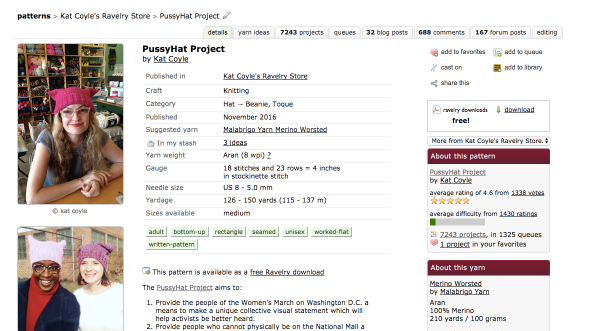

Dear President Bannon…. #PostcardsToBannon

How do you get rid of the influence of Steve Bannon’s whispering in Trump’s ear? The best strategy I’ve heard is to make Trump jealous of the attention. And one way to do that is to refer to Bannon as the president.

The hashtag #PostcardsToBannon blew up on Twitter yesterday, with all sorts of people posting pics of their postcards:

From Justin Hendrix via Twitter

In fact, it got so much attention that it was featured overnight on USA Today.

It’s a small act but it might make you feel great to do it.

Donald Trump is the Singularity

I have a new fun piece over at Bloomberg this morning:

Becky Jaffe: Resources to #Resist

This is a guest post by Becky Jaffe.

Per your request, I drafted a quick list of progressive organizations that we will want to support now more than ever. This list of national organizations is by no means comprehensive, just a good place to start if you want to get plugged in to community organizations that build power for the most marginalized sectors of our society. Each of these is a clickable link that will take you directly to the organization’s website so you can learn more about their mission. Please add to this list and circulate widely. I will be creating a Bay Area-specific list soon for people who want to support local community organizations and I encourage you to make a similar list for your region.

Let’s get busy supporting each other, people! We have our work cut out for us and much joyful organizing ahead.

Immigrant/Refugee rights:

- National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights

- National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers’ Guild

- National Immigration Law Center

- Catholic Charities

- the New American Leaders Project

- Presente

- Define American

Civil Rights, social justice and legal defense organizations:

- CAIR, the Council on American-Islamic Relations

- SURJ, Showing Up for Racial Justice

- NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- Black Lives Matter

- the Anti-Defamation League

- Race Forward

- Fred T. Korematsu Institute for Civil Rights and Education

- Bend the Arc: a Jewish partnership for Justice

- Center for Constitutional Rights

- Human Rights Watch:United States

- ACLU, the American Civil Liberties Union

- NLG, the National Lawyer’s Guild

- Legal Aid Society

- SPLC the Southern Poverty Law Center

- The Innocence Project

- Schools Not Prisons

- Anti-Eviction Mapping Project

- SEIU, Service Employees International Union

- Planned Parenthood

- National Organization for Women

LGBTQ rights:

- GLAAD: Gay And Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation

- National Center for Lesbian Rights

- Human Rights Campaign

- Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund

- Transgender Law Center

Disability rights:

Building democracy:

- Women’s March on Washington: 10 Actions for the first 100 Days

- the Equal Justice Society

- The Highlander Research and Education Center

Fight for the Future - Indivisible: Former congressional staffers reveal best practices for making Congress listen

- Common Cause

- FAIR: Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting

- Center for Digital Democracy

- Brennan Center for Justice

- Public Citizen

- Inequality Media

Environmental organizations:

Cambridge Analytica

My newest Bloomberg post is out, in response to this article about Cambridge Analytica:

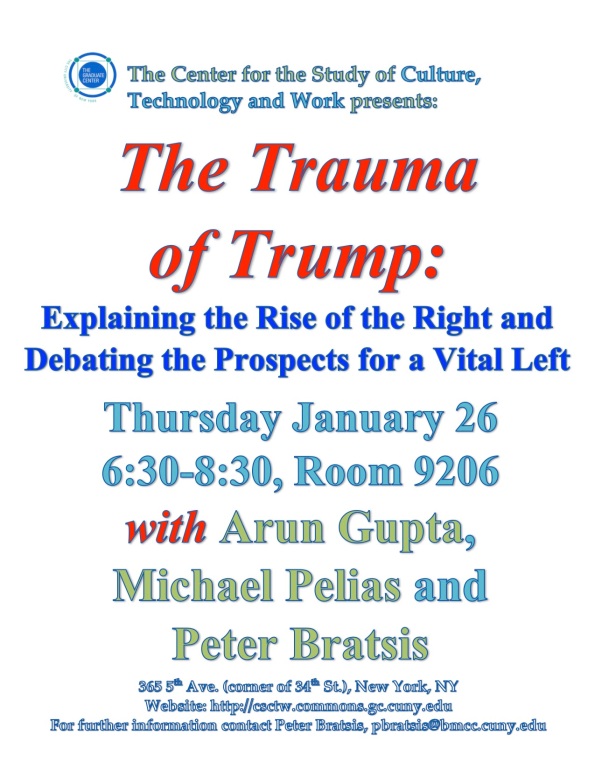

Get a New York ID Card #Resist

This is a guest post by Elizabeth Hutchinson, an Associate Professor of Art History at Barnard College/Columbia University who supports social justice initiatives at work and in her community. She is also a yarn whisperer who likes nothing better than knitting with Mathbabe.

If you are a regular reader of Mathbabe, you may already be putting your time, money and intellectual labor to work in support of organizations that defend the rights of vulnerable groups and our vulnerable environment (#BlackLivesMatter, Make the Road New York, Planned Parenthood, SURJ, 350.org, NYCStandswithStandingRock, and many others).

But if you are a New York City resident, here’s another practical thing you can do: apply for an ID NYC card.

ID NYC is a program established by the de Blasio administration in 2014 that allows city residents to obtain a photo identification without requiring the same government-generated documents required for a drivers license or passport. These residents then have a municipal ID that can help them open bank accounts, apply for library cards and gain access to other services as well as free membership to a range of NYC cultural institutions like the Museum of Modern Art.

In lieu of a Social Security card or equivalent document, applicants for the ID NYC could use non-U.S. government-generated forms of identification, including, among other things, a combination of a utility bill verifying a local address and a foreign passport or consular identification.

Even if you have a photo ID and a library card, here’s why you should get an ID NYC: this program is widely used by the undocumented immigrants in our midst, and the records of their applications are vulnerable to seizure by federal government authorities charged with expanding the pursuit of both undocumented and documented immigrants.

How is this so, you might ask, knowing that New York is a sanctuary city? Well, it is true that New York is committed to not aiding Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in a number of ways. For example, it has pledged not to use its city precincts or jails to house immigrants detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (though it does cooperate when ICE requests individuals already in NYC custody who were convicted of a serious felony) and to not share city agency information with federal immigration authorities.

Sanctuary Cities according to this site. For a more complete list click here.

The ID NYC program was set up to be in line with this stance: the law establishing the program ordered that the copies of documents used in applying for the ID be destroyed at the end of the first two years, or in December 2016, in the meantime only sharing them with law enforcement only through judicial subpoena (something that happened only a handful of times). However, a case brought by Republican members of the State Assembly from Staten Island in December resulted in a ruling that all records be retained indefinitely.

After Trump’s election, Mayor de Blasio pledged to change the record keeping system and stop retaining copies of the applicants’ documents beginning in 2017. However, the city will continue to retain significant information about applicants, including their name, gender, address, birthdate, and the photo taken when the id was made.

The ID NYC program DOES NOT ask applicants about their immigration status. Nevertheless, because this program is well used by members of New York’s immigrant communities (according to the Gothamist, over a third of NYC residents are foreign-born), these applications could be used for fishing expeditions looking for our undocumented neighbors.

Yes, the Mayor has pledged to fight to keep this paperwork private. But we can’t be sure how the courts will act when push comes to shove.

The solution? Gum up the works.

Blast the program with lots and lots of applications from NYC residents so that any authority that does manage to subpoena applications has an immense archive to wade through. Estimates suggest that about 1 million people have applied for ID NYC to date. That leaves about 6.8 million New Yorkers who still can. (Yes, kids can apply, too, as long as they are 14.)

Applying is easy, though it will take you a little time. You start by making an appointment at one of the 25 enrollment centers. There’s a form to fill out (applications are available in more than 25 languages), that you can do ahead of time and print out or fill out when you get there. Bring along your documents. Once you check in, you wait for an agent to go over the application and take your picture and then you can arrange to receive the id in the mail or pick it up. I got mine at the Mid-Manhattan Library. I made the appointment about a month ahead of time, though there were appointments sooner, and waited less than an hour to see the agent. It was about as much hassle as mailing a package at the post office.

