The US political system serves special interests and the rich

A paper written by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page and entitled Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens has been recently released and reported on (h/t Michael Crimmins) that studies who has influence on policy in the United States.

Here’s an excerpt from the abstract of the paper:

Multivariate analysis indicates that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.

A word about “little or no independent influence”: the above should be interpreted to mean that average citizens and mass-based groups only win when their interests align with economic elites, which happens sometimes, or business interests, which rarely happens. It doesn’t mean that average citizens and mass-based interest groups never ever get what they want.

There’s actually a lot more to the abstract, about abstract concepts of political influence, but I’m ignoring that to get to the data and the model.

The data

The found lots of polls on specific issues that were yes/no and included information about income to determine what poor people (10th percentile) thought about a specific issue, what an average (median income) person thought, and what a wealthy (90th percentile) person thought. They independently corroborated that their definition of wealthy was highly correlated, in terms of opinion, to other stronger (98th percentile) definitions. In fact they make the case that using 90th percentile instead of 98th actually underestimates the influence of wealthy people.

For the sake of interest groups and their opinions on public policy, they had a list of 43 interest groups (consisting of 29 business groups, 11 mass-based groups, and 3 others) that they considered “powerful” and they used domain expertise to estimate how many would oppose or be in favor of a given issue, and more or less took the difference, although they actually did something a bit fancier to reduce the influence of outliers:

Net Interest Group Alignment = ln(# Strongly Favor + [0.5 * # Somewhat Favor] + 1) – ln(#

Strongly Oppose + [0.5 * # Somewhat Oppose] + 1).

Finally, they pored over records to see what policy changes were actually made in the 4 year period after the polls.

Statistics

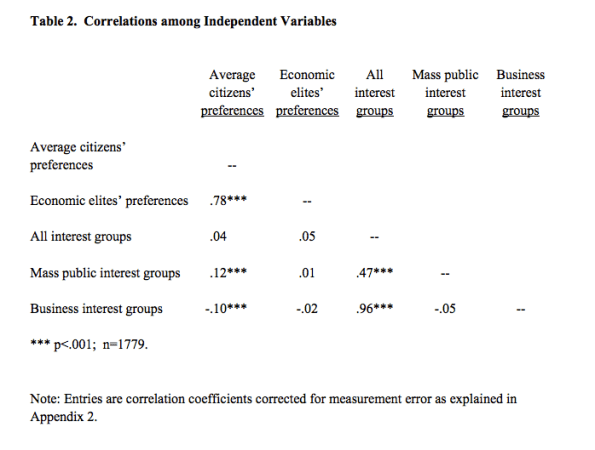

The different groups had opinions that were sometimes highly correlated:

Note the low correlation between mass public interest groups (like unions, pro-life, NRA, etc) and average citizens’ preferences and the negative correlation between business interests and elites’ preferences.

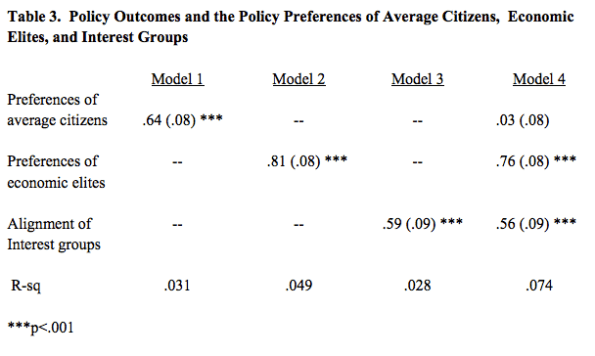

Next they did three bivariate regressions, measuring the influence of each of the groups separately, as well as one including all three, and got the following:

This is where we get our conclusion that average citizens don’t have independent influence, because of this near-zero coefficient in Model 4. But note that if we ignore elites and interest groups, we do have 0.64 in Model 1, which indicates that preferences of the average citizens are correlated with outcomes.

The overall conclusion is that policy changes are determined by the elites and the interest groups.

