Archive

It’s time to stop watching football

My husband and I have boycotted football. It’s hard, especially at this time of year when baseball is winding down, and our traditional Sunday and Monday night activities involve beer and relaxation while watching bunches of men in tight jumping on other bunches of men in tights (although the Mets being in the World Series certainly helps for now). I’ve been a football fan for more than 20 years, so it’s a deeply held habit.

Nowadays, though, every time I hear the familiar crunch of football helmets crashing against each other on the front lines or the receivers being thrown to the ground, all I can think is “concussion.” And it’s more than just one concussion, or even a few. It’s known to accumulate and lead to a serious and debilitating brain disease, called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. Memory loss, dementia, that kind of thing, at young ages. Here’s a wiki page listing the players who are known to have CTE and who are involved in a lawsuit against the NFL for concussion-related injuries. The lists are far from complete. In fact, a recent study showed that 96% of deceased players suffered from CTE. So a good approximation of a complete list would be “all football players, ever.” Acute readers have pointed out that the group studied in this paper were self-selected, so there’s likely a bias involved. Even so, nobody would argue that football isn’t rife with CTE.

Here’s the thing. I have three sons, and I wouldn’t let any of them play football. So what does it mean that I let myself be entertained by other people playing it?

It’s similar with the military. I would absolutely avoid my sons entering the military if possible, because of the inherent danger. It’s an extremely privileged position to take, because I’m not claiming the U.S. shouldn’t have armed forces, but I would still act to prevent my kids from being involved, at least as it is now.

On the other hand, I am also fully aware that one reason we enter wars the way we do is that the children of the privileged are by and large not on the front lines. In other words, I am willing to engage in a conversation about what kind of army we would need to have, and what kind of military engagements we would enter, if everyone were a soldier for at least a little while, including women. In principle, it would be a better system. We would all have a serious stake in making it better.

Football is different, of course. Nobody needs to play football. That means I don’t need to consider sending my son, and other sons, off to training camp in order to have skin in the game. If the past few years of child abuse, wife abuse, and violent and criminal tendencies leaking out of NFL and college football locker rooms haven’t convinced us we need to clean that up, then I don’t know what would.

The analogy of the army and football is apt, however, in some ways. One of the most uneasy aspects of my enjoyment of football has always been the way the NFL and even college football coaches and media play up and play to the military aspects of the game. They talk about war, they talk about preparing for battle, they discuss the shame of losing a game as if it involved lives lost. They perform weirdly contrived rituals when there is military presence in the audience. It makes you think of the worst kinds of forced patriotism. Rudy Giuliani-ism, if you will. It’s not earnest.

And it’s too much. Last Saturday night I was having trouble sleeping so I listened to sports radio, which is what I do. Much of the coverage centered on the dismal performance of a Miami college football team in a 58-0 loss. If you didn’t know what they were talking about, the words they were using, and the coach’s interview, sounded like the end of the world. If I had been a player on that team, I might have considered suicide, it was so bad.

What the fuck is wrong with us? Why do we take these games so seriously? Especially when young people are concerned, it makes no sense. And I’m saying that as a huge sports fan: we need to realize this stuff is just a game. We need to enjoy the victories and ignore the defeats. And crucially, we need to treat college level sports like we treat minor league baseball, namely not that important because it’s young kids learning to play the game.

I’ve lost patience with the violence of it all. Kids are losing their lives from injuries, and better helmets aren’t going to fix this problem. The NFL is avoiding dealing with the problem, because there’s so much frigging money on the table. Instead they shove yet more military might talk and fake patriotism down our throats, hoping we won’t think too hard about it between rounds of beer.

So I’ve been boycotting football this season. I have meant to do it for a few years, but this season it’s finally stuck. That doesn’t mean I don’t encounter football by accident. In fact it happens all the time, because it’s everywhere. Just the other day I was at a bar with some friends and I went to order a beer, and looked up at the TV, and there it was, Sunday night football. The play had been suspended because a player was lying unconscious on the field. Another head injury.

In Praise of Cabbies

My son’s tibia (shin) bone was broken last Thursday, after school, in a totally random soccer accident (shin against shin). That has resulted in four excruciating days of pain for him, though thankfully each less bad than the last. Even after your leg is in a cast, any kind of micro-movement that vibrates a broken tibia even in the slightest gives you pain. So getting into or out of bed, going to the bathroom, or god forbid getting into a cab, is very slow and often very traumatic.

He’s had to get into and out of 4 cabs since it happened. After the first, we figured out that carefully pulling him backwards, across the seat, while someone else hold his leg as still as possible, is the best approach. It hurts, of course, but not as badly as other systems.

Three out of these four times that we did this, the cabbies were infinitely patient and kind. They had no problem waiting, for as long as it would take, and they even offered to help. I was so grateful, because obviously it’s not good money to be waiting around for a crying 7-year-old to calm down and move one more inch.

But for one trip, to get the permanent cast put on at Mount Sinai, I had to miss the cab trip in order to be downtown for my Slate podcast, and my husband went without me. The cabbie volunteered to help, and as Johan put it, he was “infinitely strong and infinitely patient” and somehow managed to port my son backwards across the back seat in a perfect, smooth motion, that made him think he was levitating. It was the least painful of all the journeys.

Can I just take a moment now, and mention how grateful I am to all of these guys? These four cab drivers were all extremely kind and sympathetic men, any of whom would have immediately done whatever they could to help my son. And here’s the thing, I don’t even think I was particularly lucky; I think that’s actually pretty normal for cabbies. They are some really great people, willing and able to help out strangers all the time. That’s their job. And in a big, crowded city that might seem anonymous and pitiless, it’s a super comforting feeling to know they are there.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Readers, Aunt Pythia is a bit sad and a pinch exhausted today. On Thursday, Aunt Pythia’s sweetiepie 7-year-old had an accident at school and broke his tibia bone. And it really caused him such excruciating pain, readers, that it was terrible to behold. You all would have been crying alongside Aunt Pythia if you’d been there.

Now he’s got a good cast on, thank goodness, and a waterproof one at that, which means he can take showers and even baths with it, and things are normalizing, but it isn’t great, and bathroom visits are a real ordeal.

The moral of that story is, thank goodness for casts.

You can even swim with it. The water goes in but then drips out.(this is not a picture of my 7-year-old)

For that matter, can we take a moment to just appreciate penicillin too? And our present-day understanding of hygiene? And surgical techniques and such? That stuff is amazing, and I’m glad I’m alive today to enjoy it all. Who’s with me?

After meditating on modern medicine, and digesting the questionable content below, please don’t forget to:

ask Aunt Pythia any question at all at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I need your help! I am a (relatively) young womanly person of late 20’s who is striving to become more conscientious about where to ethically invest my earnings. When researching how much I need to have prepared for retirement, all of the online calculators and financial advisers I’ve consulted have thrown a figure my way in the ballpark of $2-3 million assuming a retirement age of mid to late 60s and a 4% gradually increasing annual withdrawal rate.

While I make a decent income (70K), there is not much of a chance that I can save that much in the next 35 years without falling into the trappings of Wall Street investment returns. I can’t do much about the restrictions my employer has placed on my 401K investment options, but I do have control over my IRA and general savings/investment practices.

What micro-level advice do you have for people starting out in ethical retirement planning/investing? Any resources or must reads? Much obliged.

Confused And Tentative

Dear Confused,

First, let me just say that you are way ahead of your peers in planning this stuff. I really haven’t started planning myself, because kids cost so much and so on, and I’m figuring I’ll just work until I die.