Maybe this isn’t the most effective form of resistance, but it is an easy one that may do some good.

I look forward to seeing you in the streets. And the public library. And MoMA.

To report incidents of discrimination or hate

- The Governor’s Office – 1-888-392-3644

- The Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs 311 or 212-788-7654. Translation is available. You can also go to www1.nyc.gov for many other resources for NYC immigrants.

Additional Resources

- ImmigrationLawHelp.org – Helps low-income immigrants find legal help.

- National Immigration Law Center: Explains your rights, no matter who is president.

- New York Immigrant Coalition and

- Make the Road: Provide policy updates and resources to support immigrants in NYC

- New York Communities for Change

- Causa Justa/Just Cause

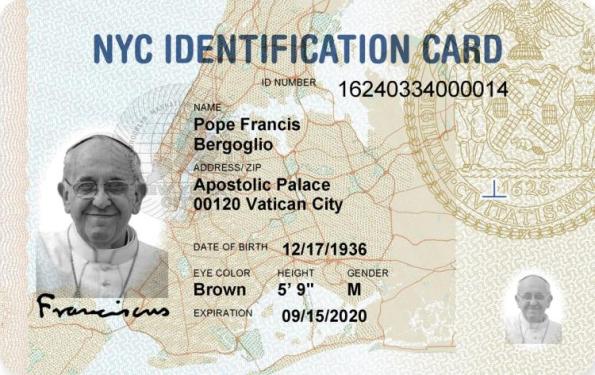

Immigrant protests #JFKTerminal4 and 2pm at Battery Park today

I was excited to join the protest at JFK Airport last night. Here’s some footage:

And here’s two nice pictures:

One of the cool things about the protest is how messages were sent and spread through the chants. In particular I learned about another planned protest today at Battery Park at 2pm, which I believe is being organized by immigrant rights group Make the Road.

More information available here.

By the way, in case you’ve heard that a judge put a stay on the Executive Order about immigrants, there are plenty of reasons to question that. It’s also possible that border patrol agents are not obeying those orders.

Bloomberg post: When Algorithms Come for Our Children

Hey all, my second column came out today on Bloomberg:

When Algorithms Come for Our Children

Also, I reviewed a book called Data for the People by Andreas Weigend for Science Magazine. My review has a long name:

Bloomberg View!

Great news! I’m now a Bloomberg View columnist. My first column came out this morning, and it’s called If Fake News Fools You, It Can Fool Robots, Too. Please take a look and tell me what you think!

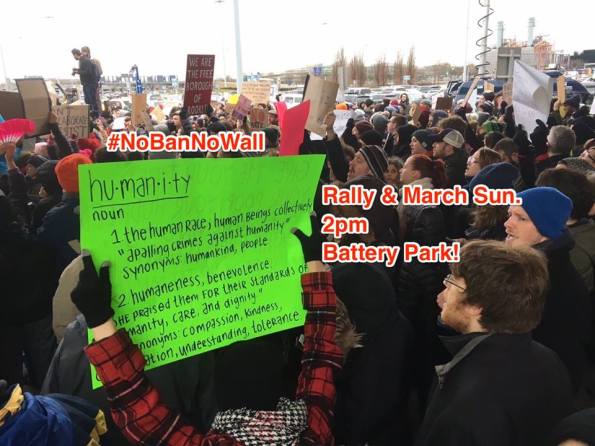

Pussyhats and the activist knitter

I finally got around to knitting my first pussyhat yesterday, during the inauguration. It took less than two hours because I was using super bulky yarn and because I had lots of anxious energy to tap into.

I got the yarn last Saturday, when I went to a Black Lives Matter march in the morning (you can see my butt multiple times in the embedded video) and then afterwards to Vogue Knitting Live in the Times Square Marriott Marquis.

And here’s the thing, I thought I was going to enjoy the juxtaposition of activist-to-insane hobbiest, but I was wrong – knitters were activists too! Here’s what I saw:

Pink yarn everywhere.

Pussyhats everywhere

Not only women of course! Alex looks dashing with his ombre pussyhat.

Karida Collins doesn’t have a pussyhat on but she’s still killing it.

Since last weekend, I’ve been seeing pussyhats everywhere. You go into a yarn store and here’s what you see.

