact, almost 90 % had some sort of interaction with the Chicago PD (mean = 10.72 interactions) during the year-long observation window. This increased surveillance does appear to be caused by being placed on the SSL. Individuals on SSL were 50 % more likely to have at least one contact card and 39 % more likely to have any interaction (including arrests, contact cards, victimizations, court appearances, etc.) with the Chicago PD than their matched comparisons in the year following the intervention. There was no statistically significant difference in their probability of being arrested or incapacitated8 (see Table 4). One possibility for this result, however, is that, given the emphasis by commanders to make contact with this group, these differences are due to increased reporting of contact cards for SSL subjects.

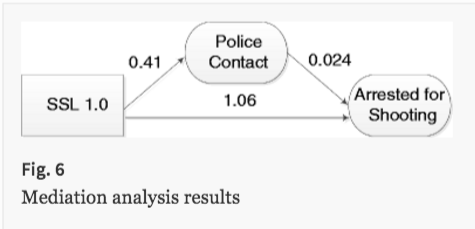

And, most importantly, being on the list means you are likely to be arrested for shooting, but it doesn’t cause that to be true:

In other words, the additional contact with police did not result in an increased likelihood for arrests for shooting, that is, the list was not a catalyst for arresting people for shootings. Rather, individuals on the list were people more likely to be arrested for a shooting regardless of the increased contact.

That also comes with an accompanying graphic:

From now on, I’ll refer to Chicago’s “Heat List” as a way for the police to predict their own future harassment and arrest practices.

What is alpha?

Last week on Slate Money I had a disagreement, or at least a lively discussion, with Felix Salmon and Josh Barro on the definition of alpha.

They said it was anything that a portfolio returned above and beyond the market return, given the amount of risk the portfolio was carrying. That’s not different from how wikipedia defines alpha, and I’ve seen it said in more or less this way in a lot of places. Thus the confusion.

However, while working as a quant at a hedge fund, I was taught that alpha was the return of a portfolio that was uncorrelated to the market.

It’s a confusing thing to discuss, partly because the concept of “risk” is somewhat self-referential – more on that soon – and partly because we sometimes embed what’s called the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) into our assumptions when we talk about how portfolio returns work.

Let’s start with the following regression, which refers to stock-based portfolios, and which defines alpha:

Now, the term term refers to the risk-free rate, or in other words how much interest you get on US treasuries, which we can approximate by 0 because it’s easier to ignore them and because it’s actually pretty close to 0 anyway. That cleans up our formula:

In this regression, we are fitting the coefficients and

to many instances of time windows where we’ve measured our portfolio’s return

and the market’s return

Think of market as the S&P500 index, and think of the time windows as days.

So first, defining alpha with the above regression does what I claimed it would do: it “picks off” that part of the portfolio returns that are correlated to the market and put it in the beta coefficient, and the rest is left to alpha. If beta is 1, alpha is 0, and if the error terms are all zero, you are following the market exactly.

On the other hand, the above formulation also seems to support Felix’s suggestion that alpha is the return that is not accounted for by risk. The thing is, it’s true, at least according to the CAPM theory of investing, which says you can’t do better than the market, that you’re rewarded by market your risk in a direct way, and that everyone knows this and refuses to take on other, unrewarded risks. In particular, alpha in the above equation should be zero, but anything “extra” that you earn beyond the expected market returns would be represented by alpha in the above regression.

So, are we actually agreeing?

Well, no. The two approaches to defining alpha are very different. In particular, my definition has no reference to CAPM. Say for a moment we don’t believe in CAPM. We can still run the regression above. All we’re doing, when we run that regression, is measuring the extent to which our portfolio’s returns are “explained” by its overlap with the market.

In particular, we do not expect the true risk of our portfolio to be apparent in the above equation. Which brings us to how risk is defined, and it’s weird, because it cannot be directly measured. Instead, we typically infer risk from the volatility – computed as standard deviation – of past returns.

This isn’t a terrible idea, because if something moves around wildly on a daily basis, it would appear to be pretty risky. But it’s also not the greatest idea, as we learned in 2008, because lots of credit instruments like credit default swaps move very little on a daily basis but then suddenly lose tremendous value overnight. So past performance is not always indicative of future performance.