Second, there’s really no way every person can have $2-3 million in retirement savings. I just don’t think it’s reasonable or realistic. Think about that as a social policy: hey everyone, I know you’re still paying off your student loans, and that the cost of renting is sky high, and homes are already overpriced and poised not to rise, and daycare costs more than ever, but please save $2 million on top of everything else. WTF.

Not a viable expectation for the average household. Politically speaking, retirement in this country is going to have to change as the post-Boomer population gets old and continues to be broke.

Also, you’re right, there are few options for ethical investing that aren’t risky. I mean by that that you can always sponsor your friend’s ethical business, but most businesses fail, so it is super risky. More generally, if you’re interested in avoiding fossil fuel investments, take a look at this, and if that catches your fancy, check out this website.

But my general advice is to do your best, and stay healthy, and not worry too much about money. If you have retirement investments, great, and think of putting some in an ETF that tracks the market just as a hedge against political manipulation more than anything else.

Good luck,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I love your column. It feels like a community of warm hugs. I have gone back and forth on sending this embarrassing question so many times, but I finally decided that I need your honest insight.

As a minority grad student in STEM, I routinely come across mean, patronizing jerks. I have learnt to survive my interactions with them with my sanity somewhat intact. However, what catches me off guard is my reaction when someone decides to take an interest in me and mentor me academically and personally. I end up developing a crush almost every time.

I want to make it very clear that I don’t want a physical connection with them at all. But, I do fantasize about an emotional and intellectual bond with them. Some of these relationships have actually led to some wonderful (strictly platonic) mentoring relationships.

Grad school and academia can be very isolating, so it’s so nice to have someone to talk. And if this someone has been in your field doing the work that you dream of doing one day, that’s even better. Still, I can’t help feeling guilty for feeling so vulnerable that even the slightest bit of attention or praise from them makes me feel so exhilarated.

I have friends outside of my field and am a somewhat social person with a fairly fulfilling personal life. So, what is it about charming, passionate, and kind STEM people that brings out these intense feelings in me? How do I avoid developing these silly crushes?

Lastly, (I’m not even sure that I am prepared to hear an honest answer to this), do you think my feelings are obvious to them? I am always respectful and deferential to them, but I wonder if they might have an inkling anyway. I love what I do and I don’t want my work to be undermined by these stupid feelings that I can’t seem to be able to control right now.

Great Regrets About Pining Heart

——

Dear Pining,

Oh my god, I am so glad you wrote. I am the same way. Seriously. And the crushes can be quite intense, sometimes, right? I remember when one of my sons (I won’t name his name because he’ll hate me for it) went through his first crush when he was about 6 and he said to me, “I love her so so much, it’s getting worser and worser!” and he looked positively anxious about what would happen to the explosion happening in his little heart. Well, I got him at that moment, and I get you now.

But wait, and here comes what will become my tag line, what’s the problem here? You haven’t actually told me why this is a bad thing except for how you sometimes get embarrassed by them.

To answer your question: do people notice your crushes? Maybe, probably not in an exact way, but even if they did it would be super flattering. And since it’s platonic, and you’re looking for an emotional bond, I’m thinking that’s exactly appropriate, and probably also what they want.

Finally, I’d say you are controlling yourself with respect to these feelings, in spite of your sense that you’re not. In other words, you can’t control your feelings directly, but you can control what you do in response to them. And since you haven’t actually done anything super impulsive, and stuff hasn’t developed beyond intellectual and emotional realm, I am not only proud to say I get you, I’m proud to say you’ve done great.

You know what? I feel sorry for people who aren’t like us, and for whom it takes weeks if not years to develop strong emotions for people and things. They don’t get to experience the intensities that we do! And yes, it means they spend less time lying on couches crying about broken hearts to dear friends who have heard it all before many times, but whatever, we always eventually pick ourselves up again and go find a new person to love. Plus we buy our friends beer and they merrily forgive us.

Many warm hugs,

Aunt Pythia

p.s. there really is no way to avoid this, it’s part of you, like your arm. I’ve tried. Just buckle up and try to enjoy the ride.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m in my early thirties. I have a newborn, my first child, and I find it so damn hard to take care of him. He’s now 8 weeks old, and I’m on maternity leave for 6 months (luckily I’m in Europe, can’t imagine what I would have done in the States).

Both my husband and me live abroad and have no family around to help. I consider myself a pretty capable person, and I keep thinking how the hell do other people manage. There are so many babies, children, people in this world. How do all millions of moms manage, when I’m barely surviving?

I have figured out how to be highly successful academically and professionally. I have learned to have good relationships and a pretty good life. But I am probably average at taking care of a newborn. I find it so hard.

Dear Aunt Pythia, did you have a hard time too when you had your first baby (and second and third)? What helped? Any tips? Ideas? Strategies? What would you do differently if you had your first one again?

Maybe Overthinking Motherhood

Dear MOM,

Thanks for asking. I tell this to everyone I know with a newborn, especially if it’s their second.

Namely, the first 4 months of a baby’s life, and especially the first 6 weeks, is really really hard. In fact the way to survive it is to try to quantify how difficult yesterday was, and compare it to today, and take note of the minute differences. Give yourself a break, and a chance to cry, every time there’s been a regression, and give yourself a party every time there’s even the smallest amount of progress. In other words, keep your head down, in a day-to-day sense, and you will slowly begin to see how certain things have gotten easier (breastfeeding, putting them down to nap, walking around without pain) even as other stuff is momentarily harder (sleep deprivation, never getting a chance to take a shower, running out of groceries). It’s super painful, and surprisingly difficult, but after a few weeks you begin to see things improving, and then by the time they’re 6 months old, you almost feel human again.

Oh, and the moment they try to keep themselves up to say up with you when they’re tired is the moment when you can train them to sleep through the night. This usually happens at 5 months or so. And the trick there is, if you notice a bunch of fussing with an 8pm bedtime, then put the baby down at 7:30 the next night. And if they’re fussy at 7:30, try for 7pm the next night. Sounds counter-intuitive but it works.

Finally, the only moment where I really felt truly desperate was when I had a newborn and a 2-year-old and my husband went away for a math conference for a week, and I was working. Please kill me now, I thought, and I meant it. But even that ended, and now those two kids are like, almost adults, and they are my favorite people to hang out with. The younger one just explained fission to me the other day.

In the words of my wise mother, sometimes you just have to muddle through. Also, good babysitting is worth it. Go into debt temporarily if necessary, it’s still cheaper than therapy.

Hugs,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I want to fuck an aunt.

Manoj

Dear Manoj,

Thanks for the note. It reminds me that, as a WordPress Premium member, I get to look at all kinds of statistics with respect to how people got to my blog, what they looked at and when, and which links they click on while they’re here. It’s interesting, and I look at such statistics daily.

One of the categories is a list of search terms that people used to get to my blog, and by far one of the most common ones has been, over the years, something about aunts and sex, so a kind of incest fetish thing. For example, here’s a screenshot of today’s search terms:

So, what can I say? Aunt Pythia constitutes – possibly defines – her own bizarre porn fetish category. It’s somewhere in between flattering and repulsive.

So Manoj: thanks, I think.

Aunt Pythia

——

Readers? Aunt Pythia loves you so much. She wants to hear from you – she needs to hear from you – and then tell you what for in a most indulgent way. Will you help her do that?

Please, pleeeeease ask her a question. She will take it seriously and answer it if she can.

Click here for a form for later or just do it now:

The internet is no place for conversation

I admit I’m lucky. On a daily basis I think to myself, “damn my commenters are smart, and thoughtful, and they make me think and rethink my positions.” That’s amazing! I love you people!

But it’s really not like that in general. The crazy, outsized responses and reactions to responses you find on almost any unmoderated discussion are just… terrible.