Or you happen upon an airplane full of women heading to D.C. and here’s what you see.

I’m pretty sure half those women have knitting needles in their laps.

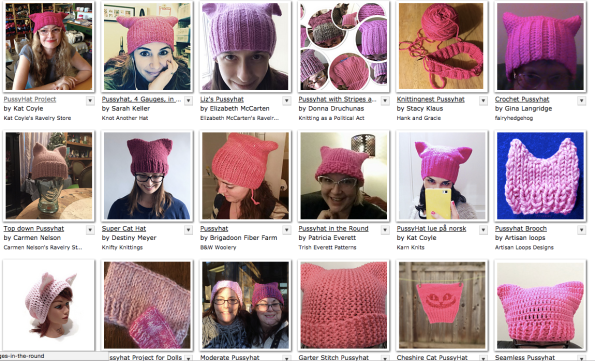

My favorite way to measure this phenomenon is directly, at the source. I am of course referring to Ravelry, the online social media website for knitters and crafters. The pussyhat project has spawned all sorts of creative ideas, of course.

The original pattern has thousands of associated projects

Lots of variations have been invented of course

Here’s a great example

Not particularly cat-like but I like it

Now that it’s happened, it’s obvious that knitters are a perfect community for activism. We’re friendly, community-oriented, and desperate for an opportunity to make something and give it away. Because it gives us an excuse to buy more yarn.

Anyhoo, I’m going to the Women’s March NYC today with mine, and I’m going to try to knit at least one more before I leave at 11am. See you there!

Two out of three “fairness” criteria can be satisfied

This is a continuation of a discussion I’ve been having with myself about the various definition of fairness in scoring systems. Yesterday I mentioned a recent paper entitled Inherent Trade-Offs in the Fair Determination of Risk Scores that has a proof of the following statement:

You cannot simultaneously ask for a model to be well-calibrated, to have equal false positive rates for blacks and whites, and to have equal false negative rates unless you are in the presence of equal “base rates” or a perfect predictor.

The good news is that you can ask for two out of three of these. Here’s a picture of a specific example of this, where I’ve simplified the situation so there are two groups of people being scores, B and W, and they each can be scored as either empty or full, and then the reality is that could either be empty or full. They have different “base rates,” which is to say that in reality, a different proportion of the B group is empty (70%) than the W group (50%). We insist, moreover, that the labeling scheme is “well-calibrated”, so the right proportion of them are labeled empty or full. I’ve drawn 10 “perfect representatives” from each group here:

In my picture, I’ve assumed there was some mislabeling – there’s a full in the empty bin and there are empties in the full bin. Because we are assuming the model is well-calibrated, every time we have one kind of mistake we have to make up for that mistake with exactly one of the other type. In the picture there’s exactly one of each mistake for both the W group and the B group, so that’s fine.

Quick calculation: in the picture above, the “false full rate”, which we can think of as the “false positive rate,” for B is 1/3 = 33% but the “false positive rate” for W is 1/5 = 20%, even though they each have only one mislabeled representative each.

Now it’s obvious that, theoretically, the scoring system could adjust the false positive rate for B to match that of W, which would mean having 3/5 of a representative be mislabeled. But again, that’d mean we would need only 3/5 of a representative be mislabeled in the empty bin as well.

That’s a false negative rate for B of 3/35 = 8.6% (note it used to be 1/7 = 14.3%). By contrast the false negative rate for A stays fixed at 1/5 = 20%.

If you think about it, what we’ve done is sacrificed some false negative rate balance for a perfect match on the false positive rate, while keeping the model well-calibrated.

Applying this to recidivism scores, we can ask for the high scores to reflect base rates for the populations, and we can ask for similar false positive rates for populations, but we cannot also ask for false negative rates to be equal. That might be better overall, though, because the harm that comes from unequal false positive rate – sending someone to jail for longer – is arguably more toxic than an unequal false negative rate, which means certain groups are let off the hook more often than the others.

By the way, I want to be clear that I don’t think recidivism risk algorithms should actually be the goal, summed up in this conversation I had with Tom Slee. I’m not even sure why their use is constitutional, to tell the truth. But given that they are in use, I think it makes sense to try to make them as good as possible, and to investigate what “good” means in this context.