But it’s what we’ve got, so let’s hold on to it for the discussion. The key observation is the following:

The above regression formula only displays the market-correlated risk, and the remaining risk is unmeasured. A given portfolio might have incredibly wild swings in value, but as long as they are uncorrelated to the market, they will be invisible to the above equation, showing up only in the error terms.

Said another way, alpha is not truly risk-adjusted. It’s only market-risk-adjusted.

We might have an investment portfolio with a large alpha and a small beta, and someone who only follows CAPM theory would tell me we’re amazing investors. In fact hedge funds try to minimize their relationship to market returns – that’s the “hedge” in hedge funds – and so they’d want exactly that, a large alpha, a tiny beta, and quite a bit of risk. [One caveat: some people stipulate that a lot of that uncorrelated return is fabricated through sleazy accounting.]

It’s not like I am alone here – for a long time people have been aware that there’s lots of risk that’s not represented by market risk – for example, other instrument classes and such. So instead of using a simplistic regression like the one above, people generalize everything in sight and use the Sharpe ratio, which is the ratio of returns (often relative to some benchmark or index) to risks, where risks are measured by more complicated volatility-like computations.

However, that more general concept is also imperfect, mostly because it’s complicated and highly gameable. Portfolio managers are constantly underestimating the risk they take on, partly because – or entirely because – they can then claim to have a high Sharpe ratio.

How much does this matter? People have a colloquial use for the word alpha that’s different from my understanding, which isn’t surprising. The problem lies in the possibility that people are bragging when they shouldn’t, especially when they’re hiding risk, and especially especially if your money is on the line.

The truth about clean swimming pools

There’s been a lot of complaints about the Olympic pools turning green and dirty in Rio. People seem worried that the swimmers’ health may be at risk and so on.

Well, here’s what I learned last month when my family rented a summer house with a pool. Pools that look clean are not clean. They would be better described as, “so toxic that algae cannot live in it.”

I know what I’m talking about. One weekend my band visiting the house, and the pool guy had been missing for 2 weeks straight. This is what my pool looks like:

Album cover, obviously.

Then we added an enormous vat of chemicals, specifically liquid chlorine, and about 24 hours later this is what happened:

It wasn’t easy to recreate this. I had to throw the shark’s tail at Jamie like 5 times because it kept floating away. Also, back of the album, obviously.

Now you might notice that it’s not green anymore, but it’s also not clear. To get to clear, blue water, you need to add yet another tub of some other chemical.

Long story short: don’t be deceived by “clean” pool water. There’s nothing clean about it.

Update: I’m not saying “chemicals are bad,” and please don’t compare me to the – ugh – Food Babe! I’m just saying “clean water” isn’t an appropriate description. It’s not as if it’s pure water, and we pour tons of stuff in to get it to look like that. So yes, algae and germs can be harmful! And yes, chlorine in moderate amounts is not bad for you!

Donald Trump is like a biased machine learning algorithm

Bear with me while I explain.

A quick observation: Donald Trump is not like normal people. In particular, he doesn’t have any principles to speak of, that might guide him. No moral compass.

That doesn’t mean he doesn’t have a method. He does, but it’s local rather than global.

Instead of following some hidden but stable agenda, I would suggest Trump’s goal is simply to “not be boring” at Trump rallies. He wants to entertain, and to be the focus of attention at all times. He’s said as much, and it’s consistent with what we know about him. A born salesman.

What that translates to is a constant iterative process whereby he experiments with pushing the conversation this way or that, and he sees how the crowd responds. If they like it, he goes there. If they don’t respond, he never goes there again, because he doesn’t want to be boring. If they respond by getting agitated, that’s a lot better than being bored. That’s how he learns.

A few consequences. First, he’s got biased training data, because the people at his rallies are a particular type of weirdo. That’s one reason he consistently ends up saying things that totally fly within his training set – people at rallies – but rub the rest of the world the wrong way.

Next, because he doesn’t have any actual beliefs, his policy ideas are by construction vague. When he’s forced to say more, he makes them benefit himself, naturally, because he’s also selfish. He’s also entirely willing to switch sides on an issue if the crowd at his rallies seem to enjoy that.

In that sense he’s perfectly objective, as in morally neutral. He just follows the numbers. He could be replaced by a robot that acts on a machine learning algorithm with a bad definition of success – or in his case, a penalty for boringness – and with extremely biased data.