Case in point: a few people yesterday – including some wonderful commenters! – pointed me to this Atlantic article on calculating the chances that a 20 person panel at a math conference would contain only one woman.

[As an aside: the assumption was that the pool of possible panelists was 24% female, since 24% of recent Ph.D.s are women, and the probability mass function from a binomial distribution was used, which is reasonable. What’s possibly controversial is the assumption that every person who has a Ph.D. is equally qualified and available to be on a panel. The reasons they aren’t are interesting and complicated, and what’s important is that we understand it, not that we put all the blame on people who organize panels. Although people who organize panels should obviously try to do better than 1 female panelist out of 20.]

Well, take a look at the comments from this article. The very first comment contains this:

Of course panels like this will be dominated by men. If the women had a panel, most of them would want to talk about volunteering at– you got it– the local PTA.

And – guess what? – the conversation doesn’t get better after that. It’s such a shame, and such a wasted opportunity. Only people willing to resort to very low level, hostile accusations are willing to wade into that muck.

I’m just not sure what can be done about this. Do we turn off comments? Do we turn off comments except for moderated comment sections, like the New York Times? That’s very expensive. Do we devise algorithms that try to detect hateful or hostile speech and put that stuff in a harder-to-reach area? To some that stinks of censorship, but on the other hand those people often have a weak understanding of freedom of speech. Here’s a good explanation.

I guess the question is, what do we owe to the idea that everyone gets their say, and what do we owe to the idea that we want to have an actual meaningful conversation?

Personally, I moderate the first comment someone suggests, and once they’re in, they’re in. It doesn’t always work – sometimes I have to delete further comments by someone, if they become disrespectful – but it mostly does. And it really only works because on a given day I get a dozen or so comments. I wouldn’t be able to do it for a large site. Even so, I’ve really appreciated the resulting conversation.

Minority homeownership and wealth-creation

I don’t think it makes a ton of sense to invest in houses right now. They’re overpriced in many areas, they pose much more risk as a homeowner than as a renter – assuming the renter laws are locally strong – and there’s no reason to believe their value will increase faster than inflation in the next few years or decades. When the topic comes up, I urge people to rent.

But it’s hard to say that to people, and minorities in particular, when homeownership is taken as a large part of the American Dream, and especially when the recent financial crisis has been so brutal with respect to black homeownership. Because when someone says “don’t buy a house,” what black people might hear is that only white people will ever own homes in this country, and that is somehow the way things should be. But of course that’s not the point, nor is it the starting point of this discussion.

First, we should remember that historically, the government propped up the mortgage market and deeply inflated housing prices first by giving a tax deduction for mortgage payments and second by creating Fannie and Freddie, which established the existence and (relatively) easy attainability of the 30-year mortgage for many, and moreover kept liquidity high, which eventually led to mortgage-back securities, yadda yadda yadda. But the point is this: the easier it is to get financing, the higher prices get. Look at college tuition. The cheaper the monthly payments are, moreover, the higher prices get.

At the same time, government and government-sanctioned policies kept minorities away from buying good houses and obtaining good mortgages in the post- WWII era, which was by far the best time to buy a house. Then homes just kept getting more and more expensive until the financial crisis.

In other words, homes were set up, by the government, to be a good investment about 50 or 60 years ago. That doesn’t mean they are a good investment now. In fact I don’t think they are. But in the meantime, black people were prevented by and large from taking part in this wealth creation, which is absolutely shameful, but it doesn’t mean that they should now be pushed into buying homes in some vain attempt to get a piece of the wealth-creation action. It’s not only historical, either: even now, wealthy minority neighborhoods have less home value per dollar of income than wealthy white neighborhoods.

Part of the confusion around homes and owning a home is the very definition of homeownership. People seem to think they own a home when they’ve signed a mortgage. But, given that down payments can be small, as little as 3%, the difference between having some cash in a savings account and “owning a home” is small, and not especially in favor of the “homeowner.” It simply means you’ve signed a contract putting you on the spot if the roof leaks, if the basement gets flooded with water or oil, or if the housing market dips. It’s true that you get to live in the house, which is a great and useful thing, but you also get to live in a rented house, and you don’t take on all of those risks.

Let me put it this way. If you bought a pie and only had 3% of the money for it, you wouldn’t really think it was your pie, because your slice is extremely small. Plus if a dog came and ate up the pie, you’d be responsible for rebuilding the pie. It is a lot of responsibility and very little in the way of benefit.

A mortgage is basically a highly leveraged and risky financial instrument for the homeowner. And where before the government could be counted on to allay much of the risk through policy, they’ve run out of way to do that. Or, put it another way: what would the US government have to do to make houses even more expensive. given the affordability crisis we now have? And what’s the likelihood they’ll do that?

There’s one good thing, potentially, about entering a mortgage contract for anyone who does it, namely forced savings. If you’re lucky enough that your roof doesn’t leak too often and your basement doesn’t get flooded too often, and if you got a non-predatory mortgage that you can afford to pay in perpetuity given your salary, so it doesn’t matter too much when the housing market dips, and if you don’t lose your job, then mortgage payments – eventually – start going to principal, and you end up saving money for real, as long as the dips aren’t too bad, and that’s a good thing (as long as you don’t refinance with new mortgages that take money out of your house). But that’s a lot of ifs.

Instead of focusing exclusively on homes, I’d like us to move on and think of other ways to help people save money. Of course this starts with them making enough money to have extra to save.

Guest post: Dirty Rant About The Human Brain Project

This is a guest post by a neuroscientist who may or may not be a graduate student somewhere in Massachusetts.

You asked me about the Human Brain Project. Well, there is only one way to properly address that topic: with a rant.

Henry Markram at EPFL in Switzerland was the leader of the “Blue Brain” project, to simulate a brain (well, actually just one cubic millimeter of a mouse brain) on an IBM Blue-Gene supercomputer. He got tons of money for this project, including the IBM supercomputer for the simulations. Of course he never published anything showing that these simulations lead to any understanding of brain function whatsoever. But he did create a team of graphics professionals to make cool pictures of the simulations. Building on this “success”, he led the “Human Brain” EU flagship project into being funded by some miracle of bureaucratic gullibility. The clearly promised goal was simulating a human brain (hence the name of the project). Almost everyone in Europe publicly supported the project, although in private the neuroscientists (who, if they have done any simulations, know that the stated goal is completely absurd) would say something more like “hey, maybe it’s crazy, but it’ll bring a bunch of money.”

Now, some simple observations must be made, which are true now, and will still be true in ten years’ time, at the conclusion of this flagship project:

(1) We have no fucking clue how to simulate a brain.

We can’t simulate the brain of C. Elegans, a very well studied roundworm (first animal to have its genome sequenced) in which every animal has exactly the same 302-neuron brain (out of 959 total cells) and we know the wiring diagram and we have tons of data on how the animal behaves, including how it behaves if you kill this neuron or that neuron. Pretty much whatever data you want, we can generate it. And yet we don’t know how this brain works. Simply put, data does not equal understanding. You might see a talk in which someone argues for some theory for a subnetwork of 6 or 8 neurons in this animal. Our state of understanding is that bad.

(2) We have no fucking clue how to wire up a brain.

Ok, we do have a macroscopic clue, this region connects to that region and so on. You can get beautiful pictures with methods like DTI, with a resolution of one cubic millimeter per voxel. Very detailed, right? Well, apart from DTI being a noisy and controversial method to begin with, remember that one cubic millimeter of brain required a supercomputer to simulate it (not worrying here about how worthless that “simulation” was), so any map with cubic-millimeter voxels is a very coarse map indeed. And microscopically, we have no clue. It looks pretty random. We collect statistics (with great difficulty), and do tons of measurements (also with great difficulty), but not on humans. Even for well studied animals such as cats, rats, and mice, it’s anyone’s guess what the fine structure of the connectivity matrix is. As an overly simplistic comparison, imagine taking statistics on the connectivity of transistors in a Pentium chip and then trying to make your own chip based on those statistics. There’s just no way it’s gonna work.