Two clarifications

First, I think I over-reacted to automated pricing models (thanks to my buddy Ernie Davis who made me think harder about this). I don’t think immediate reaction to price changes is necessarily odious. I do think it changes the dynamics of price optimization in weird ways, but upon reflection I don’t see how they’d necessarily be bad for the general consumer besides the fact that Amazon will sometimes have weird disruptions much like the flash crashes we’ve gotten used to on Wall Street.

Also, in terms of the question of “accuracy versus discrimination,” I’ve now read the research paper that I believe is under consideration, and it’s more nuanced than my recent blog posts would suggest (thanks to Solon Barocas for help on this one).

In particular, the 2011 paper I referred defines discrimination crudely, whereas this new article allows for different “base rates” of recidivism. To see the different, consider a model that assigns a high risk score 70% of the time to blacks and 50% to whites. Assume that, as a group, blacks recidivate at a 70% rate and whites at a 50% rate. The article I referred to would define this as discriminatory, but the newer paper refers to this as “well calibrated.”

Then the question the article tackles is, can you simultaneously ask for a model to be well-calibrated, to have equal false positive rates for blacks and whites, and to have equal false negative rates? The answer is no, at least not unless you are in the presence of equal “base rates” or a perfect predictor.

Some comments:

- This is still unsurprising. The three above conditions are mathematical constraints, and there’s no reason to expect that you can simultaneously require a bunch of really different constraints. The authors do the math and show that intuition is correct.

- Many of my comments still hold. The most important one is the question of why the base rates for blacks and whites are so different. If it’s because of police practice, at least in part, or overall increased surveillance of black communities, then I’d argue “well-calibrated” is insufficient.

- We need to be putting the science into data science and examining questions like this. In other words, we cannot assume the data is somehow fixed in stone. All of this is a social construct.

This question has real urgency, by the way. New York Governor Cuomo announced yesterday the introduction of recidivism risk scoring systems to modernize bail hearings. This could be great if fewer people waste time in jail pending their hearings or trials, but if the people chosen to stay in prison are chosen on the basis that they’re poor or minority or both, that’s a problem.

Algorithmic collusion and price-fixing

There’s a fascinating article on the FT.com (hat tip Jordan Weissmann) today about how algorithms can achieve anti-competitive collusion. Entitled Policing the digital cartels and written by David J Lynch, it profiles a classic cinema poster seller that admitted to setting up algorithms for pricing with other poster sellers to keep prices high.

That sounds obviously illegal, and moreover it took work to accomplish. But not all such algorithmic collusion is necessarily so intentional. Here’s the critical paragraph which explains this issue:

As an example, he cites a German software application that tracks petrol-pump prices. Preliminary results suggest that the app discourages price-cutting by retailers, keeping prices higher than they otherwise would have been. As the algorithm instantly detects a petrol station price cut, allowing competitors to match the new price before consumers can shift to the discounter, there is no incentive for any vendor to cut in the first place.

We also don’t seem to have the legal tools to address this:

“Particularly in the case of artificial intelligence, there is no legal basis to attribute liability to a computer engineer for having programmed a machine that eventually ‘self-learned’ to co-ordinate prices with other machines.

How to fix recidivism risk models

Yesterday I wrote a post about the unsurprising discriminatory nature of recidivism models. Today I want to add to that post with an important goal in mind: we should fix recidivism models, not trash them altogether.

The truth is, the current justice system is fundamentally unfair, so throwing out algorithms because they are also unfair is not a solution. Instead, let’s improve the algorithms and then see if judges are using them at all.

The great news is that the paper I mentioned yesterday has three methods to do just that, and in fact there are plenty of papers that address this question with various approaches that get increasingly encouraging results. Here are brief descriptions of the three approaches from the paper:

- Massaging the training data. In this approach the training data is adjusted so that it has less bias. In particular, the choice of classification is switched for some people in the preferred population from + to -, i.e. from the good outcome to the bad outcome, and there are similar switches for some people in the discriminated population from – to +. The paper explains how to choose these switches carefully (in the presence of continuous scorings with thresholds).

- Reweighing the training data. The idea here is that with certain kinds of models, you can give weights to training data, and with a carefully chosen weighting system you can adjust for bias.

- Sampling the training data. This is similar to reweighing, where the weights will be nonnegative integer values.