The reason I bring this up: first of all, it’s a great way of understanding how machine learning algorithms can give us stuff we absolutely don’t want, even though they fundamentally lack prior agendas. Happens all the time, in ways similar to the Donald.

Second, some people actually think there will soon be algorithms that control us, operating “through sound decisions of pure rationality” and that we will no longer have use for politicians at all.

And look, I can understand why people are sick of politicians, and would love them to be replaced with rational decision-making robots. But that scenario means one of three things:

- Controlling robots simply get trained by the people’s will and do whatever people want at the moment. Maybe that looks like people voting with their phones or via the chips in their heads. This is akin to direct democracy, and the problems are varied – I was in Occupy after all – but in particular mean that people are constantly weighing in on things they don’t actually understand. That leaves them vulnerable to misinformation and propaganda.

- Controlling robots ignore people’s will and just follow their inner agendas. Then the question becomes, who sets that agenda? And how does it change as the world and as culture changes? Imagine if we were controlled by someone from 1000 years ago with the social mores from that time. Someone’s gonna be in charge of “fixing” things.

- Finally, it’s possible that the controlling robot would act within a political framework to be somewhat but not completely influenced by a democratic process. Something like our current president. But then getting a robot in charge would be a lot like voting for a president. Some people would agree with it, some wouldn’t. Maybe every four years we’d have another vote, and the candidates would be both people and robots, and sometimes a robot would win, sometimes a person. I’m not saying it’s impossible, but it’s not utopian. There’s no such thing as pure rationality in politics, it’s much more about picking sides and appealing to some people’s desires while ignoring others.

Holy crap – an actual book!

Yo, everyone! The final version of my book now exists, and I have exactly one copy! Here’s my editor, Amanda Cook, holding it yesterday when we met for beers:

Here’s my son holding it:

He’s offered to become a meme in support of book sales.

Here’s the back of the book, with blurbs from really exceptional people:

In other exciting book news, there’s a review by Richard Beales from Reuter’s BreakingViews, and it made a list of new releases in Scientific American as well.

Endnote:

I want to apologize in advance for all the book news I’m going to be blogging, tweeting, and otherwise blabbing about. To be clear, I’ve been told it’s my job for the next few months to be a PR person for my book, so I guess that’s what I’m up to. If you come here for ideas and are turned off by cheerleading, feel free to temporarily hate me, and even unsubscribe to whatever feed I’m in for you!

But please buy my book first, available for pre-order now. And feel free to leave an amazing review.

Who Counts as a Futurist? Whose Future Counts?

This is a guest post by Matilde Marcolli, a mathematician and theoretical physicist, who also works on information theory and computational linguistics. She studied theoretical physics in Italy and mathematics at the University of Chicago. She worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics, and is currently a professor at Caltech. This post in in response to Cathy’s last post.

History of Futurism

For a good part of the past century the term “futurism” conjured up the image of a revolutionary artistic and cultural movement that flourished in Russia and Italy in the first two decades of the century. In more recent times and across the Atlantic, it has acquired a different connotation, one related to speculative thought about the future of advanced technology. In this later form, it is often explicitly associated to the speculations of a group of Silicon Valley tycoons and their acolytes.

Their musings revolve around a number of themes: technological immortality in the form of digital uploading of human consciousness, space colonization, and the threat of an emergent superintelligent AI. It is easy to laugh off all these ideas as the typical preoccupations of a group of aging narcissist wealthy white males, whose greatest fear is that an artificial intelligence may one day treat them the way they have been treating everybody else all along.

However, in fact none of these themes of “futurist speculation” originates in Silicon Valley: all of them have been closely intertwined in history and date back to the original Russian Futurism, and the related Cosmist movement, where mystics like Fedorov alternated with scientists like Tsiolkovsky (the godfather of the Soviet space program) envisioning a future where science and technology would “storm the heavens and vanquish death”.

The crucial difference in these forms of futurism does not lie in the themes of speculation, but rather in the role of humanity in this envisioned future. Is this the future of a wealthy elite? Is this the future of a classless society?

Strains of Modern Futurism

Fast forward to our time again, there are still widely different versions of “futurism” and not all of them are a capitalist protectorate. Indeed, there is a whole widely developed Anarchist Futurism (usually referred to as Anarcho-Transhumanism) which is anti-capitalist but very pro-science and technology. It has its roots in many historical predecessors: the Russian Futurism and Cosmism, naturally, but also the revolutionary brand of the Cybernetic movement (Stafford Beer, etc.), cultural and artistic movements like Afrofuturism and Solarpunk, Cyberfeminism (starting with Donna Haraway’s Cyborg), and more recently Xenofeminism.