(3) We have no fucking clue what makes human brains work so well.

Humans (and great apes and whales and elephants and dolphins and a few other animals that we love) happen to have a class of neurons (“spindle neurons”) that we don’t see in the animals that we spend most of our time studying. Is it important? Who knows. We know for sure that we are missing a lot about what makes a human brain human — it’s definitely not just its size. There’s a guy whose brain is mostly not there, and he was probably one of the dumber kids in class, but still he functions fine in human society (has a job, family, etc.). Is this surprising? Not surprising? How would we know, we don’t know how brains work anyway.

(4) We have no fucking clue what the parameters are.

If you try to do a simulation to see how neurons behave when they are connected in networks, you need to know a bunch of biophysical parameters. For example, what’s the time constant for voltage leak across the cell membrane? And a ton of other parameters, which are of course different for different classes of cells. So let’s just take the most common excitatory cell class and the most common inhibitory cell class and try to make a network. Luckily, there are papers that report numbers for this or that parameter of these cells. But the reported numbers are all over the place! One lengthy detailed study will find a parameter to be 35±4, and the next in-depth study will find the same parameter to be 12±3. So what should you use in your simulation for this or the many, many other uncertain parameters? Who the fuck knows.

(5) We have no fucking clue what the important thing to simulate is.

Neurons in vertebrates communicate (*) via “spikes”, where the neuron’s voltage level suddenly goes way up for a millisecond or so. This electro-chemical process, involving various ions flowing across the cell membrane, is very well understood. But now, what do these spikes mean? Is it the number of spikes per second that matters? Or is it the precise timing of the spikes? Who the fuck knows. For certain types of cells in certain areas, we see that they are active (producing a lot of spikes) under certain conditions. For example, in the primary visual cortex of a cat, a cell will be active when the eye sees a line at a certain position and a certain orientation moving in a certain direction. Is the timing of these spikes important? We don’t know! Some experts believe one way, some experts believe the other, and the rest admit they don’t know. And primary visual cortex of the cat is the most well studied area of any brain in any animal.

(*) How does a spike allow communication? The voltage spike triggers the release of chemicals at “synapses” (the connections to target neurons), which in turn dock with the target cell’s membrane in various ways to allow ions to cross the membrane, thereby affecting the voltage of the targeted cell. If the voltage in a cell reaches a certain threshold, a spike will occur. Each neuron targets (and is targeted by) thousands of other neurons. And the total number of neurons in a human brain is about a fourth of the number of stars in the milky way. You wanna map that circuit?

So, the next time you see a pretty 3D picture of many neurons being simulated, think “cargo cult brain”. That simulation isn’t gonna think any more than the cargo cult planes are gonna fly. The reason is the same in both cases: We have no clue about what principles allow the real machine to operate. We can only create pretty things that are superficially similar in the ways that we currently understand, which an enlightened being (who has some vague idea how the thing actually works) would just laugh at.

Crowdsourcing a Theranos test?

Have you been following the Theranos debacle? The WSJ reported twice last week on this much-hyped Silicon Valley company which is trying to “disrupt” the blood test industry but seems to be stumbling on fraudulent methods. The company has fancy investors and even fancier board members (former Secretaries of State George Schultz and Henry Kissinger and former Secretary of Defense William Perry) and was valued early last week at $9 billion. I’m pretty sure its value has gone way down since then. Since WSJ is behind the paywall, take a look at this summary on Forbes or this one from Wired.

Well, does the blood test technology work or not? It’s frustratingly hard to know. Theranos CEO and founder, Stanford dropout, and black-turtleneck-wearing Elizabeth Holmes claims (for example at the end of this Mad Money interview from last week) there have been multiple tests of their methods against standard (more expensive) tests that require more blood. But she doesn’t provide them to the public for scrutiny. So that’s unsettling.

Here’s my idea. We crowdsource the answer to this question. It’s not a random sample but that’s ok, because we already have “ground truth” in the form of standard tests. We just want to compare Theranos blood test results against them. This guy did it already:

On June 29th I went to the Hematology lab at Stanford for routine CBC and Metabolites numbers. As I walked back to Palo Alto, I stopped by my doctor’s office, got an order, went to the Theranos office at Walgreens on University Avenue in Palo Alto and got a CBC test.

Taken one hour apart, the Stanford and Theranos HCT numbers differ by about 7%: 44.1 Theranos vs. Stanford 41.1. For platelets, the difference is even wider: Theranos 430 vs. Stanford 320

Intrigued, I got a new order and went back to Theranos the following day, on June 30th. Theranos numbers were markedly different 24 hours later: HCT 40.6; PLT 375

Just to make sure, I went back to Stanford for a second test today July 1st: Stanford HCT 41.7; PLT 297

I find the price and convenience of Theranos services attractive, but I worry about the reliability of the important HCT number. What is the confidence interval in your measurement? + or – 1 point? + or – 5 points? I do get a phlebotomy at 45. How should I look at your June 29th 44.1 HCT number?

I’m curious to hear more about your methodology, standards and quality controls and would like to give you an opportunity to respond before I write a Monday Note on the broader topic of lab exams and other healthcare mysteries.

More people should do this, preferably on the same day! Within an hour of each other, too, if possible. It’s in the public interest. We just need to set up an app or something to let people upload their results with some kind of verification method so we know it’s not spammy.

Or else we just ignore Theranos entirely, because it’s gotta be a fraud given the way they’re acting. Here’s a convincing argument from the comment section of the above first person account, someone who calls themselves Skeptical Owl:

You are the CEO of a company that has been working on a revolutionary, disruptive technology for a decade or so. This technology is so amazing that, based on price and customer experience, you can capture most of the (very large) existing market as soon as you enter it. Armed with all of these advantages, you choose to avoid allowing scientists or regulators to validate your technology, enter the marketplace through a single partner (Walgreens) at a glacial pace, and conduct most of your business using existing technologies that are not your revolutionary product. Are you choosing this strategy because your technology doesn’t actually work, because you are incompetent, or because you hate capitalism? Bonus question: if the technology doesn’t work, why is your board a Who’s Who of the military-industrial complex instead of a group of scientists who can help?

Update: I just received this email from a Theranos PR firm:

We read your coverage of Theranos with interest, and wanted to share with you that – because there has been a lot of inaccurate information in the media to date – we have posted detailed information on our technology, finger-stick test, accuracy, and conversations with The Wall Street Journal on our website: https://www.theranos.com/news/posts/custom/theranos-facts

We hope you will take the time to review the information we have posted online, and look forward to engaging with you in the future.

Regards,

Peyton Burgess, on behalf of Theranos

FTI Consulting

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Readers, for all sorts of silly and unreasonable reasons, Aunt Pythia’s schedule was too hectic yesterday for her usual advice column. However, she misses you so desperately that she decided to ignore multiple hungry children crying for crepes with nutella in order to write to you all today. (And actually, they seem to be just fine playing Minecraft for the time being.)

Before Aunt Pythia goes on, however, she has to delve into the theme of the week! Namely, celebrating getting old.

Readers, too often I come across the concept of becoming old as a form of disease, as if we are expected to pity people for the very act of aging. I say no! I say celebrate that time! I expect to be a crazy happy old person, and possibly a happy crazy one too. Heck, more than half of my problems stem from concerns I simply won’t have when I’m 75, and the other stuff will probably also seem dumb.

