Archive

HCSSiM Workshop day 15

This is a continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

Aaron was visiting my class yesterday and talked about Sandpiles. Here are his notes:

Sandpiles: what they are

For fixed , an

beach is a grid with some amount of sand in each spot. If there is too much sand in one place, it topples, sending one grain of sand to each of its neighbors (thereby losing 4 grains of sand). If this happens on an edge of the beach, one of the grains of sand falls off the edge and is gone forever. If it happens at a corner, 2 grains are lost. If there’s no toppling to do, the beach is stable. Here’s a 3-by-3 example I stole from here:

Do stable beaches form a group?

Answer: well, you can add them together (pointwise) and then let that stabilize until you’ve got back to a stable beach (not trivial to prove this always settles! But it does). But is the sum well-defined?

In other words, if there is a cascade of toppling, does it matter what order things topple? Will you always reach the same stable beach regardless of how you topple?

Turns out the answer is yes, if you think about these grids as huge vectors and toppling as adding other 2-dimensional vectors with a ‘-4’ in one spot, a ‘1’ in each of the four spots neighboring that, and ‘0’ elsewhere. It inherits commutativity from addition in the integers.

Wait! Is there an identity? Yep, the beach with no sand; it doesn’t change anything when you add it.

Wait!! Are there inverses? Hmmmmm….

Lemma: There is no way to get back to all 0’s from any beach that has sand.

Proof. Imagine you could. Then the last topple would have to end up with no sand. But every topple adds sand to at least 2 sites (4 if the toppling happens in the center, 3 if on an edge, 2 if on a corner). Equivalently, nothing will topple unless there are at least 4 grains of sand total, and toppling never loses more than 2 grains, so you can never get down to 0.

Conclusion: there are no inverses; you cannot get back to the ‘0’ grid from anywhere. So it’s not a group.

Try again

Question: Are there beaches that you can get back to by adding sand?

There are: on a 2-by-2 beach, the ‘2’ grid (which means a 2 in every spot) plus itself is the ‘4’ grid, and that topples back to the ‘2’ grid if you topple every spot once. Also, the ‘2’ grid adds to the grid and gets it back.

Wow, it seems like the ‘2’ grid is some kind of additive identity, at least for these two elements. But note that the ‘1’ grid plus the ‘2’ grid is the ‘3’ grid, which doesn’t topple back to the ‘1’ grid. So the ‘2’ grid doesn’t work as an identity for everything.

We need another definition.

Recurrent sandpiles

A stable beach C is recurrent if (i) it is stable, and (ii) given any beach A, there is a beach B such that C is the stabilization of A+B. We just write this C = A+B but we know that’s kind of cheating.

Alternative definition: a stable beach C is recurrent if (i) it is stable, and (ii) you can get to C by starting at the maximum ‘3’ grid, adding sand (call that part D), and toppling until you get something stable. C = ‘3’ + D.

It’s not hard to show these definitions are equivalent: if you have the first, let A = ‘3’. If you have the second, and if A is stable, write A + A’ = ‘3’, and we have B = A’ + D. Then convince yourself A doesn’t need to be stable.

Letting A=C we get a beach E so C = C+E, and E looks like an identity.

It turns out that if you have two recurrent beaches, then if you can get back to one using a beach E then you can get back to to the other using that same beach E (if you look for the identity for C + D, note that (C+D)+E = (C+E) + D = C+D; all recurrent beaches are of the form C+D so we’re done). Then that E is an identity element under beach addition for recurrent beaches.

Is the identity recurrent? Yes it is (why? this is hard and we won’t prove it). So you can also get from A to the identity, meaning there are inverses.

The recurrent beaches form a group!

What is the identity element? On a 2-by-2 beach it is the ‘2’ grid. The fact that it didn’t act as an identity on the ‘1’ grid was caused by the fact that the ‘1’ grid isn’t itself recurrent so isn’t considered to be inside this group.

Try to guess what it is on a 2-by-3 beach. Were you right? What is the order of the ‘2’ grid as a 2-by-3 beach?

Try to guess what the identity looks like on a 198-by-198 beach. Were you right? Here’s a picture of that:

We looked at some identities on other grids, and we watched an app generate one. You can play with this yourself. (Insert link).

The group of recurrent beaches is called the m-by-n sandpile group. I wanted to show it to the kids because I think it is a super cool example of a finite commutative group where it is hard to know what the identity element looks like.

You can do all sorts of weird things with sandpiles, like adding grains of sand randomly and seeing what happens. You can even model avalanches with this. There’s a sandpile applet you can go to and play with.

HCSSiM Workshop, day 14

This is a continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

We switched it up a bit and I went to talk about Rubik’s Cubes in Benji Fisher’s classroom whilst Aaron Abrams taught in mine and Benji taught in Aaron’s. We did this so we could meet each other’s classes and because we each had a presentation that we thought all the classes might want to see.

In my class, besides what Aaron talked about (which I hope to blog about tomorrow), we talked about representing groups with generators and relations and we looked at how to create fractals on the complex plane using Mathematica.

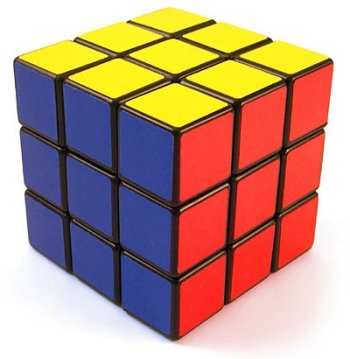

Solving the Rubik’s Cube with group theory

First I talked about the position game, so ignoring orientation of the pieces. In other words, if all the pieces are in the correct position but are twisted or flipped, that’s ok.

Consider the group acting on the set which is the Rubik’s cube. We can fix the centers, and then this group is clearly generated by 90 degree clockwise turns on each of the 6 faces (clockwise when you look straight at the center of the face). It has a bunch of relations too, of course, including (for example) that the “front” move commutes with the “back” move and that any of these generators is trivial if you do it 4 times in a row.

Next we noted that the 8 corners always move to other corners on any of these moves, and that the 12 edges always move to edges. So we could further divide the “positions game” into an “edges game” and a “corners game.” Furthermore, because of this separation, any action can be realized as an element of the group

But there’s more: any one of these generators is a 4-cycle on both edges and corners, which is odd in both cases, so so is a product of the generators. This means the group action actually lands inside

where I denote by the odd permutations of

Next I stated and proved that the 3-cycles generate , by writing any product of two transpositions as a product of two or three 3-cycles.

The reason that’s interesting is that, once I show that I can act by arbitrary 3-cycles on the edges or corners, this means I get that entire group up there of the form (even, even) or (odd, odd).

Next I demonstrated a 3-cycle on three “bad pieces” where one needs to go into the position of one of the other two. Namely:

- Put two “bad” pieces on the top and one below, including the piece which is the destination of the third.

- Do some move U which moves the third bad piece below to its position on the top without changing anything else.

- Move the top so you decoy the new piece with the other bad piece on top. Call this decoy move V.

- Undo the U move.

- Undo the V move.

Seen from the perspective of the top, all that happens is that suddenly it has one piece in the right place (after U), then it gets rid of a piece it didn’t want anyway. From the perspective of the bottom, it sent up a piece it didn’t want to the top, then unmessed itself by taking back another piece from the top.