What some of the main themes of futurism look like in the anarchist lamelight is quite different from their capitalist shadow.

Fighting Prejudice with Technology

“Morphological Freedom” is one of the main themes of anarchist transhumanism: it means the freedom to modify one’s own body with science and technology, but whereas in the capitalist version of transhumanism this gets immediately associated to Hollywood-style enhanced botox therapies for those incapable of coming to terms with their natural aging process, in the anarchist version the primary model of morphological freedom is the transgender rights, the freedom to modify one’s own sexual and gender identity.

It also involves a fight against ableism, in as there is nothing especially ideal about the (young, muscular, male, white, healthy) human body.

The Vitruvian Man, which was the very symbol of Humanism, was also a symbol of the intrinsically exclusionary nature of Humanism. Posthumanism and Transhumanism are also primarily an inclusionary process that explodes the exclusionary walls of Humanism, without negating its important values (for example Humanism replaced religious thinking by a basis for ethical values grounded in human rights).

An example of Morphological Freedom against ableism is the rethinking of the notion of prosthetics. The traditional approach aimed at constructing artificial limbs that as much as possible resemble the human limbs, implicitly declaring the user of prosthetics in some way “defective”.

However, professional designers have long realized that prosthetic arms that do not imitate a human arm, but that work like an octopus tentacle can be more efficient than most traditional prosthetics. And when children are given the possibility to design and 3D print their own prosthetics, they make colorful arms that launch darts and flying saucers and that make them look like superheroes. Anarchist transhumanism defends the value and importance of neurodiversity.

Protesting with Technology

The mathematical theory of networks and of complex systems and emergent behavior can be used to make protests and social movements more efficient and successful. Sousveillance and anti-surveillance techniques can help protecting people from police brutality. Hacker and biohacker spaces help spreading scientific literacy and directly involve people in advanced science and technology: the growing community of DIY synthetic biology with biohacker spaces like CounterCulture Labs, has been one of the most successful grassroot initiatives involving advanced science. These are all important aspects and components of the anarchist transhumanist movement.

Needless to say, the community of people involved in Anarcho-Tranhumanism is a lot more diverse than the typical community of Silicon Valley futurists. Anarchism itself comes in many different forms, anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndacalism, mutualism, etc. (no, not anarcho-capitalism, that is an oxymoron not a political movement!) but at heart it is an ethical philosophy aimed at increasing people’s agency (and more generally the agency of any sentient being), based on empathy, cooperation, mutual aid.

Conclusion

Science and technology have enormous potential, if used inclusively and for the benefit of all and not with goals of profit and exploitation.

For people interested in finding out more about Anarcho-Tranhumanism there is an Anarcho-Transhumanist Manifesto currently being written (which is still very much in the making): the parts that are written at this point can be accessed here.

There is also a dedicated Facebook page, which posts on a range of topics including anarchist theory, philosophy, transhumanism and posthumanism and their historical roots, and various thoughts on science and technology and their transformative role.

The opinions expressed by the author are solely her own: her past and current affiliations are listed for identification purposes only.

The Absurd Moral Authority of Futurism

Yesterday one of my long-standing fears was confirmed: futurists are considered moral authorities.

The Intercept published an article entitled Microsoft Pitches Technology That Can Read Facial Expressions at Political Rallies, and written by Alex Emmons, which described a new Microsoft product that is meant to be used at large events like the Superbowl, or a Trump rally, to discern “anger, contempt, fear, disgust, happiness, neutral, sadness or surprise” in the crowd.

Spokesperson Kathryn Stack, when asked whether the tool could be used to identify dissidents or protesters, responded as follows:

“I think that would be a question for a futurist, not a technologist.”

Can we parse that a bit?

First and foremost, it is meant to convey that the technologists themselves are not responsible for the use of their technologies, even if they’ve intentionally designed it for sale to political campaigns.

So yeah, I created this efficient plug-and-play tool of social control, but that doesn’t mean I expect people to use it!

Second, beyond the deflecting of responsibility, the goal of that answer is to point to the person who really is in charge, which is for some reason “a futurist.” What?

