Archive

How math departments hire faculty

I just got back from a stimulating trip to Stony Brook to give the math colloquium there. I had a great time thanks to my gracious host Jason Starr (this guy, not this guy), and besides giving my talk (which I will give again in San Diego at the joint meetings next month) I enjoyed two conversations about the field of math which I think could be turned into data science projects. Maybe Ph.D. theses or something.

First, a system for deciding whether a paper on the arXiv is “good.” I will post about that on another day because it’s actually pretty involved and possible important.

Second is the way people hire in math departments. This conversation will generalize to other departments, some more than others.

So first of all, I want to think about how the hiring process actually works. There are people who look at folders of applicants, say for tenure-track jobs. Since math is a pretty disjointed field, a majority of the folders will only be understood well enough for evaluation purposes by a few people in the department.

So in other words, the department naturally splits into clusters more or less along field lines: there are the number theorists and then there are the algebraic geometers and then there are the low-dimensional topologists, say.

Each group of people reads the folders from the field or fields that they have enough expertise in to understand. Then from among those they choose some they want to go to bat for. It becomes a political battle, where each group tries to convince the other groups that their candidates are more qualified. But of course it’s really hard to know who’s telling the honest truth. There are probably lots of biases in play too, so people could be overstating their cases unconsciously.

Some potential problems with this system:

- if you are applying to a department where nobody is in your field, nobody will read your folder, and nobody will go to bat for you, even if you are really great. An exaggeration but kinda true.

- in order to be convincing that “your guy is the best applicant,” people use things like who the advisor is or which grad school this person went to more than the underlying mathematical content.

- if your department grows over time, this tends to mean that you get bigger clusters rather than more clusters. So if you never had a number theorist, you tend to never get one, even if you get more positions. This is a problem for grad students who want to become number theorists, but that probably isn’t enough to affect the politics of hiring.

So here’s my data science plan: test the above hypotheses. I said them because I think they are probably true, but it would be not be impossible to create the dataset to test them thoroughly and measure the effects.

The easiest and most direct one to test is the third: cluster departments by subject by linking the people with their published or arXiv’ed papers. Watch the department change over time and see how the clusters change and grow versus how it might happen randomly. Easy peasy lemon squeazy if you have lots of data. Start collecting it now!

The first two are harder but could be related to the project of ranking papers. In other words, you have to define “is really great” to do this. It won’t mean you can say with confidence that X should have gotten a job at University Y, but it would mean you could say that if X’s subject isn’t represented in University Y’s clusters, then X’s chances of getting a job there, all other things being equal, is diminished by Z% on average. Something like that.

There are of course good things about the clustering. For example, it’s not that much fun to be the only person representing a field in your department. I’m not actually passing judgment on this fact, and I’m also not suggesting a way to avoid it (if it should be avoided).

Unequal or Unfair: Which Is Worse?

This is a guest post by Alan Honick, a filmmaker whose past work has focused primarily on the interaction between civilization and natural ecosystems, and its consequences to the sustainability of both. Most recently he’s become convinced that fairness is the key factor that underlies sustainability, and has embarked on a quest to understand how our notions of fairness first evolved, and what’s happening to them today. I posted about his work before here. This is crossposted from Pacific Standard.

Inequality is a hot topic these days. Massive disparities in wealth and income have grown to eye-popping proportions, triggering numerous studies, books, and media commentaries that seek to explain the causes of inequality, why it’s growing, and its consequences for society at large.

Inequality triggers anger and frustration on the part of a shrinking middle class that sees the American Dream slipping from its grasp, and increasingly out of the reach of its children. But is it inequality per se that actually sticks in our craw?

There will always be inequality among humans—due to individual differences in ability, ambition, and more often than most would like to admit, luck. In some ways, we celebrate it. We idolize the big winners in life, such as movie and sports stars, successful entrepreneurs, or political leaders. We do, however (though perhaps with unequal ardor) feel badly for the losers—the indigent and unfortunate who have drawn the short straws in the lottery of life.

Thus, we accept that winning and losing are part of life, and concomitantly, some level of inequality.

Perhaps it’s simply the extremes of inequality that have changed our perspective in recent years, and clearly that’s part of the explanation. But I put forward the proposition that something far more fundamental is at work—a force that emerges from much deeper in our evolutionary past.

Take, for example, the recent NFL referee lockout, where incompetent replacement referees were hired to call the games.There was an unrestrained outpouring of venom from outraged fans as blatantly bad calls resulted in undeserved wins and losses. While sports fans are known for the extremity of their passions, they accept winning and losing; victory and defeat are intrinsic to playing a game.

What sparked the fans’ outrage wasn’t inequality—the win or the loss. Rather, the thing they couldn’t swallow—what stuck in their craw—was unfairness.

I offer this story from the KLAS-TV News website. It’s a Las Vegas station, and appropriately, the story is about how the referee lockout affected gamblers. It addresses the most egregiously bad call of the lockout, in a game between the Seattle Seahawks and the Green Bay Packers. From the story:

In a call so controversial the President of the United States weighed in, Las Vegas sports bettors said they lost out on a last minute touchdown call Monday night…

….Chris Barton, visiting Las Vegas from Rhode Island, said he lost $1,200 on the call against Green Bay. He said as a gambler, he can handle losing, “but not like that.”

“I’ve been gambling for 30 years almost, and that’s the worst defeat ever,” he said.