That’s a 3-cycle on the pieces, on the one hand (and a commutator on the basic moves), and we can perform it on any three corners or edges by first performing some move to get 2 out of the 3 pieces on the same face and the third not on that face. This is essentially acting by conjugation (and it’s still a commutator).

Moreover, the overall effect on the puzzle is that it took 3 pieces that were messed up and got at least 1 in the right spot.

The overall plan now is that you solve the corners puzzle, then the edges puzzle, and you’re done. Specifically, I get to the (even, even) situation by turning one face once if necessary, and then I can perform arbitrary 3-cycles to solve my problem. If I have fewer than three messed up corners (resp. edges), then I have either 0, 1, or 2 messed up corners (resp. edges). But I can’t have exactly 1, and exactly 2 would be odd, so I have 0.

That’s the position game, and I’ve given an algorithm to solve it (albeit not efficient!).

What about the orientations?

Shade the left and right side of a solved cube. Both the position (cubicle) and the piece of plastic (cubie) can be considered as shaded. Also shade a strip on the front and on the back, so we get the top and bottom edge of the front and back shaded.

Convince yourself that every edge and every corner position has exactly one shaded face.

When the cube is messed up, the shaded face of the position may not coincide with the shaded face of the cubie in that position. For edges it’s either right or wrong – assign each a value of 0 (if it’s right) or 1 (if it’s wrong). These can be considered orientation values modulo 2.

For corners, it can be wrong in two ways. The cubie’s shaded face could coincide with the position’s shaded face (give it a value 0), or it could be clockwise 120 degrees (value 1), or counterclockwise 120 degrees (value -1). These numbers are modulo 3.

Next, convince yourself that all of the generators of the group of actions on the rubik’s cube preserve the fact that the sum of the orientation numbers is 0, considered either mod 3 for the corners or mod 2 for the edges.

In particular, this means we can’t have exactly one edge flipped but everything in the right position. If you see this on a Rubik’s cube then someone took it apart and put it back together wrong.

However, you can twist one corner clockwise and another one counterclockwise, which means you can get any configuration of orientation numbers on the corners that satisfy that their sum is 0. Same with edges – it’s possible to flip two.

Finally, I exhibit how to do each of these basic orientation moves by 2 3-cycles. First I choose a pivot corner and perform a 3-cycle on those three corners, and then I do another 3-cycle, which uses the same 3 corners but is slightly different and results in everything being back in the right position but two corners twisted. I can do the same thing for edges, and I have thus totally solved the cube.

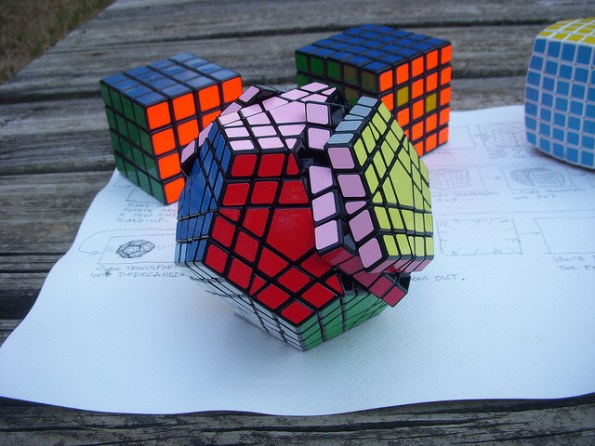

This method of 3-cycles is slow but it generalizes to all Rubik’s puzzles, so for example the 7 by 7 cube:

Or, with some work, something else like this:

p.s. I learned all of this when I was 15 from Mike Reid at HCSSiM 1987.

p.p.s. This was what we ate after singing our Yellow Pig Carols last night:

HCSSiM Workshop, day 13

This is a continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

Permutation notation

Using a tetrahedron as inspiration, we found the group of rotational symmetries as a subgroup of the permutation group We then spent a lot of time discussing how to write good notation for permutations, coming up finally with the standard form but complaining about how multiplication is in a weird direction, stemming from the composition rule

Quadratic Reciprocity

Today we proved quadratic reciprocity, which totally rocks. In order to get there we needed three lemmas, which were essentially a bunch of different formulas for computing the Jacobi symbol.

The first was that, modulo we have:

The second one was that we could write as -1 to the

, where

is the number of negative numbers you get when you write the numbers

modulo

with a number of absolute value less than

In the third one we assume is odd (we deal with

separately). We prove we can write

as -1 to the

, where

is (also) the sum of the greatest integers

for

Each of these lemmas, in other words, gave us different ways to compute the symbol . They are each pretty easy to prove:

The first one uses the fact that if is not a square, then the product of all nonzero numbers mod

can be paired up into

pairs of different numbers whose product is

, so we get altogether

but on the other hand we already know by Wilson’s Theorem that that product is -1.

The second one just uses the fact that, ignoring negative signs, is the same list as

but paying attention to negative signs we can take out an

and also a

Since we already know the first lemma we’re done.

The third lemma follows from repeatedly applying the division algorithm to and

, so writing

for all . We replace the remainders by the previous form of “small representatives” which we call

modulo

, making the remained positive or negative but smaller than

this replacement requires that we add

. We add all the division formulas up and realize that we only need to care about the parity of

so in other words we work modulo 2. It looks like this:

Since is odd, we can ignore it modulo 2. Since

is odd same there. We get:

Up to signs, so we can conclude our lemma.

Incidentally, using the formula above (before we ignore ) it’s also easy to see that

Finally, we show that the sum is just the number of lattice points in the region above the x-axis, to the left of the line

and below the line

But, letting some other odd prime, we can do the same exact thing and we find that

is just the number of lattice points in the region above the x-axis, to the left of the line

and below the line

Flipping the second triangle over the line

demonstrates that we have two halves of the rectangle with

lattice points. Here’s the picture for

and

(ignore the dotted lines):

Alternating Group

We introduced cyclic notation, showing everything is a product of transpositions, then we introduced the sign function and showed that can only be written as a product of an even number of transpositions. This means the sign function is well defined, and it’s easy to see then that it’s a homomorphism, so we can define its kernel to be the alternating group.

Transformation of the Plane

We discussed rotations, shears, shrinks, reflections, and translations of the plane and demonstrated them in Mathematica using this.

Yellow Pig Carols

Tomorrow is Yellow Pig Day, which is a yearly tradition here at HCSSiM during which we celebrate our mascot the yellow pig and our favorite number, 17.

In particular, there will be an hour and a half lecture during which we will hear many surprising and elegant 17 facts (examples: the longest time anybody has ever sat in a tub of ketchup? 17 hours. The average adolescent male has a sexually related thought how often? Every 17 seconds).

Some time after the 17 lecture we get together to sing Yellow Pig Carols. These are usually set to the tune of some song, with the lyrics changed to refer to math, in particular the number 17, and yellow pigs, Weird Al Yankovic- style. Check out this list for a taste.

