Comparative advantage in international trade and in married life

What is Comparative Advantage?

You may have heard about comparative advantage. As a concept, it’s a neat and mathematically valid argument. It goes like this, as described in wikipedia:

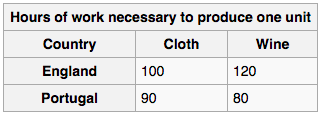

Say you have two countries, England and Portugal, which both make and use cloth and wine, say at time 1. Their productivity is described in this chart:

Which is to say that in England, it takes more work than in Portugal to produce one unit of either cloth or wine, maybe because of climate differences. In this sense, Portugal has an “absolute advantage” over England in both categories.

However, as I said, both England and Portugal make and use both products. So, if England needs one unit of each, it takes them 220 hours, and if Portugal wishes to consumer one unit of each, it takes them 170 hours to produce it.

Here’s where trade comes in. Starting at time 2, they decide to cooperate. Let’s say England focused on cloth, and make 2 units of cloth. That would take them 200 hours instead of 220 earlier. And let’s also assume Portugal focused on what it’s good at, namely making 2 units of wine. That would take them 160 hours, instead of 170. Then the countries could trade their extra units to each other, and both of them would have saved time and would have gotten the same amount of stuff.

Actually, there’s another way of thinking about it. Instead of working less, workers in England and Portugal could work the same number of hours and produce more stuff. They could use their extra stuff to trade for new things, and that excess would essentially be proof that this comparative advantage theory is a success.

Criticisms of Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage is used as a reason that countries should engage whenever possible in free trade; it’s almost a religious belief for some economists. But, as you might have anticipated, there are some serious issues with comparative advantage. For example:

- When comparative advantage kicks in for a given industry, the people in that industry lose jobs. Like wine-makers in England in the above example. Even cloth makers in England might lose jobs if the actual demand for cloth is limited. Of course, the idea is that the economy of England as a whole benefits, so a few jobs lost should somehow be absorbed.

- Also, you can’t simply expect the country that’s the best at a certain thing to be able to arbitrarily expand that industry and forget everything else. Think overfishing, or overgrazing: eventually there are diminishing returns.

- Next, technology comes into play. When one country figures out how to be incredibly productive due to technological advantages, like for example huge farming machines and equipment, then it’s essentially impossible for other countries, without access to such technology, to compete, even if they have good climates. That means most farmers in other countries cannot compete with the United States from a productivity standpoint, for example, even putting aside the ludicrous farm bill, which subsidizes American farmers and further distorts their advantage.

- Speaking of distortions, one argument against comparative advantage is that historically countries didn’t actually become powerful through exploiting comparative advantage and free trade. Instead, they imposed tariffs and such to nourish and grow internal industries.

- If a country buys into comparative advantage, by need or by choice, they often find themselves overreliant on one product, the market of which could be volatile or fail. There’s plenty of historical evidence that this monoculture approach to economics is a bad idea. For example, Ireland went through a famine when there was a blight on their potatoes, even while it was exporting huge amounts of “money crop” grains to England, and more recently Ireland focused heavily on finance and technology, only to be severely hurt by the credit crisis.

- Mostly, though, what is most troublesome about the modern worshipping of comparative advantage is that we end up using it as an excuse to exploit people. As my friend Jordan Ellenberg explained:

If you apply comparative advantage to, say, the US and Bangladesh, what you get is “given existing conditions, the US should make computers, not work very hard, and be rich, Bangladesh should stitch T-shirts for Old Navy at 30 cents an hour, work really hard, and be poor.”

- Not that they don’t want jobs in Bangladesh. They do, and generally speaking trade agreements with poor countries help people in those countries. It’s just that we have to also acknowledge our moral responsibility to people and to reasonable working conditions.

How does this relate to marriage?

Well, first let’s think about how to apply the theory of comparative advantage to a marriage, which people tend to do. The idea is that, instead of splitting up the chores with your spouse half and half, which causes unending arguments about whose turn it is, as well as wasted productivity, we instead decide “who’s good at what” and divvy up the chores in a more scientific manner.

Growing up, I did almost all the household chores while my brother did very few (and the ones we kids didn’t do, my mother did). it wasn’t because my parents told me that, as a girl, I was the natural choice, but because I just “seemed better” at everything. The result was that I did everything, and slowly my “advantage” over my brother – defined here as efficiency, not actual advantage – which was at first small, became large.

Of course nowadays parents rarely ask their kids to do chores, so chores have mostly become a marital dispute. And given that women are expected to be – and have been trained to be – both better at and more willing to do housework, they tend to have more practice at multi-tasking and the dishes.

We arrive at a problem similar to the Bangladesh/ US situation above. Again, Jordan nailed it:

In the sexist soup straight couples all swim in, “don’t keep score, everybody do what you’re best at” seems to invariably end up at the equilibrium “woman does 75% of the shitwork” and what the comparative advantage crowd says is you are not even allowed to be mad about this, women, it is ratified by science, accept that like the Bangladeshis you are in your proper place in the equilibrium state.

One of the problems with applying an economic theory to a marriage is that we don’t actually keep track of how much time it takes us to do various things, and even if we did do that we’d probably do it wrong. Just imagining watching the clock during dishes or laundry sounds silly, and never mind with being in charge of the grocery list, since depending on how you measure that, it could either take no time at all or take all your time. Plus, when you find yourself being petty about small things, you end up measuring your marriage along those petty lines, and even thinking about it that way.