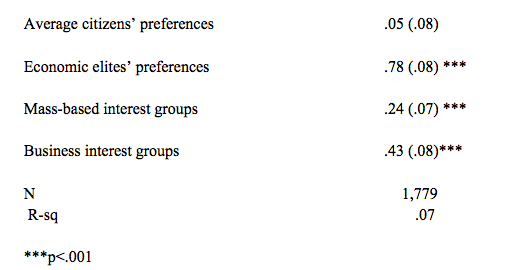

We can divide the interest groups into business versus mass-based and check out how the influence is divided between the four defined groups:

Caveats

This stuff might depend a lot on various choices the modelers made as well as their proxies. It doesn’t pick up on smaller special interest groups. It doesn’t account for all possible sources of influence and so on. I’d love to see it redone with other choices. But I’m impressed anyway with all the work they put into this.

I’ll let the authors have the last word:

What do our findings say about democracy in America? They certainly constitute troubling news for advocates of “populistic” democracy, who want governments to respond primarily or exclusively to the policy preferences of their citizens. In the United States, our findings indicate, the majority does not rule — at least not in the causal sense of actually determining policy outcomes. When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the U.S. political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it.

So discouraging to see what I’ve believed for the last 2 decades actually put into empirical, quantitative terms 😦

Contrary to what politicians like to tell us, it seems possible that America’s best days are behind her.

LikeLike

The colonial design is not meant to accommodate the massive scale of modern society, and the participation of the individual has been correspondingly eroded.

No one has ever addressed the scaling-gap between the constitutional democracy that the colonial fathers put in place for a yeoman nation, based on small groups and short-term outcomes that were clearly observable — and the bureaucratically administered state, with outcomes that may not be observable for generations (eg., social security).

LikeLike

This is exactly the system the Founding Fathers brought into existence with a legislative model that was 1) fairly suspicious of popular democracy 2) also had the structural imperative of protecting Southern states desire to continue slavery. The result is that we don’t live in a democracy (i.e, based on majority rule) but a consensus based system (which is what the OP study is demonstrating).

I.e., after the electoral process you have a legislative process shaped by Congressional committees, inter-chamber conferences reconciling the dual track system, Senatorial disproportionality (of which the filibuster is just a symptom), the presidential veto, judicial review, limits imposed by federalism, etc. The system is so cumbersome and anti-democratic, powerful minorities can derail legislation at a wide variety of points. Most of the major players literally do have to agree. The only reason that Congress gets anything done at all, is because of the budget/omnibus process, where to avoid political embarrassment, legislative power brokers cut deals on a narrow range of issues in a narrow time frame. (see Dahl, How Democratic is the American Constitution, Lazare – Frozen Republic, Greider – Who Will Tell The People).

And small government/devolution advocates are even more fanciful in that states legislatures typically copy the federal models and are more open to corrupt influences and lobbying given even lower rates of electoral participation.

The most positive thing you can say about the origin of the American system is that it had no model of national representative government to base itself on. Given that we typically take many decades (70 years in years, at least, in the case of national health care) to recapitulate policy that is politically popular in all the other advanced democracies, I think we safely say the American model is a failure.

LikeLike

This statement of yours:

“It doesn’t account for all possible sources of influence”

captures what could be a problem with their analysis based on just having read your overview of it and not the actual paper. What we’ve learned from public choice theory and what’s probably obvious to anyone who’s thought about it is that elected officials have policy preferences too. These preferences no doubt affect policy outcomes since presumably they affect how elected officials vote. Also elected officials’ preferences may be correlated with at least one of the independent variables included in their models. For example, elite preferences or business preferences may be correlated with elected officials’ preferences. From what I could tell they didn’t include these officials’ preferences in any of their models. So the the least squares (assuming that’s what they did) estimator of the coefficients in their final model might be biased—so called omitted variable bias.

LikeLike

Hate to blather on but the previous observations don’t even take into account the party system (which again is shaped by the Constitution). In short, there is very little accountability of political elites through elections in our system. It takes genuine inter-party competition to make parties compliant to their own electoral promises and ideology. Two parties, in the same way economic duopolies work, are not competitive enough to make this happen (one symptom is the US parties are not really parties but loose coalitions with very little internal member discipline – e.g. the party platforms are for show, not binding agreements with the electorate).