But there’s a problem, which is that the songs are really old and many of the tunes are unknown to this crop of kids. In desperate need of a revamp, I got my workshop to write a new song, which I’m super proud of. We started out by voting on a song (winner: Somewhere Over the Rainbow) for which we wrote new lyrics. Here they are:

Some July Seventeenth

Some july seventeenth

when pigs fly

we’ll see patches of yellow

scattered across the sky

Some “f” over the reals

satisfy

f of x plus f of y

is f-of-x plus y

someday I’ll find another g

besides f of t is k t or zer-o

and then I will compose the two

and get solutions that are new

they’ll appear-o

Some groups they are abelian

they commute

but some have commutators

whose actions are not moot

The action on the complex plane

by matrices is so in-sanely dum-ber

than even that of conjugation

whose equivalence relation pairs the num-bers

Some july seventeenth

when pigs fly

we’ll see patches of yellow

scattered across the sky

Honestly I thought it would stop there, but people around here have been on a tear. My hilarious junior staff Maxwell Levit has written a brilliant song based on Gotye’s “Somebody I Used to Know”. If you haven’t been living under a rock, you will have heard that song (and if you haven’t heard that song, please go ahead and do so now), about a guy wondering why this woman has left him and won’t talk to him, and then she comes in and tells her story which is how much of a manipulative creep he really was. There’s a dramatic video featuring nakedness and body paint which adds to the drama and to the song.

Well Max just turned that shit around and now it’s Fermat singing to Fermat’s Last Theorem, wondering where he went wrong, and then the theorem talks back and tells us the real deal. Plus he uses the word “marginalia,” which is in itself awesome. Here it is:

A Theorem that I used to know

(Fermat)

Now and then I think of Diophantine equations

Like how Pythagoras showed the case for n=2

Told myself that I understood,

And didn’t write down what I thought I would

Remember when I looked back at my marginalia

You can get addicted to a certain type of hubris

Assuming you don’t need to use elliptic curves

So when I found my proof did not make sense,

I knew it wasn’t my incompetence

But I’ll admit I was confused to say the least.

But you didn’t have to be so hard,

Make out like my intuitive method was for nothing

I don’t even need to know

But they treat you like Wiles solved you and that feels so rough

No you didn’t have to stoop so low

Elliptic curves and modular forms lack in imagination

I guess I don’t need you though,

Now you’re just some theorem that I used to know.

Now you’re just some theorem that I used to know.

Now you’re just some theorem that I used to know.

(theorem)

Now and then I think of when you said you’d solved me.

Part of me believing I had some marvelous proof.

But I don’t really work that way.

Adhering to everything you say.

You said that you could let it go,

And you shouldn’t get too hung up on a theorem that you used to know!

(Fermat)

But you didn’t have to be so hard,

Make out like my intuitive method was for nothing

I don’t even need to know

But they treat you like Wiles solved you and that feels so rough

No you didn’t have to stoop so low

Elliptic curves and modular forms lack in imagination

I don’t even need you though,

Now you’re just some theorem that I used to know.

[x2]

Some Theorem!

(I used to know)

Some Theorem!

(Now you’re just some theorem that I used to know)

(I used to know)

(That I used to know)

(I used to know)

Some Theorem!

We’re gonna make Devin Ivy, a fantastically funny junior staff here as well as a photographer, play Gotye/ Fermat in the video, with yellow pigs getting continually plastered all over his body. He’s Gotye’s spitting image:

HCSSiM Workshop, day 12

This is a continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

We originally defined as

and now we re-introduce it as the set of matrices of the form with the obvious map where

is sent to:

After we reminded people about matrix addition and multiplication, we showed this was an injective homomorphism under addition and also jived with the multiplication that we knew coming from Overall our lesson was not so different from this one.

Then we talked about actions on the plane including translations and scaling and showed that under the above map, “multiplication by ” or by its corresponding matrix gives us the same thing.

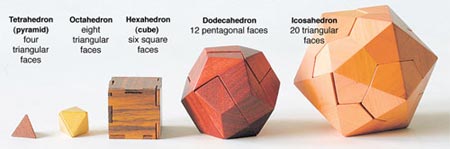

Platonic Solids

We went over the 5 platonic solids from yesterday- we’d proved it was impossible to have more than 5, and now it was time to show all 5 are actually possible! That’s when we whipped out Wayne Daniel’s “all five” puzzle:

We then introduced the concept of dual graph, and showed which platonic solids go to which under this map. We saw an example of a toy which flips from one platonic solid (cube) to its dual (octahedron) when you toss it in the air, the Hoberman Flip Out.

Here is it in between states:

Finally, we talked about symmetries of regular polyhedra and saw how we could embed an action into the group of symmetries on its vertices. So symmetries on tetrahedra is a subgroup of . It’s a lot easier to understand how to play with 4 numbers than to think about moving around a toy, so this is a good thing. Although it’s more fun to play with a toy.

Then one of our students, Milo, showed us how he projected a tiling of the plane onto the surface of a sphere using the language “processing“. Unbelievable.

After that we went to an origami workshop to construct yellow pigs as well as platonic solid type structures.

HCSSiM Workshop, day 11

This is a continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

Lagrange

We reminded people that a finite group is a finite set with an associative multiplication law “*”, and an identity and inverses with respect that law. A subgroup is a subset which is a group in its own right with the same multiplication law. Given a subgroup of a group

we defined the cosets of

to be, for some

of the form:

We proved that “being in the same coset as” is an equivalence relation and that each coset has the same size. Altogether the cosets form a partition of the group, so the size of the group is the product of the size of any coset and the number of cosets.

One of the students decided that you could form a group law on the set of cosets, inheriting the multiplication operation from When it didn’t quite work out, he postulated that he could do it if the group is commutative. Pretty smart kid.

Primitive Roots modulo p

Next we spent more time than you’d think proving there’s a nonzero number modulo

whose powers generate all of the nonzero elements modulo

In other words, that there is an isomorphism

The left group is a group under multiplication, and the right one is a group under addition, which means this can be seen as a kind of logarithm in finite groups. Indeed an element on the left is mapped to that power

of

such that

So it’s very much like a logarithm.

To prove such an exists, we actually show that

such roots exist, and that in fact there are

th roots of unity for any

which divides

Another case where it helps to prove something harder than what you actually want.

To do that, we have a few lemmas. First, that there are at most roots to a degree

polynomial modulo

unless it’s the “zero” polynomial. Second, that if there’s a polynomial which achieves this maximum, it must divide the “Fermat’s Little Theorem” polynomial

These two lemmas aren’t hard.

Next we proved that there are at most primitive

th roots of unity for any

by showing that, if we had one, then we’d take certain powers to get all

of them, and then if we hadn’t counted one then we’d be able to produce too many roots of the polynomial

Finally, we wrote out boxes labeled with the divisors of and we labeled

balls the non-zero numbers mod

We put a ball with label

into the box with its order (the smallest positive number

so that

). Since there are at most

in each box, and since we need to put every ball in some box, there must be exactly

balls in each box since we proved a few days ago that:

Platonic Solids

Riffing on our proof of Euler’s formula for planar graphs, we convinced the kids that we could just as well consider a graph to be on a sphere, using a stereographic projection.

Then, using graphs on spheres as guides, we looked at how many examples we could come up with for a regular polytope, where each face has the same number of edges and each vertex has the same number of edges leaving it. We came up with the five platonic solids.