In all of these examples, the training data is “preprocessed” so that you can train a model on “unbiased” data, and importantly, at the time of usage, you will not need to know the status of the individual you’re scoring. This is, I understand, a legally a critical assumption, since there are anti-discrimination laws which forbid you to “consider” the race of someone when deciding whether to hire them or so on.

In other words, we’re constrained by anti-discrimination law to not use all the information that might help us avoid discrimination. This constraint, generally speaking, prevents us from doing as good a job as possible.

Remarks:

- We might not think that we need to “remove all the discrimination.” Maybe we stratify the data by violent crime convictions first, and then within each resulting bin we work to remove discrimination.

- We might also use the racial and class discrepancies in recidivism risk rates as an opportunity to experiment with interventions that might lower those discrepancies. In other words, why are there discrepancies, and what can we do to diminish them?

- In other words, I do not claim that this is a trivial process. It will in fact require lots of conversations about the nature of justice and the goals of sentencing. Those are conversations we should have.

- Moreover, there’s the question of balancing the conflicting goals of various stakeholders which makes this an even more complicated ethical question.

Recidivism risk algorithms are inherently discriminatory

A few people have been sending me, via Twitter or email, this unsurprising article about how recidivism risk algorithms are inherently racist.

I say unsurprising because I’ve recently read a 2011 paper by Faisal Kamiran and Toon Calders entitled Data preprocessing techniques for classification without discrimination, which explicitly describes the trade-off between accuracy and discrimination in algorithms in the presence of biased historical data (Section 4, starting on page 8).

In other words, when you have a dataset that has a “favored” group of people and a “discriminated” group of people, and you’re deciding on an outcome that has historically been awarded to the favored group more often – in this case, it would be a low recidivism risk rating – then you cannot expect to maximize accuracy and keep the discrimination down to zero at the same time.

Discrimination is defined in the paper as the difference in percentages of people who get the positive treatment among all people in the same category. So if 50% of whites are considered low-risk and 30% of blacks are, that’s a discrimination score of 0.20.

The paper goes on to show that the trade-off between accuracy and discrimination, which can be achieved through various means, is linear or sub-linear depending on how it’s done. Which is to say, for every 1% loss of discrimination you can expect to lose a fraction of 1% of accuracy.

It’s an interesting paper, well written, and you should take a look. But in any case, what it means in the case of recidivism risk algorithms is that any algorithm that is optimized for “catching the bad guys,” i.e. accuracy, which these algorithms are, and completely ignores the discrepancy between high risk scores for blacks and for whites, can be expected to be discriminatory in the above sense, because we know the data to be biased*.

* The bias is due to the history of heightened scrutiny of black neighborhoods by police which we know as broken windows policing, which makes blacks more likely to be arrested for a given crime, as well as the inherent racism and classism in our justice system itself that was so brilliantly explained out by Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow, which makes them more likely to be severely punished for a given crime.

2017 Resolutions: switch this shit up

Don’t know about you, but I’m sick of New Year’s resolutions, as a concept. They’re flabby goals that we’re meant not only to fail to achieve but to feel bad about personally. No, I didn’t exercise every single day of 2012. No, I didn’t lose 20 pounds and keep it off in 1988.

What’s worst to me is how individual and self-centered they are. They make us focus on how imperfect we are at a time when we should really think big. We don’t have time to obsess over details, people! Just get your coping mechanisms in place and do some heavy lifting, will you?

With that in mind, here are my new-fangled resolutions, which I full intend to keep:

- Let my kitchen get and stay messy so I can get some goddamned work done.

- Read through these papers and categorize them by how they can be used by social justice activists. Luckily the Ford Foundation has offered me a grant to do just this.

- Love the shit out of my kids.

- Keep up with the news and take note of how bad things are getting, who is letting it happen, who is resisting, and what kind of resistance is functional.

- Play Euclidea, the best fucking plane geometry app ever invented.

- Form a cohesive plan for reviving the Left.

- Gain 10 pounds and start smoking.

Now we’re talking, amIright?

Kindly add your 2017 resolutions as well so I’ll know I’m not alone.

Creepy Tech That Will Turbocharge Fake News

My buddy Josh Vekhter is visiting from his Ph.D. program in computer science and told me about a couple of incredibly creepy technological advances that will soon make our previous experience of fake news seem quaint.

First, there’s a way to edit someone’s speech:

Next, there’s a way to edit a video to insert whatever facial expression you want (I blame Pixar on this one):

Put those two technologies together and you’ve got Trump and Putin having an entirely fictitious but believable conversation on video.