Now, my experience with futurists is rather limited – although last year I declared myself to be one – but even so, I’d like to point out that futurism is male dominated, almost entirely white, and almost entirely consists of Silicon Valley nerds. They spend their time arguing about the exact timing and nature of the singularity, whether we’ll live forever in bliss or we’ll live forever under the control of rampant and hostile AI.

In particular, there’s no reason to imagine that they are well-versed in the history or in the rights of protesters or of political struggle.

In Star Wars terms, the futurists are the Empire, and Black Lives Matter are the scrappy Rebel Alliance. It’s pretty clear, to me at least, that we wouldn’t go to Emperor Palpatine for advice on ethics.

Expand Social Security, get rid of 401Ks

People, can we face some hard truths about how Americans save for retirement?

It Isn’t Happening

Here’s a fact: most people aren’t seriously saving for retirement. Ever since we chucked widespread employer based pension systems for 401K’s and personal responsibility, people just haven’t done very well saving. They take money out for college for their kids, or an unforeseen medical expense, or they just never put money in in the first place. Very few people are saving adequately.

In Fact, It Shouldn’t Happen

Next: it’s actually, mathematically speaking, extremely dumb to have 401K’s instead of a larger pool of retirement money like pensions or Social Security.

Why do I say that? Simple. Imagine everyone was doing a great job saving for retirement. This would mean that everyone “had enough” for the best-case scenario, which is to say living to 105 and dying an expensive, long-winded death. That’s a shit ton of money they’d need to be saving.

But most people, statistically speaking, won’t live until 105, and their end-of-life care costs might not always be extremely high. So for everyone to prepare for the worst is total overkill. Extremely inefficient to the point of hoarding, in fact.

Pooled Retirement Systems Are Key

Instead, we should think about how much more efficient it is to pool retirement savings. Then lots of people die young and are relatively “cheap” for the pool, and some people live really long but since it’s all pooled, things even out. It’s a better and more efficient system.

Most pension plans work like this, but they’ve fallen out of favor politically. And although some people complain that it’s hard to reasonably fund pension funds, most of that is actually poorly understood. Even so, I don’t see employer-based pension plans making a comeback.

Social Security is actually the best system we have, and given how few people have planned and saved for retirement, we should invest heavily in it, since it’s not sufficient to keep elderly people above the poverty line. And, contrary to popular opinion, Social Security isn’t going broke, could easily be made whole and then some, and is the right thing to do – both morally and mathematically – for our nation.

Stuff’s going on! Some of it’s progress!

Stuff’s going on, peoples, and some of it’s actually really great. I am so happy to tell you about it now that I’m back from vacation.

- The Tampon Tax is gone from New York State. This is actually old news but I somehow forgot to blog it. As my friend Josh says, we have to remember to celebrate our victories!!

- Next stop, Menstrual Equality! Jennifer Weiss-Wolf is a force of nature and she won’t stop until everyone has a free tampon in their… near vicinity.

- There’s a new “bail” algorithm in San Francisco, built by the Arnold Foundation. The good news is, they aren’t using educational background and other race and class proxies in the algorithm. The bad news is, they’re marketing it just like all the other problematic WMD algorithms out there. According to Arnold Foundation vice president of criminal justice Matt Alsdorf, “The idea is to provide judges with objective, data-driven, consistent information that can inform the decisions they make.” I believe the consistent part, but I’d like to see some data about the claim of objectivity. At the very least, Arnold Foundation, can you promise a transparent auditing process of your bail algorithms?

- In very very related news, Julia Angwin calls for algorithmic accountability.

- There’s a new method to de-bias sexist word corpora using vector algebra and Mechanical Turks. Cool! I might try to understand the math here and tell you more about it at a later date.

- Speaking of Mechanical Turk, are we paying them enough? The answer is no. Let’s require a reasonable hourly minimum wage for academic work. NSF?

Reform the CFAA

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act is badly in need of reform. It currently criminalizes violations of terms of services for websites, even when those terms of service are written in a narrow way and the violation is being done for the public good.

Specifically, the CFAA keeps researchers from understanding how algorithms work. As an example, Julia Angwin’s recent work on recidivism modeling, which I blogged about here, was likely a violation of the CFAA:

A more general case has been made for CFAA reform in this 2014 paper, Auditing Algorithms: Research Methods for Detecting Discrimination on Internet Platforms, written by Christian Sandvig, Kevin Hamilton, Karrie Karahalios, and Cedric Langbort.

