How do opinions and convictions propagate?

Yesterday I read an interesting paper entitled Social influence and the collective dynamics of opinion formation, written by Mehdi Moussaïd, Juliane E. Kämmer, Pantelis P. Analytis, and Hansjörg Neth, about how opinions and strength of conviction spread in a crowd with many interactions, and how consensus is reached. I found the paper on Twitter through Steven Strogatz’s feed.

The paper

First they worked on individuals, and how they might update their opinion on some topic upon hearing of someone else’s opinion. They chose super unpolitical questions like, “what is the melting point of aluminum?”.

The interesting thing they did was to track both the opinion and the conviction – how sure someone was.

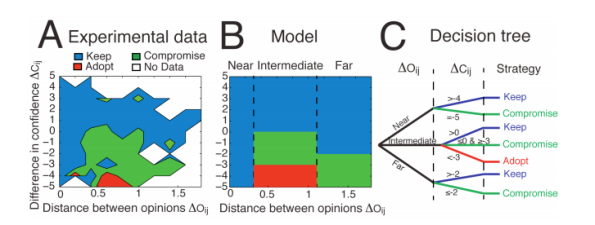

As expected, people did update their opinion if they heard someone else had a somewhat similar opinion, especially if that other person had a stronger conviction. They tended to ignore opinions that were super different, especially if the convictions were weaker. Sometimes they even adopted the other person’s opinion, if it wasn’t too different and if their original conviction was very low. But most of the time they ignored stuff:

What was also interesting, and what we will get back to, is that when they heard other people had similar opinions to their own, their conviction went up without their opinion changing.

Next they used a computer simulation to see how opinions would propagate if no new information was introduced but many interactions occurred, if everyone acted the same in terms of updating opinions, and if they did so time after time.

So what were the results? I’ll explain a couple, please read the paper for more details, it’s short.

The most interesting to me was that, at the end of the day, after many interactions, the convictions of the group always ended up high even if the answer was wrong. This is because, when people heard similar opinions, their convictions rose, but if they heard differing opinions their convictions didn’t lower. But the end result is that, although high conviction correlated with being correct at the start, it had no correlation with being correct by the end.

In fact, conviction correlated to consensus rather than correctness after a few interactions. The takeaway is that, in the presence of not much information, strong convictions might just imply lots of local agreement.

The next result they found was that the dynamical system that was the opinion making soup had two kinds of attractors. Namely, small groups of “experts,” defined as people with very strong convictions but who were not necessarily correct (think Larry Summers), and large groups of people with low convictions but who all happen to agree with each other.

The fact that these two populations are attractors was named by the authors as “the expert effect” and “the majority effect” respectively. And if fewer than 15% of the population were experts, in the presence of a majority, the majority effect dominated.

Finally, the presence of random noise, which correspond to people with random opinions and random conviction levels, weakened both of the above effects. If 70% or more of the population was noise, then the two effects described above vanished.

Thoughts on the paper

- One thing I’ve thought about a lot from working with my Occupy group is how opinions form on a given issue. Since we’re going for informed opinions, we very deliberately start out with a learning phase, which could last a long time depending on the complexity of the subject. We also have a thing against experts, although we do have to trust our sources when we read up on a topic. So it’s kind of balancing act at all times.

- Also, of course, most opinions are not 1-dimensional. I can’t say my opinion on the Fed on a scale between 1 and 100, for example.

- Also, it’s not clear that I update my opinion on issues in exactly the same way each time I hear someone else’s. On the other hand I do continually revise my opinion on stuff.

- The study didn’t look at super political issues. I wonder if it’s different. I guess one of the big differences is in how often someone is truly neutral on a political topic. Maybe you could even define a topic as political in this context somehow, or at least build a test for the politicalness of a topic.

- Let’s assume it also works for political topics. Then the “I heard this so many times it must be true” effect seems to be directly in line with the agenda of Fox News. Also there’s the expert effect going on there as well.

- In any case it’s interesting to note that, if you’re trying to effect opinions, you might either go with “informing and educating the general public” on something or “building up a sufficient squad of experts” on that same thing, where experts are people with super strong opinions and have the ability to interact with lots of people.

You might also like papers from here:

http://www.culturalcognition.net/

They deal with related issues that are quite relevant I believe.

LikeLike

Actually the thought of FOX news was brought to the forefront of my thought when you mentioned “random noise”.

LikeLike

I’d like to see this applied to the “experts” themselves. Confirmation bias is supposed to rise with education, so they’re not immune.

The study assumes that the subjects lack full, accurate information. But in the real world, which accurate information is reliable or meaningful? Is the study’s sample of 59 subjects large enough to qualify, for example, as accurate or meaningful information? I gave a talk recently explaining just how systematically unreliable primary sources are, and how even accuracy and objectivity or the high standard of scholarly method can itself obscure or hide even obvious truths. Stiglitz mentions the shift from GDP to GNP as an economic measure just when globalization became more important. Both are objective measures of an economy, depending on what you value in an economy — production or prosperity. Those are non scientific values. What influences the search for accurate information? Conspiracy theorists (justified or not — I mean no judgment) are highly motivated to seek information.

Occupy also has a consensus, even though its members are reasonably well-informed. Yet the same information in the hands of a Summers or a Richard Epstein would lead to conclusions opposed to Occupy’s bent. A lot depends on commitment — just as important as information, and if Haidt is right, the former precedes the latter. So if information is ambiguous, and seeking it is biased, I’d like to know what influences commitment.

I’ve changed several foundational views over the last few years; trying to figure out how. I just started teaching anthropology — a field of blank-slaters, culture is all — after having taught linguistics (dedicated innationists) for years, with the result that I no longer buy into evolutionary psychology.

Sorry for the length.

LikeLike

You have the shift backwards; it went from GNP to GDP.

LikeLike

Thanks, Larry.

LikeLike

That’s a great point. And keep in mind that experts here are defined as people who have strong conviction, not that they’re right. So if we go with that definition, it would be super interesting to see, if you restrict attention to that subgroup, how they update their opinion, and in particular if they ever do.

LikeLike

This kind of research goes back a few years. I would recommend looking at Dissonance Theory and its research history. And some graph theoretical studies of information transmission in organizations. I’m sorry but I am unable to recall references of this work at this moment.

LikeLike

Ignoring how you try to shape opinion on Larry Summers and Fox, may I suggest a book:”How we know what isn’t so; The fallibility of human reason in everyday life,” Thomas Gilovich. He’s also written a few other books.

LikeLike

Political Epistemics by Andreas Glaeser

is an examination of how people changed their minds during the fall of East Germany. It goes into great detail about how people’s opinions shift (or don’t) when those opinions play an important role in their place in society. It includes a lot of interviews with former Stasi personnel and also a lot of theory about the structure of our understandings of social matters what we have a lot riding on.

I could say something more intelligent if my Kindle program would stop pretending that it can’t access the file for the book. 😦

Most simply and obviously, people will not at all easily accept new ideas (or let go of old ones) when doing so would undermine their faith in the things they need to believe

LikeLike

our understandings of social matters what we have a lot riding on. –>

our understandings of social matters that we have a lot riding on.

LikeLike

Yoi should read this paper:

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11109-010-9112-2

Its about political opinion.

LikeLike