Part of why people are so afraid of getting old is the bizarre worshipping of youth and its beauty. I’m not arguing that young people aren’t beautiful, because they are, but I think we need to do better than just pretending we’re young when we’re not. And you might think this means letting go of vanity, but I’d argue it just means finding sagginess beautiful, which is much easier if you think about it, and something I’ve already accomplished. Give it a try!

Of course, other problems do come up, and it would suck to be in chronic pain, or to see your friends fall ill, but I would like to insist that we appreciate the freedom of thought and worry represented by the senior citizen of sound mind and body, which increasingly is reality. And that’s wonderful. Let’s focus on quality of life, people, and let’s keep our standards high!

She is awesome. I’m thinking – hoping – I’m looking at my future self. I’ll be wearing something much more garish, of course.

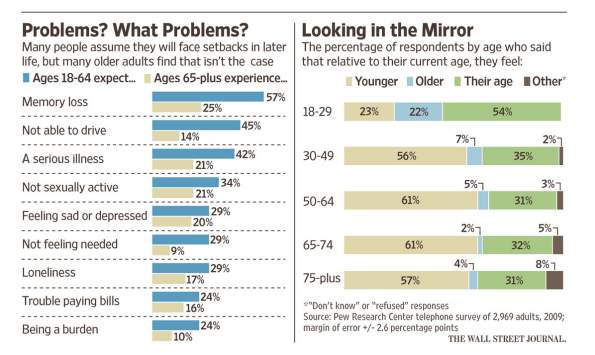

Update. if you think I’m nuts, take a look at handy chart:

I hope you all are feeling the elderly love together as you dive into the ridiculous and mostly irrelevant counseling that Aunt Pythia plans to dole out. Please enjoy! And afterwards, please:

ask Aunt Pythia any question at all at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

What’s up with finance people being assholes to each other? I work as a quant at a buy-side firm where there are separate quant and fundamental teams. It’s a pretty small shop in terms of personnel, so when I first joined I tried getting to know the coworkers outside of my team. However, this kind of stuff is a two-way street, and the impression I get – especially from the fundamental research team – is that they want to have nothing to do with what they view as a quant geek. I guess in the elbow-chafing corners of finance, one must sport an Ivy League MBA, play golf, be a part of a country club, be a smooth talker, and watch football. Obviously I’m exaggerating… or am I? Anyway, I’ve given up trying to “fit in”, which results in a lot of awkward greetings – if at all – in the hallway. Company get-togethers are an absolute dread. Is this how life is supposed to be like on the buy side, and I thought only the sell side was like this?

Work at Office Really Kinda SUCKS

Dear WORKS,

Yeah. The culture is really different outside of academia, and it’s not just in finance. I think, as a rule of thumb, you can count on the people that make the most money to feel less like being friends, and more like ignoring the “unimportant people.” Or, if the money in the two groups is somewhat similar, you can expect some weird, tribalistic competition thing to make it hard to be social in a natural way. Money is so weird.

Inside academia, it’s not super social either, but it’s less directly competitive except among really strange people. On the other hand, there is a strict hierarchy in academia that doesn’t exist outside it. The currency is professional status, not cash money, and since professional status is slightly harder to measure, it makes people slightly less focused on it. That’s my theory.

Also, about the MBA crowd: the lack of sociability might be coming more from fear of looking out of place than actual malice. Those people are highly socialized to care about external opinions and “in-crowd” status. If you actually want to be friends with them, I suggest directly approaching the most alpha of all of them – the head salesperson or equivalent – who is probably less afraid of what things look like, and also likely extremely charismatic. Once you’re buddies with that person, the others might be ok with you.

And really I’m just talking about being friendly. I’d focus on friends outside of work for stronger connections.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

You should be delighted your kids rooms are a mess. A super tidy room is a key indicator of teen mental illness, specifically food disorders. I used to joke around with my kids, hoping their rooms would be a mess.

K

Dear K,

I will try to keep that in mind. I am delighted with my kids in general.

Aunt Pythia

——

Hello Aunt Pythia,

I was just wondering when your Weapons of Math Destruction book will come out. How long will I have to wait? Enjoying your blog until then. Wishing you lots of luck with finding a good fulfilling job.

My first job was at a cooperative bank, which is owned by it’s members (thousands of them) with a one-vote-per-person-regardless-of-number-of-shares-owned system to elect the managing directors, etc. I really enjoyed working there and was proud of the work we did.

Maybe there are small nice banks (which can only pay you a fraction of what you’d make at the big ones) over there, too? Wishing you lots of luck, anyhow.

Cheers,

The Bored Bookworm

Dear TBB,

Thanks for the encouragement! Unfortunately, it’s not going to be until September 2016. I know, it makes me sad too. But that day will eventually be here.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a young woman who is a junior researcher in quantum physics. I am reasonably successful in my field and have been working with top names in Ivy Leagues throughout. I have been publishing first author work in top tier journals during my Ph.D. and postdoc, received multiple job offers/fellowships after my PhD and, was ‘top of my class’ whenever the idea of ‘class’ made sense!

Nonetheless, I not feel confident enough of my prospects in research any more. Recently, I have been thinking that a large part of my lack of confidence in my abilities stems from the constant lack of positive re-enforcement that probably everyone in academic (industrial?) research feels, in spite of evidence to the contrary. No one pats you on the back for a job well done etc., which is not entirely unexpected actually — we all do research for passion not accolades, right?

However, in my case, the situation is further exacerbated since I have felt shortchanged at various junctures throughout my research career. Be it my contributions being demeaned by treating me as an add-on afterthought on author list, or being overlooked for authorship credit altogether, to my ideas being criticized during discussions in not so pleasant and professional manner.

I try to be always professional in my dealings with my colleagues (listen to their viewpoint, never raise my voice, acknowledging their insights in the discussion etc.), but do not always find the same courtesy being extended to me especially in cases of disagreement. This, of course, happens mostly in instances where I am part of a collaborative team effort and not when I am driving the work almost completely by myself (i.e. when I am the first author).

I am an international scholar so navigating US academia was a bit of a cultural journey for me. Initially, I was the only woman on my entire floor, and when I did not see my other male colleagues struggling with the same issues — I figured that maybe it is the gender discrimination which I had only heard about till then. In a weird way, it was comforting to ascribe it to my gender, because somehow it felt so stupid and anachronistic in 21st century that it completely took away the feeling of my struggles being personal or specific to me as a person.

Gradually, however, a few more women trickled in (still the f/m ratio is 1:50), but they seemed to make it work better in terms of getting along with my male colleagues. This led me to think that it maybe something about me after all! [I am not sure how happy they were though, since I did not get to know them well enough. So it is possible that I am oblivious of their struggles!]

I have also heard from my husband and other friends, in different contexts though, that I come across as a strong personality and am not shy to voice my opinions, which in retrospect, may have proved to be a hurdle to working on teams and gelling along with everyone in the group. I have tried to ‘tone myself down’ in professional interactions keeping my opinions to myself even when I feel they may be relevant to the cause but it has only intensified my feelings of isolation. I have also been asked to be more ’empathetic’ though I am not sure what should I exactly change in my behavior professionally.

I fervently hope that I do not come across as a jerk.. 😦 I am thinking maybe I should try to get some independent money and move to a less high-nosed place than where I am currently. I have been advised against this by some who feel that given my trajectory this would look like a ‘step-down’ and a ‘failure on my part to work out an incredible opportunity’. The only other option is to leave Physics altogether at the risk of getting my heart broken initially, but I hope that I will be able to come to terms with the change, do well elsewhere and maybe be happier on the whole once the dust of this change has settled. What do you suggest?