Section 230 isn’t up to the task

Today in my weekly Slate Money podcast I’m discussing the recent lawsuit, brought by the families of the Orlando Pulse shooting victims, against Facebook, Google, and Twitter. They claim the social media platforms aided and abetted the radicalization of the Orlando shooter.

They probably won’t win, because Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 protects internet sites from content that’s posted by third parties – in this case, ISIS or its supporters.

The ACLU and the EFF are both big supporters of Section 230, on the grounds that it contributes to a sense of free speech online. I say sense because it really doesn’t guarantee free speech at all, and people are kicked off social media all the time, for random reasons as well as for well-thought out policies.

Here’s my problem with Section 230, and in particular this line:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider

Section 230 treats “platforms” as innocent bystanders in the actions and words of its users. As if Facebook’s money-making machine, and the design of that machine, have nothing to do with the proliferation of fake news. Or as if Google does not benefit directly from the false and misleading information of advertisers on its site, which Section 230 immunizes it from.

The thing is, in this world of fake news, online abuse, and propaganda, I think we need to hold these platforms at least partly responsible. To ignore their contributions would be foolish from the perspective of the public.

I’m not saying I have a magic legal tool to do this, because I don’t, and I’m no legal scholar. It’s also difficult to precisely quantify the externalities of the kinds of problems stemming from a complete indifference and immunization from consequences that the platforms currently enjoy. But I think we need to do something, and I think Section 230 isn’t that thing.

How do you quantify morality?

Lately I’ve been thinking about technical approaches to measuring, monitoring, and addressing discrimination in algorithms.

To do this, I consider the different stakeholders and the relative harm they will suffer depending on mistakes made by the algorithm. It turns out that’s a really robust approach, and one that’s basically unavoidable. Here are three examples to explain what I mean.

- AURA is an algorithm that is being implemented in Los Angeles with the goal of finding child abuse victims. Here the stakeholders are the children and the parents, and the relative harm we need to quantify is the possibility of taking a child away from parents who would not have abused that kid (bad) versus not removing a child from a family that does abuse them (also bad). I claim that, unless we decide on the relative size of those two harms – so, if you assign “unit harm” to the first, then you have to decide what the second harm counts as – and then optimize to it using that ratio in the penalty function, then you cannot really claim you’ve created a moral algorithm. Or, to be more precise, you cannot say you’ve implemented an algorithm in line with a moral decision. Note, for example, that arguments like this are making the assumption that the ratio is either 0 or infinity, i.e. that one harm matters but the other does not.

- COMPAS is a well-known algorithm that measures recidivism risk, i.e. the risk that a given person will end up back in prison within two years of leaving it. Here the stakeholders are the police and civil rights groups, and the harms we need to measure against each other are the possibility of a criminal going free and committing another crime versus a person being jailed in spite of the fact that they would not have gone on to commit another crime. ProPublica has been going head to head with COMPAS’s maker, Northpointe, but unfortunately, the relative weight of these two harms is being sidestepped both by one side and the other.

- Michigan recently acknowledged its automated unemployment insurance fraud detection system, called Midas, was going nuts, accusing upwards of 20,000 innocent people of fraud while filling its coffers with (mostly unwarranted) fines, which it’s now using to balance the state budget. In other words, the program deeply undercounted the harm of charging an innocent person with fraud while it was likely overly concerned with missing out on a fraud fine payment that it deserved. Also it was probably just a bad program.

If we want to build ethical algorithms, we will need to weight harms against each other and quantify their relative weights. That’s a moral decision, and it’s hard to agree on. Only after we have that difficult conversation can we optimize our algorithms to those choices.

Facebook, the FBI, D&S, and Quartz

If you’re wondering why I don’t write more blog posts, it’s because I’m writing for other stuff all the time now! But the good news is, once those things are published, I can talk about them on the blog.

- I wrote a piece about the Facebook algorithm versus democracy for Nova. TL;DR: Facebook is winning.

- Susan Landau and I wrote a letter to respond to a bad idea about how the FBI should use machine learning. Both were published on the LawFare blog.

- The kind folks at Data & Society met up, read my book, and wrote a bunch of fascinating responses to it.

- Nikhil Sonnad from Quartz published a nice interview with me yesterday and brought along a photographer.