HCSSiM Workshop day 10

This is a continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

Quadratic equations modulo p

We looked at the general quadratic equation modulo an odd prime

(assume

) and asked when it has roots. We eventually found the solution to be similar to the one we recognize over the reals, except you need to multiply by

instead of dividing by

. In particular, we achieved the goal, which was to reduce this general form to a question of when a certain thing (in this case

) is a square modulo

, in preparation for quadratic reciprocity.

We then defined the Jacobi symbol and proved that

or

.

Cantor

We then reviewed some things we’d been talking about in terms of counting and cardinality, we defined the notation for sets: we define

to mean “exists an injection from

to

“. We showed it is a partial ordering using Cantor-Schroeder-Bernstein.

Then we used Cantor’s argument to show the power set of a set always has strictly bigger cardinality than the set.

Euler and planar graphs

At this point the CSO (Chief Silliness Officer) Josh Vekhter took over class and described a way of assessing risk for bank robbers. You draw out a map of a bank as a graph with vertices in the corners and edges as walls. It can look like a tree, he said, but it would be a pretty crappy bank. But no judgment. He decided that, from the perspective of a bank robber, corners are good (more places to hide), rooms are good (more places for money to be stashed) but walls are bad (more things you need to break through to get money.

With this system, and assigning a -1 to every wall and a 1 to every corner or room, the overall risk of a bank’s map consistently looks like 2. He proved this is always true using induction on the number of rooms.

HCSSiM Workshop day 9

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

First we had a few proofs from the previous night’s problem set, including a proof of Hall’s Marriage Problem using Dilworth’s Theorem.

Counting stuff

We then proved an uncountable set union a countable set is uncountable, with the help of Lior’s comment from yesterday.

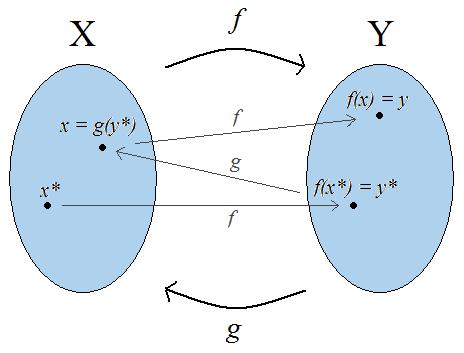

Then we proved the Cantor-Schroeder-Bernstein Theorem, which states that if you have two injective maps and

in the opposite directions:

and

then you can construct a bijection between

and

, and in particular the two sets will have the same cardinality. It’s not that hard – consider the orbits of points in X and Y under repeated applications of the two injective maps

, and if possible, by pulling back by

and

It doesn’t take much thinking to convince yourself that these orbits come in three forms: an infinite list in both directions, a finite loop, or an infinite forward path but a finite backwards path, where at some point you can’t pull back any more. In the last case you could get “stuck” in either or

Since the orbits form a partition of all of the points, you can independently decide how to define the bijection depending on what that orbit looks like. Namely, it takes an element

in

to

unless it’s an orbit that gets going backwards in

in which case you take

to

Now that I think of it, I’m pretty sure this proof uses the axiom of choice, and according to the wikipage on this theorem it doesn’t need to, but I don’t know a proof which avoids it. The truth is I can never tell. Please explain to me if you can, how you can verify if you’re using the axiom of choice in an argument where you make infinitely many decisions.

Homomorphisms

We defined a homomorphism of groups and wrote it in both additive and multiplicative notation, because it turns out some of the students were getting confused. We proved very basic properties that follow such as the fact that the identity element goes to the identity element under a homomorphism, and the image of the inverse of an element is the inverse of the image. We ended by asking them to consider the set of homomorphisms between a cyclic group of 6 elements and itself, or between a cyclic group of 6 elements to a cyclic group of 7 elements.

Fermat and Wilson

Next we whipped out some theorems modulo a prime We looked at the action defined on numbers mod 17 when you multiply them by 3, and noticed it just scrambles the non-zero ones up (and of course sends 0 to 0). We proved that this is true in general. But this means that the product of all the non-zero numbers mod p is the same if we pre-multiply by any

, which means that product is equal to itself times

and since it’s invertible that means

That’s just a hop skip and jump away from Fermat’s Little Theorem, which states that

for every number

.

Next, we wondered, what was that product of all those non-zero numbers mod ? It turns out that each of those nonzero guys is invertible, so if you pair each up with its inverse their contribution to the product is just 1, and the leftovers are just the guys who are their own inverse, which is only 1 or -1 (which we proved, and which is most definitely not true modulo 8). So the whole product is -1. That’s Wilson’s Theorem, but we called it Wilevson’s Theorem since Lev came up with the argument.

Mathematicians know how to admit they’re wrong

One thing I discussed with my students here at HCSSiM yesterday is the question of what is a proof.

They’re smart kids, but completely new to proofs, and they often have questions about whether what they’ve written down constitutes a proof. Here’s what I said to them.

A proof is a social construct – it is what we need it to be in order to be convinced something is true. If you write something down and you want it to count as a proof, the only real issue is whether you’re completely convincing.

Having said that, there are plenty of methods of proof that have been standardized and will help you in your arguments. There are things like proof by contradiction, or the pigeon hole principle, or proof by induction, or taking cases.

But in the end you still need to convince me; if you say there are three cases to consider, and I find a fourth, then I’ve blown away your proof, even if your three cases looked solid. If you try to prove something by induction, but your inductive step argument fails going from the case n=16 to n=17, then it’s not a proof.

Ultimately, then, a proof is a description of why you think something is true. The first half of your training is to problem solve (so, come up with a reason something is true) and construct a really convincing argument.

Coming at it from the other side, how can you check that what you’ve got is really a proof if you’ve written down the reason you think it’s true? That’s when the other half of your training comes in, to poke holes in arguments.

To be a really good mathematician you need to be a skeptic and to walk around with a metaphorical gun to shoot holes in other people’s arguments. Every time you hear a reasoned explanation, you look for the cases it doesn’t cover or the assumptions it’s making.

And you do the same thing with your own proofs to help yourself realize your mistakes before looking like a fool. Because putting out a proof of something is tantamount to asking for other people to shoot holes in your argument.

For that reason, every proof that one of these young kids offers up is an act of courage. They don’t know exactly how to explain their thinking, nor do they yet know exactly how to shoot holes in arguments, including their own. It’s an exercise in being wrong and admitting it. They are being trained to get shot down, to admit their mistake, and then immediately get back up again with better reasoning. The goal is to get so good at being wrong that it doesn’t hurt, that it’s not taken personally, and that it’s even fun to be wrong and to improve your argument.

Not every person gets trained in being wrong and admitting it. I’d wager that most people in the world, for most of their professional lives, are trained to do the opposite in the face of being wrong: namely, to wriggle out of it or deflect criticism. Most disciplines spend more time arguing they’re right, or at least not as wrong, or at least they have different mistakes, than other related fields. In math, you can at the most argue that what you’re doing is more interesting or somehow more important than some other field.

[I’ve never understood why people would think certain math is more important than other math. It’s almost never on the basis of having applications in the real world, or helping people in some way. It’s just some arbitrary snobbery, or at least that’s how it’s seemed. For my part I can’t explain why I love number theory more than analysis, it’s pure sense of smell.]