Worried Over Misguided Antagonistic Nuisance

Dear WOMAN,

I’m glad you reached out. The first piece of advice I’d give you is to talk to more of your colleagues, not in your department necessarily but in your field. I think – no, I’m sure – you’ll find that the issues that you’re dealing with are pretty universal, both among women and men.

Let’s think about what that means, if you’d allow me to take it on faith. That means that absolutely everyone is jockeying for credit in your field. It is, possibly, exactly how power plays out, beyond the physics being done of course. It’s probably a good idea to take careful notes about what works and what doesn’t, what kind of conversations you might want to have with your collaborators before the authorship issue comes up, and so on. This is not going away, and believe me some of your colleagues think about this stuff more than they should. You don’t want to make it obsessive but you do want to give some order to the chaos, so at least you have a plan going in, and aren’t baffled every time by how things didn’t work for you or how they were surprisingly difficult.

And by the way, I’m giving you advice that I give myself. Think about things that involve power and make a plan. Not so that you take advantage of others, obviously, but so that you end up with what you think is fair. Having one-on-one conversations with people before a larger meeting gets you much closer to understanding what’s going to happen in the meeting.

The fact that you aren’t detecting frustration from your current colleagues isn’t saying much. People are good at hiding their emotions. Instead, make friends with people for real, and eventually you’ll know what’s going on with them.

Also, don’t worry about being blunt and opinionated. Whenever someone talks about how a woman is blunt and opinionated, I think about all the men who are even more completely blunt and opinionated and who never get flack for it, and I realize it works to their advantage, and that people are just trying to tame and sublimate us blunt opinionated women, and fuck that. It’s not something you can really change, anyway.

The only thing I’d suggest here is that you’re going to have a plan for these things (see above paragraph), and you don’t want to say anything that would deviate too badly from the plan. Stick to your own plan, and don’t try to change everything about yourself, just try to nail down what’s going on in these specific situations.

Finally, before you leave for another place, or leave physics altogether, I want you to think about how power plays happen everywhere, and sometimes they’re brutal, and ask yourself if you’re actually enjoying the physics you do. If you do, if you still love physics, and if you still get excited by your work, and if you can find consolation in knowing everyone is going through this stuff, not just you, and if you can imagine it getting better as you get better at managing it, then I’d say sit tight for now, talk to people around you, and devise a plan, and let it go through a few iterations before you reevaluate.

And if you simply can’t stand it, ignore me and go ahead and apply for jobs. I’m never going to tell a brilliant woman (or man) to stay in a miserable job on principle.

Good luck,

Aunt Pythia

——

Readers? Aunt Pythia loves you so much. She wants to hear from you – she needs to hear from you – and then tell you what for in a most indulgent way. Will you help her do that?

Please, pleeeeease ask her a question. She will take it seriously and answer it if she can.

Click here for a form for later or just do it now:

Romance and math meetings

As many of you know, I write a fun Saturday morning column called Aunt Pythia, where I give advice to people about all sorts of things. I typically have at least one or two questions per week (out of 4) from math people, and some of those are questions about dating and romance, from both men and women.

With some consistency, then, I get a question something like last week’s question:

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Is it perverse that one of my initial reactions to something bad happening in my life was “this ought to make good Aunt Pythia material”?!

To set the scene, I’m a young female maths PhD student, who attended a graduate school/conference a few months ago. Initially I didn’t know anyone at this conference (it was the wrong side of the atlantic) so it was great to find lots of really cool people to talk to. In particular I talked a couple of postdocs, whose research directly connects with mine. One of them, “Smith”, sent me preprint, which I excitedly read over the weekend (it was a 2 week event).

Aunt Pythia, is it wrong that our conversations at these events are not just mathematical?

Smith started paying me too much attention. Well, there are lots of other people at this conference so I can just talk to other people (I accept evasion was rather weak of me). Then during a break between lectures, in which I had elected to get on with work, he proceeded to ask me on a date. The humiliation was not even private, there were many other people remaining quietly in the room like myself.

This deeply upset me. I still like to think of myself as a serious mathematician sometimes, and so the rude awakening from my naive collaboration ambitions may account for much of that pain. Or perhaps it was the way he seemed so sure of a yes, or his remark “I can concentrate on the lectures now”.

I thought of several defiant responses to give to his question, but, alas, only hours later. My parting remark to him was “never do that to someone again”. He was misguided and somewhat upset too… I don’t think he will embarrass himself like that again anyway.

Aunt Pythia, I still can’t move on from this. I still feel the injustice when I think of it. How can I move on? Am I making too much of this?? I feel like I really want people to understand why this was upsetting for me.

Moreover, I wonder at my responsibility in this. There have been other situations in which I felt I may have won more favour than I deserved perhaps by being the female. Am I obligated to be sensitive to this bias, and reduce my level of warmth ‘just in case’? Smith is giving a seminar to my group in the near future. I’m not sure how I should behave around him, hence why moving on would be really great…

Woman not at a bar

Here was my (typical for Aunt Pythia) response:

Dear Woman,

First of all, I appreciate that certain situations are “Aunt Pythia material.” That is in fact a goal of mine, which I can now check off as “achieved.”

Second of all, I’m not really sure I understand why you are so upset. And I’m sorry for that, because as you stated, it’s important to you that other people understand this point. I am going to make some guesses because I think if I miss it, my advice will probably be totally useless. Here I go:

- You wish he had asked you in private, because it’s just a private matter and asking you in public put you on the spot too much.

- You hate him for acting like he was definitely going to get a “yes” from you, because it made you look and feel like you should be grateful for the attention and flattery, which you are not.

- You think questions of romance in the context of mathematical conferences degrade you as a mathematician, and you want to keep the two things absolutely separate.

- You think that his romantic attention, in front of other people, made them think he wasn’t taking you seriously as a mathematician, but only as a romantic or sexual interest, which might possibly make them also not take you seriously as a mathematician.

Now, just as an exercise, I want to imagine what this guy’s perspective on the whole thing was. Various versions as well:

- He met this amazing, brilliant math nerd and he thought things were going really well – they were talking about all kinds of things, not just math – but when he asked her on a proper date, she got really mad and told him never to “do that” to someone again, which confused him. Do what? He ended up sad.

- He met this amazing, brilliant math nerd and he thought things were going really well – they were talking about all kinds of things, not just math – but when he asked her on a proper date, she got really mad and told him never to “do that” to someone again. After thinking about it a while, he realized that he had put her on the spot and hadn’t judged the situation properly. He wants to apologize to her and remain friends (and he still has a crush on her, but whatever) but he’s not sure how to do it. He vows to be more careful and more private in the future.

- He met this amazing, brilliant math nerd and was really into other people seeing him score with her, so he asked her out in front of them, but it didn’t work out because she was onto him and called him out on it. He’s going to have to revise his plan in the future.

- He pretended to be interested in a female mathematician’s work so he could get down her pants. Plan failed with that one but he moved on to the next in line.

OK, so I am not sure which scenario you think this guy fits into – if any – but personal guess, bases on what I know, is he’s a #1. The thing about men (and women) is that nobody knows what they’re doing, but mostly they’re not trying to be bad people.

I’m not saying there aren’t people like #4, but I don’t want to assume anyone, ever, is actually like that unless I have really large piles of evidence. So I am advising you to give him the benefit of the doubt and assume he was just crushing out on you and had no idea that you’d be uncomfortable with the situation.

I also don’t see why you can’t collaborate with this guy. Honestly. Having a crush on you is his problem, not yours. I’d even say that crushing out on your collaborators might help the work. Certainly keeps it interesting, and it doesn’t have to lead anywhere or even mean anything. Honestly I don’t know if I can work with someone without developing something of a crush on them.