They make the case that discrimination audits – wherein you send a bunch of black people and then white people to, say, try to rent an apartment from Donald Trump’s real estate company in 1972 – have clearly violated standard ethical guidelines (by wasting people’s time and not letting them in on the fact that they’re involved in a study), but since they represent a clear public good, such guidelines should have have been set aside.

Similarly, we are technically treating employers unethically when we have fake (but similar) resumes from whites and blacks sent to them to see who gets an interview, but the point we’ve set out to prove is important enough to warrant such behavior.

Their argument for CFAA reform is a direct expansion of the aforementioned examples:

Indeed, the movement of unjust face-to-face discrimination into computer algorithms appears to have the net effect of protecting the wicked. As we have pointed out, algorithmic discrimination may be much more opaque and hard to detect than earlier forms of discrimination, while at the same time one important mode of monitoring—the audit study—has been circumscribed. Employing the “traditional” design of an audit study but doing so via computer would now waste far fewer resources in order to find discrimination. In fact, it is difficult to imagine that a major internet platform would even register a large amount of auditing by researchers. Although the impact of this auditing might now be undetectable, the CFAA treats computer processor time as and a provider’s “authorization” as far more precious than the minutes researchers have stolen from honest landlords and employers over the last few decades. This appears to be fundamentally misguided.

As a consequence, we advocate for a reconceptualization of accountability on Internet platforms. Rather than regulating for transparency or misbehavior, we find this situation argues for “regulation toward auditability.” In our terms, this means both minor, practical suggestions as well as larger shifts in thinking. For example, it implies the reform of the CFAA to allow for auditing exceptions that are in the public interest. It implies revised scholarly association guidelines that subject corporate rules like the terms of service to the same cost-benefit analysis that the Belmont Report requires for the conduct of ethical research—this would acknowledge that there may be many instances where ethical researchers should disobey a platform provider’s stated wishes.

Horrifying New Credit Scoring in China

When it comes to alternative credit scoring systems, look for the phrase “we give consumers more access to credit!”

That’s code for a longer phrase: “we’re doing anything at all we want, with personal information, possibly discriminatory and destructive, but there are a few people who will benefit from this new system versus the old, so we’re ignoring costs and only counting the benefits for those people, in an attempt to distract any critics.”

Unfortunately, the propaganda works a lot of the time, especially because tech reporters aren’t sufficiently skeptical (and haven’t read my upcoming book).

—

The alt credit scoring field has recently been joined by another player, and it’s the stuff of my nightmares. Specifically, ZestFinance is joining forces with Baidu in China to assign credit scores to Chinese citizens based on the history of their browsing results, as reported in the LA Times.

The players:

- ZestFinance is the American company, led by ex-Googler Douglas Merrill who likes to say “all data is credit data” and claims he cannot figure out why people who spell, capitalize, and punctuate correctly are somehow better credit risks. Between you and me, I think he’s lying. I think he just doesn’t like to say he happily discriminates against poor people who have gone to bad schools.

- Baidu is the Google of China. So they have a shit ton of browsing history on people. Things like, “symptoms for Hepatitis” or “how do I get a job.” In other words, the company collects information on a person’s most vulnerable hopes and fears.

Now put these two together, which they already did thankyouverymuch, and you’ve got a toxic cocktail of personal information, on the one hand, and absolutely no hesitation in using information against people, on the other.

In the U.S. we have some pretty good anti-discrimination laws governing credit scores – albeit incomplete, especially in the age of big data. In China, as far as I know, there are no such rules. Anything goes.

So, for example, someone who recently googled for how to treat an illness might not get that loan, even if they were simply trying to help their friend or family member. Moreover, they will never know why they didn’t get the loan, nor will they be able to appeal the decision. Just as an example.

Am I being too suspicious? Maybe: at the end of the article announcing this new collaboration, after all, Douglas Merrill from ZestFinance is quoted touting the benefits:

“Today, three out of four Chinese citizens can’t get fair and transparent credit,” he said. “For a small amount of very carefully handled loss of privacy, to get more easily available credit, I think that’s going to be an easy choice.”

Auditing Algorithms

Big news!