Most people never even say something that’s provably wrong in the first place. And that makes it harder to prove they’re wrong, of course, but it doesn’t mean they’re always right. Since they’ve not let themselves get pinned down on a provably wrong thing, they tend to stick with their wrong ideas for way too long.

I’m a huge fan of skepticism, and I think it’s generally undervalued. People who run companies, or universities, or government agencies, typically say they like healthy skepticism but actually want people to drink the kool aid. People who are skeptical are misinterpreted as being negative, but there’s a huge difference: negative means you’re not trying to solve the problem, skeptical means you care enough about the problem to want to solve it for real.

Now that I’ve thought about the training I’ve received as a mathematician, though, and that I’m now giving that training to these new students, I’ll add this to my defense of skepticism: I’m also a huge fan of people being able to admit they’re wrong. It’s the flip side of skepticism, and it’s why things get better instead of stay wrong.

By the way, one caveat: I’m not claiming that mathematicians are any better at admitting they’re wrong outside a strictly logical sphere.

HCSSiM Workshop day 8

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

We first saw presentations from the students from last night’s problem set. One was a four line proof that the last two digits of are 61. The other was a beautiful proof that the only real numbers that have more than one decimal representation are rationals of the form

for some integer

Dillworth’s Theorem Revisited

After going over examples of chains and antichains, and making sure we knew that there must be at least as many chains as there are elements in an anti-chains if we want the chains to cover our set, we set up a proof by induction on the number of elements in our set. The base case is easy (one element, one chain, one element in a maximal anti-chain) and then to reduce to a smaller case we remove any maximal element . Note this just means there’s nothing above it. But now the inductive hypothesis holds, and we cover the remaining set with chains

and moreover we define

to be the largest element in

such that it is contained in some maximal anti-chain.

We then stated two lemmas. The first is that any maximal anti-chain must have a unique element in each chain $C_i$, and the second is that, after defining the elements as above, they form a maximal anti-chain. We treat these lemmas as black boxes for the proof (the first we did yesterday, the second is on problem set tonight).

Now we put back the removed point There are two cases, either

is incomparable to any of the

‘s or it is comparable to at least one of them.

In the first case, we have an anti-chain of size namely the

‘s plus

, and we can form a

st chain consisting of just

itself.

In the second case, is comparable to some

Since

is maximal, and since

is maximal in its chain

with respect to being in a maximal antichain, we can form a new chain which is just the same thing as

for

and below, and goes straight up to

from

Note we may be missing some stuff that used to be above

in

But that doesn’t matter, because if we remove this new chain, we see that the maximal anti-chains leftover is only of size

so by Strong Induction we can cover it with

chains, and then bring back this chain to get an overall covering with

chains.

Dihedral Groups

After reviewing the formal definition of a Karafiol (group), we used rotations and flips of a folder and then of a regular 5-gon to come up with a non-commutative group. We defined a subgroup and explored the different subgroups of the dihedral group as well as other examples we’d seen coming from modular arithmetic.

Euler’s Totient function

We introduced the number of positive integers less than relatively prime to

as a function of

called

and wrote out a table up to 17. We observed that

and that, from the Chinese Remainder Theorem, we also could infer that for

we have

Writing out a prime factorization for

we realized we’d have a formula for

if we just knew

for any prime

and any positive

We wrote out a picture and decided

We ended by proving Euler’s formula by induction on the number of distinct prime factors:

HCSSiM Workshop day 7

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

The real numbers are uncountable

Today we used Cantor’s diagonal argument to prove that the real numbers aren’t countable. Namely, we assumed they were, and that we had a bijection and then proved it didn’t contain the real number

whose

th digit we defined to be 1 if the

th digit of

is 7, and 7 otherwise. One of our students pointed out that there are some numbers that have more than one decimal expansion, so the general argument that a certain decimal expansion isn’t in the list isn’t a total proof. But we decided that we’d be able to prove on homework that the only numbers that have more than one representative in decimal expansions are rational with their denominators divisible only by 2 and 5, which is not the case for the number YP we’d been talking about.

Then we wanted to show that has the same cardinality as

We tried to use a “splicing argument” where we create a new decimal expansion out of two decimal expansions (where the odd digits correspond to the first and the even to the second), but then we decided this map isn’t well defined, since we still have this “overlap” problem where 0.999… = 1 but the pair

doesn’t get mapped by the splicing map to the same decimal expansion as the pair

So then we decided to instead consider the set of decimal expansions, which is a bit bigger than the reals, and there the splicing map works. We reduced it to this case and are leaving it to homework to prove that the set of decimal expansions has the same cardinality as the reals. Although I don’t actually know how to do this without Cantor-Schroder-Bernstein, which we haven’t proven yet.

The Chinese Remainder Theorem

We stated and proved the Chinese (Llama) Remainder Theorem. It was a nice example of a constructive proof that assumes it’s possible and then, when you follow your nose, it’s possible to completely characterize what the solution must look like, and then it falls out. We showed it described a bijection of sets We haven’t talked about homomorphisms of groups yet though so we can’t prove it’s an isomorphism of groups.

Dilworth’s Theorem on chains and anti-chains in posets

We started the proof of Dilworth’s Theorem but didn’t finish yet (to be continued tomorrow). Turns out that this problem is really hard and that, moreover, there are lots of ways to convince yourself it’s true but be wrong about. The inductive proof in wikipedia, for example, is incomplete, but can be extended to a complete proof.

As an example, try to cover the following poset on the power set of five letters with 10 chains:

In particular you can see we solve a matching problem on the way, between subsets of size two and subsets of size 3 in the set of five letters, which isn’t the normal “take the complement” match, but rather is an inclusion of one in the other. I’m still wondering if there’s a more direct way to do this.

HCSSiM Workshop day 6

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

What is a group

We talked about sets with addition laws and what that really means. We noted that associativity seems to be a common condition and that some weird operations aren’t associative. Example: define for a pair of integers

to be the sum

Then we have:

but

.

We decided those things would make them crappy generalized addition operators. We ended up by defining what a group is, although we call it a “Karafiol” so that when our final senior staff member P.J. Karafiol arrives in a couple of weeks he will already be famous.

We showed that is a Karafiol and that, if you remove all of the congruence classes with numbers that aren’t relatively prime to

you can also turn

into a group under multiplication. I was happy to hear them challenge us on whether that would be closed under multiplication. The kids proved everything, we were just mediating. They are awesome.

Graphs

We had already talked about graphs (“Visual Representations”) as defined by vertices and edges. Today we talked about being able to put vertices in different groups depending on how the edges go between groups, so we ended up talking about bipartite and tripartite graphs. We ended up being convinced that the complete bipartite graph on 6 vertices (so 3 on each side) is not planar. But we haven’t proven it yet.

Special Lecture

Saturday morning we have only two hours of normal class, instead of 4, and we have a special event for the late morning. Yesterday Johan was visiting so he talked to them about the projective plane over a finite field, and how every line has the same number of points. He talked to them a bit about his REU at Columbia and his Stacks Project and the graph of theorems t-shirt that he wore to the talk. I think it’s cool to show the students this kind of thing because they are the next generation of mathematicians and it’s great to get them into online collaborative math as soon as possible. They were impressed that the Stack Project is more than 3000 pages.