I don’t actually think we can separate our mathematical selves from our self selves, and sexual/romantic parts of us emerge no matter how hard we try to restrict them. That’s not to say the guy should have put you on the spot – I agree with you that it was an awkward if not somewhat hostile move – but I don’t think it makes sense to assume that working on math with someone isn’t an intimate thing to do.

In any case, if and when this happens again, feel free to have a response memorized along the lines of, “I really don’t want to date people within my field, it’s just not my style. But thanks anyway.” That way it’s not about them, and the answer is final.

The one thing I feel I should object to is the use of “injustice.” I think that’s going too far. The guy didn’t impugn your honor, integrity, or mathematical talent. He simply asked you out in the wrong time and place. Put it this way: you’re going to need a thicker skin to be a woman warrior in mathematics. Sad but true. Save the word “injustice” for when it’s really needed.

Here’s my advice about his upcoming visit. Go to his seminar, ask really good questions. Be a mathematician. Be warm because that’s who you are. Be attractive because that’s who you are. Don’t worry about people being falsely attracted to you because it’s real. And it’s not anyone’s fault and it’s actually awesome. Oh, and everyone has it to some extent, tall men especially, and they don’t feel weird about the attention they receive. Feel free to turn your attention to others when someone is being weird.

Good luck,

Aunt Pythia

This generated a ton of comments, much more than usual for an Aunt Pythia column, and you can read them here. The debate is great, and it’s made me think about this issue much more, and I’ve come to the conclusion that I gave bad advice.

Wait, let me rephrase that. I have come to the conclusion that I was wrong about this issue, but at the end of the day I think I might stick by my advice in the final paragraph. Here’s my thinking about it.

First of all, a very personal confession. I am a pro-love hippy throwback from the 1960’s. That means a few things, and I probably wouldn’t even be writing Aunt Pythia if I weren’t weird in all sorts of ways, but the consequences that are most relevant to this discussion are the following:

- As a pro-love hippy throwback from the 1960’s, I do not find it inherently bad if someone is attracted to me in a romantic, sexual, or really any sort of way. In fact, I think it’s great news! More love is good!

- I crush out on people all the time, and I always have. If my friends stopped hanging out with me every time I hit on them, I would have no friends (thanks for the forbearance, friends!). I think of it as “part of my charm,” but it also has the effect of surrounding me with people who are, in general, also somewhat pro-love hippy throwbacks. It’s a selection bias thing.

- As a pro-love hippy throwback from the 1960’s, I am simply not awkward about this issue, and indeed I don’t even see a reason to be (see above selection bias). What this means is that if someone expresses a desire to date me or have sex with me that I don’t reciprocate, I don’t get at all alarmed, and I don’t feel any responsibility towards them, or awkwardness, or anything really other than a mild sense of flattery. It happens enough that I have a crush on someone that they don’t reciprocate (because I crush out on people all the time) that I know it’s no big deal. And it almost never is.

- In particular, it would never occur to me to rule out someone as a potential mathematical (or otherwise) collaborator because they expressed sexual or romantic interest in me. Here’s why. From my weird perspective, my brain is my best feature, and I would assume it means they are really into my brain, i.e. working together. I don’t tend to separate different kinds of attraction, because I don’t think it’s possible. So if someone is ambivalent to the way I look when they meet me, and then they talk to me a while and love the way I think, then they might end up being super attracted to me. I think that’s normal. In any case I don’t think someone being attracted to me sexually is a sign they don’t take me seriously as a thinker. That has certainly not been my experience.

- Having said that, if someone exhibited harassing tendencies: stalking me, not taking no for an answer, threatening me in any way, or even just being overtly sexual with me when I’ve already politely declined, then yes, I would totally think the person was a stinky jerk.

- And here’s the final, important part of my confession: that very rarely happens to me. I think it’s a combination of my body type (extra large) and my personality (extrovert), but I very rarely get hit on by men who are creepy. Those men do not see me as a potential victim of their harassing ways.

As a result of my above confession, when I heard about someone who gets asked out by a man, I honestly didn’t understand why she would be upset. But here’s the thing, I’m weird, and I know that. So I shouldn’t assume all women relate to sexual and romantic attention the way I do. In fact, they don’t, as I have (slowly!) learned over the years from my readers.

Many of the people who commented on the thread mentioned that, when a romantic or sexual interest has been expressed between two people, things get extra complicated, and it makes it much more difficult to work with someone collaboratively. This is not true for me, but it’s true for enough other people that I should just assume it’s true. So for now let’s work with the following simplified and slightly cartoonish assumption (and I apologize for being heterosexist but I’m doing so for clarity, and I’m not sure if it applies to gay relationships):

Assumption A: if a man or a woman has expressed interest in being sexually or romantically involved with the other, they can no longer do math together.

Given Assumption A, I can absolutely understand why Woman not at a bar was upset about the event. It meant that she was no longer capable of working with this guy whose math she was interested in. That’s a huge loss, and it’s upsetting.

Moreover, and here I’m simply repeating what a bunch of people on my comment thread explained to me, it’s something that the guy did to Woman not at the bar, which is not cool because she has no power to undo it. It’s like, imagine she has a list of “possible collaborators” and he just went and crossed out his name from her list.

OK, now let’s do some simple reckoning and figure out why Assumption A causes a problem in general. The field of math is deeply lopsided, with many more men than women. If the women are all hit on by men, then they all exclude themselves as collaborators. This isn’t much of a problem for the men, who have plenty of other potential collaborators, but it is a huge problem for the women. They end up with very short lists.

Altogether, it really looks like Assumption A is a major problem, even if it’s expressed in a hyperbolic way and is only somewhat true, and even if it’s not true for all women but only a majority. My new advice towards math men will be in the future: don’t ask out other women in math, and certainly not in your own field, and most definitely not in the context of a math conference.

It makes me sad to say this, I need to confess, because I personally love math guys and I think they’re wonderful partners, and of course I’m married to one of them. But I really do get the logic, and for as long as a version of Assumption A holds, I think it’s kind of an inevitable loss. So yeah, I was wrong about this. I’ve changed my mind.

Next, and I’m sorry if I’m beating a dead horse, I do want to go back to my advice for Woman not at a bar:

Here’s my advice about his upcoming visit. Go to his seminar, ask really good questions. Be a mathematician. Be warm because that’s who you are. Be attractive because that’s who you are. Don’t worry about people being falsely attracted to you because it’s real. And it’s not anyone’s fault and it’s actually awesome. Oh, and everyone has it to some extent, tall men especially, and they don’t feel weird about the attention they receive. Feel free to turn your attention to others when someone is being weird.

I still stand by this advice. I don’t think that we should try to give Assumption A any more power than it already has. If I could, I would try to convince people to discard it altogether, because ultimately I do think it’s a choice that people make inside their heads, it’s not a god-given truth, and as such it deserves to be examined and ignored if it is deemed not useful. And if there’s anything that’s not useful, it’s a rule that limits options for women’s math careers, which is already unduly difficult for so many other reasons.

My final word on this is this: I do think we’re in danger of conflating two issues, namely sexuality and sexism. I have experienced enough toxic sexism in my life, that had absolutely nothing to do with sexuality, that I worry we’re making unnecessarily strong cultural rules around sex where we should be thinking longer and harder about structural and institutional sexism, which is the real problem. And of course there are confusing combinations of the two, like this guy, where there are sexual predators and they’re also sexist, and to be clear it’s never ok to be sexual with someone who is your student or someone whose career you influence.

Microfinance is mostly a scam

I might be well behind others on this subject, but I’m trying to catch up. I just finished a book entitled Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic: how microfinance lost its way and betrayed the poor, written by Hugh Sinclair. Published in 2012, it reviews the previous decade or so of microfinance institutions and how there are essentially very few that haven’t become loan sharks for poor people.