I’ve started a company called ORCAA, which stands for O’Neil Risk Consulting and Algorithmic Auditing and is pronounced “orcaaaaaa”. ORCAA will audit algorithms and conduct risk assessments for algorithms, first as a consulting entity and eventually, if all goes well, as a more formal auditing firm, with open methodologies and toolkits.

So far all I’ve got is a webpage and a legal filing (as an S-Corp), but no clients.

No worries! I’m busy learning everything I can about the field, small though it is. Today, for example, my friend Suresh Naidu suggested I read this fascinating study, referred to by those in the know as “Oaxaca’s decomposition,” which separates differences of health outcomes for two groups – referred to as “the poor” and the “nonpoor” in the paper – into two parts: first, the effect of “worse attributes” for the poor, and second, the effect of “worse coefficients.” There’s also a worked-out example of children’s health in Viet Nam which is interesting.

The specific formulas they use depends crucially on the fact that the underlying model is a linear regression, but the idea doesn’t: in practice, we care about both issues. For example, with credit scores, it’s obvious we’d care about the coefficients – the coefficients are the ingredients in the recipe that takes the input and gives the output, so if they fundamentally discriminate against blacks, for example, that would be bad (but it has to be carefully defined!). At the same time, though, we also care about which inputs we choose in the first place, which is why there are laws about not being able to use race or gender in credit scoring.

And, importantly, this analysis won’t necessarily tell us what to do about the differences we pick up. Indeed many of the tests I’ve been learning about and studying have that same limitation: we can detect problems but we don’t learn how to address them.

If you have any suggestions for me on methods for either auditing algorithms or for how to modify problematic algorithms, I’d be very grateful if you’d share them with me.

Also, if there are any artists out there, I’m on the market for a logo.

Race and Police Shootings: Why Data Sampling Matters

This is a guest post by Brian D’Alessandro, who daylights as the Head of Data Science at Zocdoc and as an Adjunct Professor with NYU’s Center for Data Science. When not thinking probabilistically, he’s drumming with the indie surf rock quarter Coastgaard.

I’d like to address the recent study by Roland Fryer Jr from Harvard University, and associated NY Times coverage, that claims to show zero racial bias in police shootings. While this paper certainly makes an honest attempt to study this very important and timely problem, it ultimately suffers from issues of data sampling and subjective data preparation. Given the media attention it is receiving, and the potential policy and public perceptual implications of this attention, we as a community of data people need to comb through this work and make sure the headlines are consistent with the underlying statistics.

First thing’s first: is there really zero bias in police shootings? The evidence for this claim is, notably, derived from data drawn from a single precinct. This is a statistical red flag and might well represent selection bias. Put simply, a police department with a culture that successfully avoids systematic racial discrimination may be more willing than others to share their data than one that doesn’t. That’s not proof of cherry-picking, but as a rule we should demand that any journalist or author citing this work should preface any statistic with “In Houston, using self-reported data,…”.

For that matter, if the underlying analytic techniques hold up under scrutiny, we should ask other cities to run the same tests on their data and see what the results are more widely. If we’re right, and Houston is rather special, we should investigate what they’re doing right.

On to the next question: do those analytic techniques hold up? The short answer is: probably not.

How The Sampling Was Done

As discussed here by economist Rajiv Sethi and here by Justin Feldman, the means by which the data instances were sampled to measure racial bias in Houston police shootings is in itself potentially very biased.

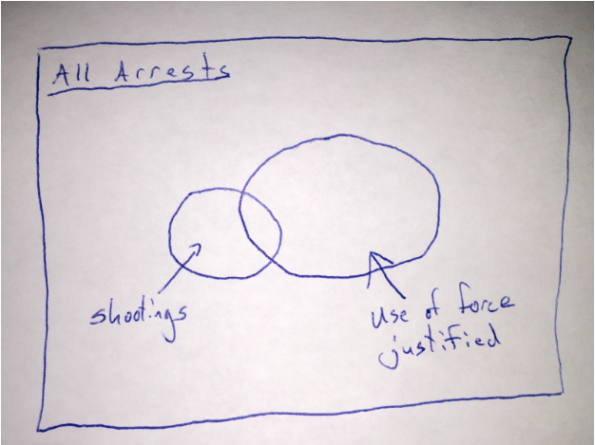

Essentially, Fryer and his team sampled “all shootings” as their set of positively labeled instances, and then randomly sampled “arrests in which use of force may have been justified” (attempted murder of an officer, resisting/impeding arrest, etc.) as the negative instances. The analysis the measured racial biases using the union of these two sets.