HCSSiM Workshop day 5

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

Modular arithmetic

We examined finite sets with addition laws and asked whether they were the “same”, which for now meant their addition table looked the same except for relabeling. Of course we’d need the two sets to have the same size, so we compared and

We decided they weren’t the same, but then when we did it for

and

and decided those were. We eventually decided it worked the second time because the moduli are relatively prime.

We essentially finished by proving the base case of the Chinese Remainder Theorem for two moduli, which for some ridiculous reason we are calling the Llama Remainder Theorem. Actually the reason is that one of the junior staff (Josh Vekhter) declared my lecture to be insufficiently silly (he designated himself the “Chief Silliness Officer”) and he came up with a story about a llama herder named Lou who kept track of his llamas by putting them first in groups of n and then in groups of m and in both cases only keeping track of the remaining left-over llamas. And then he died and his sons were in a fight over whether someone stole some llamas and someone had to be called in to arbitrate. Plus the answer is only well-defined up to a multiple of mn, but we decided that someone in town would have noticed if an extra mn llamas had been stolen.

Cardinality

After briefly discussing finite sets and their sizes, we defined two sets to have the same cardinality if there’s a bijection from one to the other. We showed this condition is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

Then we stopped over at the Hilbert Hotel, where a rather silly and grumpy hotel manager at first refused to let us into his hotel even though he had infinitely many rooms, because he said all his rooms were full. At first when we wanted to just add us, so a finite number of people, we simply told people to move down a few times and all was well. Then it got more complicated, when we had an infinite bus of people wanting to get into the hotel, but we solved that as well by forcing everyone to move to the hotel room number which was double their first. Then finally we figured out how to accommodate an infinite number of infinite buses.

We decided we’d proved that has the same cardinality as

itself. We generalized to

having the same cardinality as

and we decided to call sets like that “lodgeable,” since they were reminiscent of Hilbert’s Hotel.

We ended by asking whether the real numbers is lodgeable.

Complex Geometry

Here’s a motivating problem: you have an irregular hexagon inside a circle, where the alternate sides are the length of the radius. Prove the midpoints of those sides forms an equilateral triangle.

It will turn out that the circle is irrelevant, and that it’s easier to prove this if you actually Circle is entirely prove something harder.

We then explored the idea of size in the complex plane, and the operation of conjugation as reflection through the real line. Using this incredibly simple idea, plus the triangle inequality, we can prove that the polynomial

has no roots inside the unit circle.

Going back to the motivating problem. Take three arbitrary points A, B, C on the complex plane (i.e. three complex numbers), and a fourth point we will assume is at the origin. Now rotate those three points 60 degrees counterclockwise with respect to the origin – this is equivalent to multiplying the original complex numbers by Call these new points A’, B’, C’. Show that the midpoints of the three lines AB’, BC’, and CA’ form an equilateral triangle, and that this result also is sufficient to prove the motivating problem.

HCSSiM Workshop day 4

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

As usual, we started with the students showing us solutions to their problem sets. Today one of them showed a sharp lower bound on the Fibonacci numbers, although he hadn’t proved it was sharp.

Arithmetic modulo n

Then we talked more about how we can talk about addition, and now also multiplication, with a finite set of symbols . Then we wrote out the multiplication tables for

and

The students noticed and proved that there is a multiplicative inverse for

modulo

if and only if

using what we did yesterday with the Edwinian Algorithm and the way we turned it around to express gcd’s as linear combinations. We defined some notation and the natural map:

Finally, we wrote down the subsets of which map to each element of

Posets and graphs

We went back to the idea of a partial ordering, and came up with a bunch of examples (including the set of integers under “divides evenly into”). We talked for a while about how to represent partial orderings, and finally settled on a graph. We talked a bit about poset chains and antichains, and then we formally defined a graph (we voted and decided to call it a “visual representation”).

The complex plane

The founder and director of the program is David Kelly. The program has been going for 40 years now and for maybe the first time ever Kelly himself isn’t teaching a workshop, so I’ve invited him to do some guest lectures in my workshop on complex geometry. It’s always a treat to watch him teach.

Kelly came in and built on the idea of “modding out by an integer” by definine which he described as “modding out by a polynomial”. He asked the students to investigate this idea and they eventually discovered that if

it also must be true that

which allowed them to write every polynomial with as a linear combination of 1 and

so as

. Then they thought about the addition law and multiplication law and decided they had the complex plane. So we decided to start calling

the symbol “

“.

We then defined to be the point on the unit circle

discarding once and forever the notation

(we justified this definition in last night’s problem set). We showed we could recover useful trigonometric identities that way (I skipped trigonometry myself and this is the only way I ever knew how to derive those identities) and that we could alternatively write any point on the complex plane in polar coordinates, so as

. Finally, we noted that if we multiply anything by the number

, we end up stretching it by

and rotating it by

.

We heard a funny story Kelly told us about taking a test to get his pilot’s license. He was given 30 minutes and lots of suggestions once to compute a heading which involved a calculation in polar coordinates. Since he was a mathematician he was too proud to accept the props they offered him, and finished with 29 minutes to spare. Once aloft though he quickly realized his calculation simply couldn’t be correct, but fudged the test by eyeballing it and following a highway. Turns out that pilots use due north as the axis along which the angle is zero, and then they go clockwise from there. I’m not sure what the moral of the story is, but it’s something like, “don’t be arrogant unless it’s a clear day and you have a backup plan.”

Nim

Yesterday I gave a “Prime Time” talk here at HCSSiM, which is an hour long talk to the entire program. I talked about the game of Nim.

Nim is an old game (that’s the kind of in-depth historical information you’re gonna get from me) where you have a certain number of piles and each pile has a certain number of stones in it. There are two players and you take turns removing as many stones from any one pile as you want. The last person to remove a stone wins. Or, to anticipate my confusion later on, the person who gives back an empty game to their opponent wins.

You can play Nim online here with 3 or more piles and where the stones are matchsticks.

A bunch of the kids had never played so I got them to come to the board to play 2- and 3-pile Nim. Eventually it was discovered that, as long as you start out with uneven piles with 2-pile Nim, you have a winning strategy by making them even. But it wasn’t clear how to win with 3-pile Nim, so we put that question in our back pocket for later.

I then changed it up a bit and put a rook on a chessboard, and said the point was to land on the top left corner, and you could only go up and to the left. They quickly realized it was just two-pile Nim again and the winning strategy was to get the rook on the diagonal. Then I switched it up further and made it be a queen, not a rook, and allowed the piece to move up, left, and diagonally up and left. This was harder.

We then decided that, when you have a game like Nim which is two-player, and the players share the same pieces (so not chess) and moves, and when the game gets smaller every time someone makes a move, then every position can be considered either “winning” or “losing”, by growing the game up from smaller games. If you can only get to winning positions, then you’re at a losing position. If there’s an option to get to a losing position, then you’re at a winning position. A consequence of this way of thinking of things is that a “game” can be described by the options you have when given a chance to play (along with the rules that define the options).