My advice to married couples is to ignore scientific arguments, and instead think about a system that will minimize longterm resentment, which is poison in any marriage or relationship. And that might mean using comparative advantage in part, both as a way of figuring out what people are good at and what people like to do, but it will also probably include doing stuff that you hate and you’re bad at sometimes just to understand what the other person goes through.

After all, the essential ingredients in any marriage is a sense of teamwork, the dedication to alleviating the other person’s suffering, and a promise to encouraging one another’s fulfillment. And economics doesn’t have much to say about those things.

Good point — economic analysis is good for … economists.

LikeLike

Compare also to the need to develop new skills among workers in a business. I’ve fallen into traps in the past where I was clearly the most efficient at some job, and therefore wound up doing it all the time, by my own choice. But on reflection, that’s disadvantageous (a) to me, because the over-focus is making my other skills fragile, (b) co-workers, who aren’t getting the chance to learn and develop new skills, and (c) the business, under the “hit by bus” principle, wherein if I leave then the business may lose all institutional knowledge of that task.

The vulnerability of a monoculture is a very strong argument here. Some redundancy needs to be built into the system; perfect efficiency is perfectly fragile (think also: error-correcting codes, checksums, etc.). In the marriage or like partnership, we should be growing both partners so they can stand on their own if need be (whenever death or divorce occurs). Too many people are rendered incapacitated on separation due to inability to manage finances, food, household, etc.; I would want everyone to have some education and practice at all of those tasks (but then I am generally aligned with 70’s-style feminism).

LikeLike

What’s happening in heterosexual marriages isn’t comparative advantage being misapplied. It’s the other facts that go into the process, it’s wrong because the trades themselves were unfairly biased (unfair negotiating) or the amount of labor originally expected of both parties is unequal. If you both, originally, have to do 50% of the chores, and (as in your example) the woman is better at every task, then if they trade according to a reasonably fair system (say, every trade will save both the Woman and the man an equal amount of time which if there is a surplus, is always possible), then not only will both the man and the woman be compensated in absoute time for there trade, the Wife will end up spending less time working than the Husband, which is some compensation, although not enough, for her being sexistly trained to be better at housework.

LikeLike

Aren’t both of your marriage examples actually examples of absolute advantage? Absolute advantage is: “I’m better at both dishes and laundry than my brother/husband, so I do both”. Comparative advantage is “I’m better at both dishes and laundry than my brother/husband. He does a passable job at laundry but sucks at dishes, so I do dishes and he does laundry.”

Viewing comparative advantage as a “scientific” way to view a marriage is probably a mistake. Measuring time required to do chores is hard enough, but arguably the more important consideration is tolerance for the chore. To use comparative advantage effectively in a marriage, use statements like “I know you hate doing ____. I’ll do that if you do ______.”

LikeLike

I think the point is that dishes and laundry aren’t the only things that have to be done. The way this plays out in real life is “I’m better at both dishes and laundry than my husband, we’re equally good at playing with the kids, so I’ll do all the dishes and laundry and you play with the kids.” And lots of men all over the world coincidentally happen to be “bad at” the tasks that are less enjoyable and rewarding.

LikeLike

I could not agree more. Just as an example, my partner and I each do our own laundry. This seems inefficient compared to some other schemes, but with respect to doing away with resentment, it works *perfectly*.

LikeLike

This fits with your previous post about strategic thinking in dating relationships: who is behaving more strategically, whether intentionally or intuitively? Here are some examples that I’ve witnessed in other couples (all my own relationships being, of course, perfect models of fairness):

1) partner A can’t stand dirty dishes, partner B doesn’t mind at all if the sink fills up. Partner A ends up washing all the dishes.

2) partner A believes in nutritious food for all, partner B would be happy ordering pizza every night. Partner A ends up grocery shopping and cooking.

3) Partner B does a task that is usually done by partner A. Task is not done to the satisfaction of partner A, resulting in criticism, reduced likelihood/frequency of partner B taking/being given the task in future, and reduced autonomy when partner B does that task again.

Of course, these are taking out of context and caricature the situation, but I think flag an important dynamic.

Taking the last point a bit further, I see this happen a lot between parents (both genders) and kids: kid tries to help, parent isn’t happy with quality/timing of the help, kid ends up with a bad experience and lesson that they shouldn’t try to help anymore.

LikeLike

Regarding marital division of labor, there’s an important point being missed here about the *value* of the services being performed. In many marriage conflicts, it’s not just about who is doing how much work. It’s about what work needs to be done and when. For example, how often and how thoroughly does the house need to be cleaned, the dishes washed, the clothes laundered, the kids parented, etc.?

LikeLike

Bad Samaritans by Ha Joon Chang has a good chapter on international trade and comparative (and lots of other good chapters on various economic fallacies frequently rolled out in development economics).

Side-point:Ireland’s problems were due to massive over-reliance on construction to fuel the economy which in turn was fueled by massive borrowing at stupid-low rates with unwise tax-incentives. When the property bubble burst many people owed more on their mortgage than the house was worth (in Ireland, you can’t just hand back the keys) and almost all of the high-street banks had to be nationalised, with the EU insisting that their bond debt become national debt.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Alina's Blog.

LikeLike