College metrics of success

There’s a really interesting article over at the Wall Street Journal today, written by Andrea Fuller and entitled The Watchdogs of College Education Rarely Bite. The article discusses the accreditation system for colleges, and how it is more or less dysfunctional. Here’s an example from the article of how they are failing to do a good job:

At Bluefield State College in West Virginia, accreditors from the Higher Learning Commission suggested in 2011 that new electronic signs on campus might be difficult for students to read while driving, according to a copy of the report. The report didn’t mention the college’s graduation rate of 25% or less since 2006.

There is troubling evidence presented in the article that we should definitely pay attention to. It’s quite possible that the accreditors are being paid off, or at least have insufficient reason to come down hard on terribly performing schools. I hope we spend time rethinking the whole system.

However, I think it’s interesting to think about the metrics of success that were used in the article. It’s also an important step towards designing a more “data-driven” accreditation approach.

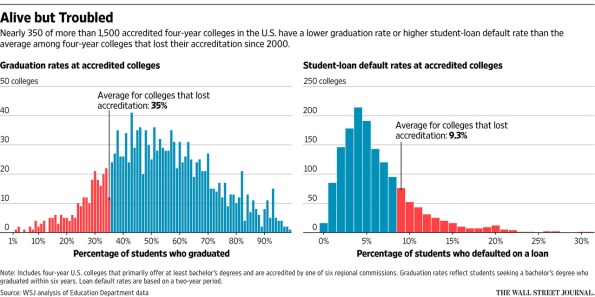

So, for the most part, the article described things in terms of graduation rates and student loan defaults. Not a bad start if you wanted to measure a school: you want high graduate rates, and you want low student loan default rates. Also, they did a good thing, namely compared these numbers to a baseline. In this case their baseline was the average for the schools that have lost accreditation since 2000. Here’s their plot:

Again, these are important metrics, but the logic of the above chart seems to be, if there is a school with a lower graduation rate or a higher default rate than these baseline numbers, or both, then you should also lose your accreditation.

And by the way, I’m not really disagreeing – there are too many bad schools out there, and this seems like a pretty good way of finding truly terrible outliers. Even so, as a data nerd, I need to make the argument that these statistics are highly misleading, or can be.

Say you are trying to compare two school, and one has a higher graduation rate than the other. Do you conclude that the one with a higher graduation rate is better? Well, no. It could just graduate people because it pushes people through the classes without really teaching them anything. Or, the other one could be lower because it takes a chance on more students. In other words, a graduation rate can be lower or higher for good or bad reasons, and taken alone is not a great indicator. Lots of community colleges, moreover, are set up to be transfer schools, and the students deliberately start at that school, then transfer to 4-year colleges, thus lowering the overall graduation rate. It’s a good thing that such schools exist, and we wouldn’t want to close them all down.

Similarly, higher default rates on student loans could be an artifact of a school taking chances on students that otherwise have fewer options, or a bad economy, or even just the type of education that is offered. Engineering schools tend to graduate students who find jobs quickly and easily, but that doesn’t mean every school should become an engineering school. So I wouldn’t compare default rates of two colleges and conclude that the college with a low default rate is necessarily better.

What I’m coming to is that deciding whether a given college has become a failure is actually pretty tricky, and we can complain – and should complain, apparently – about the current system of accreditation, but we can’t claim that it’s as simple as looking at two metrics and deciding what the cut-off is. Choosing a perfect threshold would be tricky.

Or rather, we could do something like that, but then it might have weird effects. If we closed all the schools that don’t keep graduation rates high and default rates low, we might see non-engineering students pushed out of the system, or we might see schools create partnerships with corporations and become federal aid-funded corporate training centers, we might just see (even more) widespread fraud in terms of reporting such things.

I agree that you don’t want every school to be an engineering school just because those schools have low default rates. However, if a high proportion of students from a given institution are defaulting, doesn’t suggest that there’s a disconnect between the cost and the value of the education that those students are getting? And that if the jobs market won’t repay the investment that students are making in their education, then it’s morally incumbent on the schools to charge less for that education?

LikeLike

“it’s morally incumbent on the schools to charge less for that education”: A school doesn’t set its tuition on the basis of moral considerations. It does it on the basis of its financial needs. Unfortunately, the way a college functions financially has changed quite dramatically over the past 50 years, not unlike what has also happened in the corporate world.

LikeLike

The endemic issue with how academia functions is that it’s all of us doing things voluntarily. Also, there is a conflict of interest, since the people who are being accredited might one day serve on the accreditation committee for the institutions of the accreditation committee members. The issues with the system of refereeing journal articles is similar.

This is all breaking down due to new demands and pressures on faculty, and it’s not at all clear, at least to me, how to fix it. Some have suggested, for example, that faculty get paid for these services, but since the payment swill be quite modest (where will the money come from?), this will have negligible impact.

LikeLike

The other problem is merely statistical: there will *always* be some school at the tail end of the distribution. Saying that they need to fall within some percentile range ignores the fundamental nature of distributions. We should indeed look to long tails, but not some percentage of the distribution.

LikeLike

” . . . higher default rates on student loans could be an artifact of a school taking chances on students that otherwise have fewer options, or a bad economy, or even just the type of education that is offered.”

This is a really interesting observation. It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but it’s interesting and important.

LikeLike

From what I can tell, pressure based on graduation rates always winds up producing a corrupt, fraudulent certification institution. Example: NYS high school Regents scores are scaled arbitrarily to graduate a certain number of students. So NYC high schools today can boast a 90% graduation rate, but only 20% of those graduates can pass remedial tests on entering a CUNY community college. And in this case, the effect rolls uphill: now the pressure from the Chancellor of CUNY is to reduce credits (via Pathways), programs, eliminate math requirements (even 8th-grade level algebra), etc. If I could time-travel a century in the future I’m intensely curious as to the end-game of all this: does everyone get a PhD handed to them for continued attendance to age 35? Is there no point when anyone gets certified for real skills/performance?

LikeLike

Universities are financially interested in graduating students because it is a better return on the investment of recruiting them. We recently tried to justify an Ombuds office (crazy that we’re a university of 25K without one); the moral argument was clear, but it was easy to work up a financial argument based on U estimates of how much it ‘cost’ to lose a student. 10-15 students retained a year would pay for the whole affair.

My experience with accreditation is that it is amazingly ineffectual. They want reports, and syllabi, and so many pages of material that it would basically be impossible to review. None of the metrics had to do with impact, or good assessments of student understanding, and almost none had anything to do with students once they leave. Yet universities care a lot about accreditation: if changes were made there, schools would respond. The phrase ‘jump through hoops’ comes to mind.

LikeLike

So…. Standardized testing? I am not a fan, but it begs the question ‘What do you do when nothing is perfect and anything can be done terribly’?

LikeLike

But if the school has both a less than 30% graduation rate and greater than 9% default rate? It’s value should be questioned…

I’m surprised that you don’t recommend looking at both AND making a decision on anticorrelated variables. To some extent that is true of graduation rate and repayment rate. There may be others that are better. It’s clear that graduation rate could be corrected by thr number who enter another accredited school, but why isn’t it. We can all choose variables that aren’t good at evaluating preformance so we should instead choose good ones.

Of course there is the further rule that (like the IRS) any attempt to game the analytics also leads to probation or punishment. Perhaps students should get their money back if a school loses accreditation since they have clearly been harmed and perhaps defrauded.

LikeLike