We then discussed adding two games A and B, which just means you get to play from either A or B but not both. We decided that 2-pile Nim is already of the form A + A, where A is 1-pile Nim. And furthermore, 1-pile Nim is pretty dumb – the winning strategy is always to just take away all the stones. But in spite of this, 5 stones is not the same as 6 stones for 1-pile Nim, since you can get to 5 stones from 6 but not vice versa.

Then I defined A ~ B if for all other (impartial) games H, A + H always has the same winner as B + H. It’s easy to see ~ is an equivalence relation, and that G + G is always winning (again, by mimicking your opponent’s moves). It’s also pretty easy to see that if A is winning, then A + G ~ G for all G.

But it’s a bad definition of ~ in that it seems to take an infinite amount of work to decide if A ~ B, since you’d have to check something for all possible H. We decided to improve this by proving that G ~ G’ if and only if G + G’ is winning. It is pretty easy to do this.

Then it was time for action, namely to prove the Sprague-Grundy Theorem which states that:

Every impartial game G has G ~ [N] for some N, where [N] denotes 1-pile Nim with N stones.

We prove this by showing recursively on the size of the game that N above (also called the “Nimber” of the position) is just the “mex” function, which is the minimum excluded non-negative integer. In other words, we designate the winning position as having N = 0, and then we grow the game up from there. If a given position can get to a “0” position, then its Nimber is at least 0 – in fact it’s the minimum number that it can’t reach in one move.

In particular, if you are at a position with Nim number non-zero, you can get to a zero position (i.e. a winning position), as well as any smaller Nim position, and if you are at a position with Nim number zero, you can only get to non-zero positions. This is similar to the losing-winning dichotomy except slightly more nuanced.

We then drew a Nimber addition table, which is the same as the chessboard problem with a rook. We used this to reduce 3-pile Nim to 2-pile Nim and worked out a winning strategy for the 3-pile Nim game (2, 5, 3).

Next we drew a Nimber table for the queen on a chessboard problem. We decided we knew how to play that game plus a 3-pile Nim game.

I was running out of time by this time but I ended with showing them a fast way to find the Nimber of the sum of a bunch of games whose Nimbers you already know, namely the bitwise XOR function. I didn’t have time to prove it (it’s not hard to see with induction on the number of games you’re adding up) but it’s easy to see this recovers our “mimicking” strategy with two games.

HCSSiM Workshop day 3

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

Equivalence Relations and Partial Orderings

After going over many proofs of the geometry problem from last night’s problem set, I corrected the mistake in the “antisymmetric” property and we went through plenty of examples of equivalence relations and partial orderings. We ended with linear orderings, the real numbers, and the less than or equal relation.

Adding modulo n

Next we went back to the idea of maps and got the kids to come up with a whole bunch of examples for

such as

. We eventually got them to come up with stupider examples like

and

Then we switched it up to the finite set

and got them to generalize addition. Since

really started to look like an identity element under this operation, we decided to define notation for the set

which is like

but on its side.

Pigs-in-hole Principle

We introduced the pigeonhole principle (but since our camp mascot is a yellow, pig, we call it pigs-in-hole). We actually defined the slightly more general idea that, if you have holes and

pigs which need to get put into holes, at least one of the

holes to contain at least

pigs. With that we proved that at least 2 people in New York City have the same number of hairs on their head, that five points in a 1 by 1 square are withing distance

of each other, that in a group of $n$ people at least two people will have had the same number of handshakes, and others.

Greatest Common Divisor

We asked the kids what the greatest common divisor of and

is (denoted

) and how to compute it. We spent a long time chasing down rabbit holes and proving other things that didn’t help us find the greatest common divisor but were true. For example, we showed that if you divide

and

by their greatest common divisor, you end up with numbers that are relatively prime. We even showed there are representations of

and

as products of primes, but since we couldn’t yet prove those were unique representations, we could use that to come up with a way to find the “common primes.”

Eventually we thought of a trick to reduce the problem, namely the division algorithm. Actually Edwin thought of the trick, and it eventually became the Edwinian Algorithm (not like it’s usually called, namely the Euclidean Algorithm). Edwin observed that when you write

for

Once we had the Edwinian Algorithm, we realized we could go backwards and express as a linear combination of

and

, and we used that to prove a very important property of primes, namely that if

is a prime and

then either

or

or both. This allowed us to show that the prime factorizations we’d found before for

and

were in fact unique up to relabeling, which we left for homework.

So it turns out I’m not going to be able to make the homeworks public, but we had an awesome problem set with lots of pigeon hole problems and Edwinian Algorithm problems. We asked them to decide which approach to calculating is faster, through the Edwinian Algorithm or via prime factorizations.

HCSSiM Workshop day 2

A continuation of this, where I take notes on my workshop at HCSSiM.

The watermelon cutting problem revisited

We prove that the maximum number of pieces of watermelon you can cut with slices, assuming a watermelon of dimension

, denoted by

is given by:

First we proved it with a combinatorial argument, then with induction. I decided the first one is better because you figure out the answer as you go, whereas the induction route requires that you already know the formula. They both require you to use the recursion relation we talked about yesterday, and the first one involved writing a 2-d chart and showing how to unpack the value of using the recurrence relation, into paths going up to the top row consisting of all ones, and then the question becomes, “how many ways can you get to the top row?” and of course the answer is something like

, where you go up

times and left

times.

All pigs are yellow

Next we proved, using induction, that all pigs are the same color, and then we exhibited a yellow pig so a corollary was that all pigs are yellow. The base case is that a single pig is the same color as itself, and then assuming we have n pigs of the same color, we get to the statement that n+1 pigs are all the same color by first putting one pig in the barn, and then some other pig in the barn, and the leftover pigs are the same color as each of those so they’re all the same color.

This argument, of course, doesn’t work when you’re moving from “1 pig” to “2 pigs” and exhibits how careful you have to be with working through enough base cases so that your inductive step actually applies.

Strong Induction

We then went to using the Principle of Strong Induction (after showing that there’s no Principle of Induction over the real numbers). We proved that all numbers can be written as the sum of powers of 2, that the Fibonacci numbers grow exponentially, that every positive integer at least 2 is divisible by a prime, and that every planar polygon can be diagonalized using strong induction.

Notation

Incidentally, instead of “Strong Induction” the students voted to call it “Thor Induction”, and instead of the standard end-of-proof symbol, which is a box with an “x” inside, we voted to use the symbol “(see next page)”. They had lots of fun with that one. As a corollary, they decided that if they wanted someone to actually see the next page, they’d use the “Q.E.D.” symbol.

Cross product of Sets

Finally, we talked about the notation which denotes the cross product of sets, and made a bunch of examples, mostly of the form

specifically when

and

which we then drew as the plane and the lattice points. We ended by showing an injection from

into the lattice points, which incidentally showed that

and

have the same cardinality, which we didn’t really define but we will.

HCSSiM workshop day 1

So I’ve decided to try to explain what we’re doing in class here at mathcamp. This is both for your benefit and mine, since this way I won’t have to find my notes next time I do this.

Notetakers

We started the math, after intros, by assigning note-takers. In one row we wrote down the students’ names (14 of them), and in the other we wrote down the numbers 1 through 14. We drew lines from names down to numbers. These were the assigments for the days they’d take notes.

But to make it more interesting, we added pipes between different vertical lines. The pipes can be curly (my favorite ones were loopedy-loop) but have to start at one vertical line and end at another at “T” crosses.