Here is a simple Venn diagram representing the sampling scheme:

In other words, the positive population (those with shooting) is not drawn from the same distribution as the negative population (those arrests where use of force is justified). The article implies that there is no racial bias conditional on there being an arrest where use of force was justified. However, the fact that they used shootings that were outside of this set of arrests means that this is not what they actually tested.

Instead, they only show that there was no racial bias in the set that was sampled. That’s different. And, it turns out, a biased sampling mechanism can in fact undo the bias that exists in the original data population (see below for a light mathematical explanation). This is why we take great pains in social science research to carefully design our sampling schemes. In this case, if the sampling is correlated with race (which it very likely is), all bets are off on analyzing the real racial biases in police shootings.

What Is Actually Happening

Let’s accept for now the two main claims of the paper: 1) black and hispanic people are more likely to endure some force from police, but 2) this bias doesn’t exist in an escalated situation.

Well, how could one make any claim without chaining these two events together? The idea of an escalation, or an arrest reason where force is justified, is unfortunately an often subjective concept reported after the fact. Could it be possible that a an officer is more likely to find his/her life in danger when a black, as opposed to a white, suspect reaches for his wallet? Further, while unquestioned compliance is certainly the best life-preserving policy when dealing with an officer, I can imagine that an individual being roughed up by a cop is liable to push back with an adrenalized, self-preserving an instinctual use of force. I’ll say that this is likely for black and white persons, but if the black person is more likely to be in that situation in the first place, the black person is more likely to get shot from a pre-stop position.

To sum up, the issue at hand is not whether cops are more likely to shoot at black suspects who are pointing guns straight back at the cop (which is effectively what is being reported about the study). The more important questions, which is not addressed, is why are black men more likely to pushed up against the wall by a cop in the first place, or does race matter when a cop decides his/her life is in danger and believes lethal force is necessary?

What Should Have Happened

While I empathize with the data prep challenges Fryer and team faced (the Times article mentions that put a collective 3000 person hours here), the language of the article and its ensuing coverage unfortunately does not fit the data distribution induced by the method of sampling.

I don’t want to suggest in any way that the data may have been manipulated to engineer a certain result, or that the analysis team mistakenly committed some fundamental sampling error. The paper does indeed caveat the challenge here, but given that admission, I wonder why the authors were so quick to release an un-peer-reviewed working version and push it out via the NY Times.

Peer review would likely have pointed out these issues and at least push the authors to temper their conclusions. For instance, the paper uses multiple sources to show that non-lethal violence is much more likely if you are black or hispanic, controlling for other factors. I see the causal chain being unreasonably bisected here, and this is a pretty significant conceptual error.

Overall, Fryer is fairly honest in the paper about the given data limitations. I’d love for him to take his responsibility to the next level and make his data, both in raw and encoded forms, public. Given the dependency on both subjective, manual encodings of police reports and a single, biased choice of sampling method, more sensitivity analysis should be done here. Also, anyone reporting on this (Fryer himself), should make a better effort to connect the causal chain here.

Headlines are sticky, and first impressions are hard to undo.This study needs more scrutiny at all levels, with special attention to the data preparation that has been done. We need a better impression than the one already made.

The Math

The coverage of the results comes down to the following:

P(Shooting | Black, Escalation) = P(Shooting | White, Escalation)

(here I am using ‘Escalation’ as the set of arrests where use of force is considered justified. And for notational simplicity I have omitted the control variables from the conditional above).

However, the analysis actually shows that:

P(Shooting | Black, Sampled) = P(Shooting | White, Sampled),

Where (Sampled = True) if the person was either shot or the situation escalated and the person was not shot. This makes a huge difference, because with the right bias in the sampling, we could have a situation in which there is in fact bias in police shooting but not in the sampled data. We can show this with a little application of Bayes rule:

P(Shot|B, Samp) / P(Shot|W, Samp) = [P(Shot|B) / P(Shot|W)] * [P(Samp|W) / P(Samp|B)]

The above should be read as: the bias in the study depends on both the racial bias in the population (P(S|B) / P(S|W)) and the bias in the sampling. Any bias in the population can therefore effectively be undone by a sampling scheme that is also racially biased. Unfortunately, the data summarized in the study doesn’t allow us to back into the 4 terms on the right hand side of the above equality.