Btw, the minority party can afford to have more central coordination, ie. GOP (mainly through a funding/electoral/lobbying/communication infrastructure), because it’s chief strategy is to block legislation/consensus not to accrue majorities to promote new legislation.

LikeLike

We live in a representative plutocracy. You can’t directly buy laws… But you can donate almost arbitrarily large sums to have your privilege instituted in law. Unions, businesses, and individuals have the same right… So it’s fair, right?

LikeLike

Seems like a lot of effort for a trivial conclusion.

(1) The United States is not now nor has it ever been a populist democracy — it is a constitutional republic with a representative government that is explicitly designed to filter popular preferences. Doing a study to prove this is like doing a study to prove that 2+2=4.

(2) The “conclusion” that policy changes are determined by elites is also by definition true; I never personally had an opportunity to vote for or against Obamacare, but my Representative and Senator did.

(3) Surveys are a poor measure of public preference. It is very easy to express an opinion in a survey, but more difficult to organize and lobby for or against a particular measure. At present, surveys show that the public wants to repeal Obamacare, but there is little chance the bill will be repealed any time soon.

LikeLike

We don’t have ONE government, instead we have many different layers. At the local level, a lot of mundane issues get resolved to the citizen’s satisfaction. We used to have a Senator whose nickname was Senator Pothole, did he allocate money for fixing potholes to satisfy big business or to curry favor with voters? Does it really matter? He got the job done. When my wife graduated from Berkeley and needed to accelerate her citizenship application for a job, we turned to Congressman Ron Dellum’s office and they helped. We were certainly not elite in any sense, “Special interests” include all sorts of groups, such as teachers’ unions, moveon.org, as well as business groups. They all have special interests, sometimes even aligned with regular citizens.

LikeLike

thx for covering this. its an eyepopper if you ask me. serious scientific analysis of a broken system, a systemic issue, hope it continues and research insight strengthens. reminds me of increasing scientific interest in global warming. yes there seems to be a sort of Matrix reality going on in politics and has been going on for decades as there is a increasing divergency between the illusion and the reality and the lack of awareness of the illusion. “none are more enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free” —goethe. there are also many strong parallels with rome. the role of financialization and military-industrial-complex (public funding of the military approaches 50% of the entire budget but this is largely concealed) are key parts of the picture. another recent study was the centralization of financial control into a small interconnected set of corporations. stunning stuff! hope to see a comprehensive survey on these new scientific ideas/realizations sometime….

LikeLike

Perhaps our system is broken, or perhaps it is operating in the self-correcting manner the founders had envisioned. Either way, I do know from having escaped from a Communist country which was truly not free, that this is the most free country that I’ve lived in. BTW, my uncle paid good money for the two failed attempts and the final successful attempt to help my mom, my sister and myself escape from that hell hole, while he himself stayed behind due to his father-in-law’s inability to leave. It is a real shame that some free people have the illusion that they are enslaved, not understanding what it truly means to be enslaved. Another uncle who survived both Nazi enslavement and Siberian enslavement, then lived freely in this glorious country would have strongly disagreed with your assessment.

LikeLike

thats quite a point but does suggest that freedom is an ongoing, evolutionary process and that it can take detours such as in the age we live in with record wealth inequality unseed in this country since around a century. and the public is not too cognizant of that extreme (a major reason it has reached such extremes). there are different kinds of freedom, such as freedom from physical incarceration, but there does exist a kind of subtle widespread economic incarceration. freedom is indeed relative as you point out. we are free-er that our forefathers thanks to their sacrifices. my question is, will our children be free-er than us due to our sacrifices, or will they be more enslaved due to our inaction?

LikeLike

abe, You might consider that comparing the US to a Communist country is an incredibly “low bar”. To contrast, I’ve heard Western Europeans express profound criticisms of the US (including its supposed levels of freedoms) even though these critics often appreciate the US in many ways.

LikeLike

I am not surprised that Western Europeans appreciate the US in many ways as we have a lot to offer. OTOH, the Western European bar on freedom is not that high. Trying to ban ritual slaughter of animals (kosher for Jews, halal for Muslims), and trying to ban ritual male circumcision (Jews & Muslims) are not exactly signs of freedom – or tolerance.

LikeLike