Then the algorithm to get from a name to a number was this: start at the name, go down the vertical line til you hit a “T”, follow the “T” pipe til you hit another vertical line, and then go down.

This ends up matching people with numbers in a one-to-one fashion, but why? We promised to prove this by the end of the workshop.

Map of Math

We next had the kids talk about what “math” is. We had them throw up terms and we drew a collage on the board with everything they said. We circled the topics and connected them with lines if we could make the case they were related fields. We drew lines from the terms to the topics that used that a lot – like the symbol got pointed at Trigonometry and Geometry, for example. I think it was useful. Lots of terms were clarified or at least people got told they would learn stuff about it in the next few weeks.

Cutting Watermelons

Next, we asked the kids how many pieces you can cut a watermelon into with 17 cuts. Imagine the watermelon plays nice and stays the shape of a watermelon as you continue cuts, and you can’t rearrange the watermelon’s pieces either.

If you do a few cuts it quickly gets hard to imagine.

So go down to a 2-dimensional watermelon, which could be called a pizza or a flattermelon. We called it a flattermelon. In this case you’re trying to see how many pieces you can achieve with 17 cuts. But also you may notice that a single slice of a 3-d watermelon looks, to the knife’s edge, like you are spanning a flattermelon.

Similarly, you may notice that a cut of the flattermelon looks like a 1-dimensional watermelon, otherwise known as a flatterermelon. And there the problem is easy: if you have a one dimensional watermelon, i.e. a line, then n cuts gives you maximum n+1 pieces. But going back to a pizza a.k.a. flattermelon, any cut looks from the point of view of the knife like a 1-d watermelon, which is to say it is cutting n+1 regions into half assuming the lines are in general position. So we get a recursion. If we denote by the max number of pieces you can get in

dimensions with

cuts, then we can see that

Since we know this recursion relation generates everything, although not in closed form.

Notation

Next, I went on at length about the utility and frustration of notation. Namely, notation is only useful if everyone agrees on what it means. I like standard notation because it’s more, well, useful, but Hampshire is a place where kids absolutely adore making up their own notation. As long as we are consistent it’s ok with me, and I like the fact that they own it. So instead of the standard notation for “n choose k” we are using a pacman symbol with n inside the pacman and k being eaten by the pacman. We call it “n chews k”.

Combinatorial Argument

We talked about putting balls in baskets, and defined that pacman figure to be the number of ways we can do it. Then we proved the pascal’s triangle recursion relation using the argument where you isolate one basket and talk about the two cases, one where there’s a ball inside it and the other when there’s not. Then we identified Pascal’s triangle as being equivalent to this concept of counting. I described this as an example of a combinatorial argument, which I like because it doesn’t involve formulas and I’m lazy.

Induction

Finally, I introduced Mathematical Induction and did the standard first proof, namely to show the sum of the first n positive integers is

Free online classes: the next thing

I love the idea of learning stuff online, especially if it’s free.

So there’s this place called Code Academy. They teach you how to code, online, for free. They crowdsource both the content and the students. So far they focus on stuff to build websites, so javascript, html, and css.

I just found out about Udacity (hat tip Jacques Richer), which also seems pretty cool. They offer various classes online, also free unless you want an official certificate saying you finished the class. And they have 11 courses so far, including this one on basic statistics with Professor Thrun.

Then there’s Coursera, which is starting to have quite a few different options for free online classes. The thing I’d like to bitch about with this is that Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning class, which I took when it came out last year, is not being offered currently, which makes me confused. Why does it need scheduling if it’s already been made?

I also just discovered openculture, which lists lots of free online courses. When you search for “statistics,” it returns the Udacity course I already mentioned as well as a Berkeley stats course on YouTube, among others.

I know this stuff is the future, so I’m hoping there continues to be lots of competition from various small start-ups. We are bound to profit from such competition as a culture. What I’m worried about is that the model goes from “free” to “fee” if it gets crowded by large players who, say, pay their instructors a lot for the content.

Which is not to say the instructors shouldn’t get paid at all, but I hope the revenue can continue to come from advertising or through job matching.

Google’s promotion policy sucks for women

I’m going to start this post with an excerpt from a comment of reader JoanDelilah from a couple of weeks ago, commenting on my post The meritocracy myth:

And at the end of the day, this also assumes that it is right and proper for a structure to be in place which requires you to *grab* tough/interesting work to prove yourself, as opposed to it being given to you. There is competition inherent in the foundational world-view behind that statement. Why so much competition? We are supposed to be on the same team and competing with other businesses, right? What about the woman who is happy to crush any assignment she is given but simply doesn’t want to have to compete for the assignments that will “prove” her abilities? Why must she step so far out of her comfort zone just in order for the company that pays her to make use of the talents they are paying her to use?

This really nails down what I see all the time with respect to women getting promoted or even just getting recognized for their achievements.

To paraphrase it, women tend not to compete for recognition as much as men, for whatever reason. Maybe they’ve been socialized not to, maybe it is a simple question of testosterone. I will go into why I think this happens below. But for now let me just say I get super pissed when a system has been set up to diminish the success of people simply because of this personality issue.

Google is one such system. At Google, one must self-promote. I believe the rule is that, after two quarters or so of getting good reviews, you are eligible to self-promote, but you don’t have to.

And guess what? That policy sucks for women. Women don’t do it as often. I’ll bet this is statistically significant, even though I don’t have the numbers. Hey Google, do the math on this policy! And then change it!

Here’s the first part of my theory of why this happens. Women are not as secure in their accomplishments. By the way, note I am not saying women are insecure and men are secure. I think it’s more like men are over-secure and women are realistic, kind of like those studies that shows that depressed people are realists and non-depressed people are optimists. I definitely have seen men who actually think they (individually) accomplished something which clearly took a team effort. Women are less likely to “forget” the help they received in making something happen. See this amazing blog rant on the subject from a professor at NYU.

Here’s the second part. Women tend to choose mentors (i.e. bosses or advisors) that are brilliant, thoughtful, and approachable. Typically this also means that those mentors are not the kind of bullying personalities that are best suited to promote their team. Even when one doesn’t have a choice in who your boss is, I claim this approach to pairing still happens in a business when that business decides who should be the boss of a woman.

Example in pure math: Yau at Harvard is famously dynasty-building with his students, but he’s probably not someone who has a tissue box in his office (to be fair I haven’t checked). I didn’t even consider taking Yau as my advisor, in part because he was super intimidating and seemed to challenge grad students with a ring of fire.

The reward for being brave in a situation like that are that he is fiercely loyal to his students once he accepts them, and helps them get great jobs. My point is that fewer women choose Yau-like personalities as their advisor (although it has to be said that Yau has had women students, including Columbia’s Melissa Liu). And thus fewer women end up with advisors that will land them jobs and give them good advice on how to get ahead. I just don’t think women are thinking about that aspect of a mentor the way men do (it’s also possible than men don’t think about it either but are less likely to shy away from rings of fire in general due to their “optimistic” egos).

I am not saying this is an easy problem to fix, because it’s not, and the best self-promoters will always do well no matter where they work. But I do think Google can do better than this; maybe they could think of something a bit more double-blind like the orchestra auditions.