The promise of microfinance was this: that poor people are budding entrepreneurs, who simply don’t have access to the capital required to make their dreams come true. Turns out that’s pretty rare in practice, and that 90% of the loans taken out are “consumption loans,” meaning they are used to buy something like a TV or a service, and then some part of the remaining 10% are loans taken out to repay other loans, and so the “investment loans” are down to small single digits.

There’s a success story given in the book of a female Mongolian “head processor,” who takes unused body parts and salvages them, and who borrows money to buy an electric grinder to improve efficiency so she can grind multiple brains per day, and then when that improves her business she buys a freezer so she can buy heads in bulk more cheaply and store them, which improves her business yet again.

It’s a nice story, but of course it means, even in this best case, that the people around her who had previously done what she now does have been pushed out of business. They need to find a new job.

And by the way, the example above happened in Mongolia, which has strict and enforced usury laws, which keeps the loans down to something like 30% annual interest. In other places there are weak laws and little or no enforcement, and the interest rates, if you include fees and tricks, are upwards of 140% (in Nigeria) or even 200% (in Mexico).

Let’s face it, that kind of extortionist interest rate doesn’t anyone. So we come to a basic question: how can that possibly happen under the guise of helping the poor?

The answer is that there’s an inherent conflict of interest between making profitable loans and helping the poor, and greed nearly always wins. Moreover, the feel-good message of helping the poor just seems too good to give up. It’s really sad but also entirely convincing.

The author, Hugh Sinclair, chronicles his efforts to whistle-blow on one particularly egregious microfinance firm in Nigeria, called LAPO, which still seems to exist. He was basically given the job of establishing a better IT system, which means he got to see all the data. I’ve often said, cynically, that companies don’t really want data consultants because those consultants get to see the most embarrassing stuff. Well, in this case the most cynical of readings is true, and Sinclair saw everything and was disgusted by the way LAPO treated its customers, doing stuff like making them put a 20% deposit but charging them on the whole loan, miscalculating their interest rates, using their deposits for further loans, and of course having them sign a form they didn’t understand. Their astronomical interest rates made it impossible for their customers to actually benefit at all.

In fact some of the stuff he uncovered was actually illegal, but it didn’t stop the practices, and even when Sinclair went back to the so-called “microfinance funds” and told them about LAPO, it didn’t stop them from investing, even the one he worked for at the time. Microfinance funds collect money from investors and governments, and their job is due diligence, but they weren’t doing it, nor did they appreciate Sinclair’s attention to that fact, because their investors might get spooked and because the entire house of cards was at risk of falling.

Sinclair also makes a convincing case that regulations and tough regulators are absolutely necessary if we’re going to have widespread loans, and that due diligence is a difficult thing to do from afar but is absolutely required. Not surprisingly, the countries where the most micro-finance occurred are also ones that don’t have such strong regulatory infrastructure (although who does, really?).

The one part of the system that got a lot of credit was, interestingly, the independent credit rating companies, who knew their stuff and refused to be cowed, even through they got paid by their clients, the microfinance funds. That’s nice to hear and is certainly unusual.

At the end of the book Sinclair adds a convincing “Microfinance 101” section that explains how most of the entrepreneurial efforts that the poor are likely to engage in are nothing more than microfinance arms races that do little to help the local economies but do one thing for sure, namely impose a tax on business that is taken out of the local community entirely and distributed back to the rich world in the form of the investors.

Since the book came out, some economists have performed experiments to test microfinance, in the “best case scenario” conditions, i.e. no loan sharking, and they’ve basically found no benefit. Here’s one of them.

My conclusion is that microfinance is a failure in almost all ways, and for almost all people.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Readers, today I’m celebrating hair.

I think people under-appreciate hair, especially in this climate of shaving everywhere and everything, and I think we need a good old 1970’s style comeback of hair. Big hair, bushy hair, facial hair, leg hair, pubes, and armpit hair. This guy knows what I’m talking about:

Who’s with me?! WHO CAN GET BEHIND HAIR THIS MORNING!?

If you’re still in doubt, read this and get back to me. I thought so.

OK, now that we’re all in hair agreement, it’s time for really terrible advice from yours truly. Please enjoy! And afterwards, please:

ask Aunt Pythia any question at all at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Is it perverse that one of my initial reactions to something bad happening in my life was “this ought to make good Aunt Pythia material”?!

To set the scene, I’m a young female maths PhD student, who attended a graduate school/conference a few months ago. Initially I didn’t know anyone at this conference (it was the wrong side of the atlantic) so it was great to find lots of really cool people to talk to. In particular I talked a couple of postdocs, whose research directly connects with mine. One of them, “Smith”, sent me preprint, which I exitedly read over the weekend (it was a 2 week event).

Aunt Pythia, is it wrong that our conversations at these events are not just mathematical?

Smith started paying me too much attention. Well, there are lots of other people at this conference so I can just talk to other people (I accept evasion was rather weak of me). Then during a break between lectures, in which I had elected to get on with work, he proceeded to ask me on a date. The humiliation was not even private, there were many other people remaining quietly in the room like myself.

This deeply upset me. I still like to think of myself as a serious mathematician sometimes, and so the rude awakening from my naive collaboration ambitions may account for much of that pain. Or perhaps it was the way he seemed so sure of a yes, or his remark “I can concentrate on the lectures now”.

I thought of several defiant responses to give to his question, but, alas, only hours later. My parting remark to him was “never do that to someone again”. He was misguided and somewhat upset too… I don’t think he will embarrass himself like that again anyway.

Aunt Pythia, I still can’t move on from this. I still feel the injustice when I think of it. How can I move on? Am I making too much of this?? I feel like I really want people to understand why this was upsetting for me.

Moreover, I wonder at my responsibility in this. There have been other situations in which I felt I may have won more favour than I deserved perhaps by being the female. Am I obligated to be sensitive to this bias, and reduce my level of warmth ‘just in case’? Smith is giving a seminar to my group in the near future. I’m not sure how I should behave around him, hence why moving on would be really great…

Woman not at a bar

Dear Woman,

First of all, I appreciate that certain situations are “Aunt Pythia material.” That is in fact a goal of mine, which I can now check off as “achieved.”

Second of all, I’m not really sure I understand why you are so upset. And I’m sorry for that, because as you stated, it’s important to you that other people understand this point. I am going to make some guesses because I think if I miss it, my advice will probably be totally useless. Here I go:

- You wish he had asked you in private, because it’s just a private matter and asking you in public put you on the spot too much.

- You hate him for acting like he was definitely going to get a “yes” from you, because it made you look and feel like you should be grateful for the attention and flattery, which you are not.

- You think questions of romance in the context of mathematical conferences degrade you as a mathematician, and you want to keep the two things absolutely separate.

- You think that his romantic attention, in front of other people, made them think he wasn’t taking you seriously as a mathematician, but only as a romantic or sexual interest, which might possibly make them also not take you seriously as a mathematician.

Now, just as an exercise, I want to imagine what this guy’s perspective on the whole thing was. Various versions as well:

- He met this amazing, brilliant math nerd and he thought things were going really well – they were talking about all kinds of things, not just math – but when he asked her on a proper date, she got really mad and told him never to “do that” to someone again, which confused him. Do what? He ended up sad.

- He met this amazing, brilliant math nerd and he thought things were going really well – they were talking about all kinds of things, not just math – but when he asked her on a proper date, she got really mad and told him never to “do that” to someone again. After thinking about it a while, he realized that he had put her on the spot and hadn’t judged the situation properly. He wants to apologize to her and remain friends (and he still has a crush on her, but whatever) but he’s not sure how to do it. He vows to be more careful and more private in the future.