By the way, Obama’s “weigh-in” was through his Twitter feed, which I reproduce here:

“NFL fans on both sides of the aisle hope the refs’ lockout is settled soon. –bo”

When questioned about the president’s reaction, his press secretary, Jay Carney, said Obama thought “there was a real problem with the call,” and said the president expressed frustration at the situation.

I think this example is particularly instructive, simply because money’s involved, and money—the unequal distribution of it—is where we began.

Fairness matters deeply to us. The human sense of fairness can be traced back to the earliest social-living animals. One of its key underlying components is empathy, which began with early mammals. It evolved through processes such as kin selection and reciprocal altruism, which set us on the path toward the complex societies of today.

Fairness—or lack of it—is central to human relationships at every level, from a marriage between two people to disputes involving war and peace among the nations of the world.

I believe fairness is what we need to focus on, not inequality—though I readily acknowledge that high inequality in wealth and income is corrosive to society. Why that is has been eloquently explained by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkerson in their book, The Spirit Level. The point I have been trying to make is that inequality is the symptom; unfairness is the underlying disease.

When dealing with physical disease, it’s important to alleviate suffering by treating painful symptoms, and inequality can certainly be painful to those who suffer at the lower end of the wage scale, or with no job at all. But if we hope for a lasting cure, we need to address the unfairness that causes it.

That said, creating a fairer society is a daunting challenge. Inequality is relatively easy to understand—it’s measurable by straightforward statistics. Fairness is a subtler concept. Our notions of fairness arise from a complex interplay between biology and culture, and after 10,000 years of cultural evolution, it’s often difficult to pick them apart.

Yet many researchers are trying. They are looking into the underlying components of the human sense of fairness from a variety of perspectives, including such disciplines as behavioral genetics, neuroscience, evolutionary and developmental psychology, animal behavior, and experimental economics.

In order to better understand fairness, and communicate their findings to a larger audience, I’ve embarked on a multimedia project to work with these researchers. The goal is to synthesize different perspectives on our sense of fairness, to paint a clearer picture of its origins, its evolution, and its manifestations in the social, economic, and political institutions of today.

The first of these multimedia stories appeared here at Pacific Standard. Called The Evolution of Fairness, it is about archaeologist Brian Hayden. It explores his central life work—a dig in a 5000 year old village in British Columbia, where he uncovered evidence of how inequality may have first evolved in human society.

I found another story on a CNN blog about the bad call in the Seahawks/Packers game. In it, Paul Ryan compares the unfair refereeing to President Obama’s poor handling of the economy. He says, “If you can’t get it right, it’s time to get out.” He goes on to say, “Unlike the Seattle Seahawks last night, we want to deserve this victory.”

We now know how that turned out, though we don’t know if Congressman Ryan considers his own defeat a deserved one.

I’ll close with a personal plea to President Obama. I hope—and believe—that as you are starting your second term, you are far more frustrated with the unfairness in our society than you were with the bad call in the Seahawks/Packers game. It’s arguable that some of the rules—such as those governing campaign finance—have themselves become unfair. In any case, if the rules that govern society are enforced by bad referees, fairness doesn’t stand much of a chance, and as we’ve seen, that can make people pretty angry.

Please, for the sake of fairness, hire some good ones.

Can we put an ass-kicking skeptic in charge of the SEC?

The SEC has proven its dysfunctionality. Instead of being on top of the banks for misconduct, it consistently sets the price for it at below cost. Instead of examining suspicious records to root out Ponzi schemes, it ignores whistleblowers.

I think it’s time to shake up management over there. We need a loudmouth skeptic who is smart enough to sort through the bullshit, brave enough to stand up to bullies, and has a strong enough ego not to get distracted by threats about their future job security.

My personal favorite choice is Neil Barofsky, author of Bailout (which I blogged about here) and former Special Inspector General of TARP. Simon Johnson, Economist at MIT, agrees with me. From Johnson’s New York Times Economix blog:

… Neil Barofsky is the former special inspector general in charge of oversight for the Troubled Asset Relief Program. A career prosecutor, Mr. Barofsky tangled with the Treasury officials in charge of handing out support for big banks while failing to hold the same banks accountable — for example, in their treatment of homeowners. He confronted these powerful interests and their political allies repeatedly and on all the relevant details – both behind closed doors and in his compelling account, published this summer: “Bailout: An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street.”

His book describes in detail a frustration with the timidity and lack of sophistication in law enforcement’s approach to complex frauds. He could instantly remedy that if appointed — Mr. Barofsky is more than capable of standing up to Wall Street in an appropriate manner. He has enjoyed strong bipartisan support in the past and could be confirmed by the Senate (just as he was previously confirmed to his TARP position).

Barofsky isn’t the only person who would kick some ass as the head of the SEC – William Cohan thinks Eliot Spitzer would make a fine choice, and I agree. From his Bloomberg column (h/t Matt Stoller):

The idea that only one of Wall Street’s own can regulate Wall Street is deeply disturbing. If Obama keeps Walter on or appoints Khuzami or Ketchum, we would be better off blowing up the SEC and starting over.

I still believe the best person to lead the SEC at this moment remains former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer. He would fearlessly hold Wall Street accountable for its past sins, as he did when he was New York State attorney general and as he now does as a cable television host. (Disclosure: I am an occasional guest on his show.)

We need an SEC head who can inspire a new generation of investors to believe the capital markets are no longer rigged and that Wall Street cannot just capture every one of its Washington regulators.

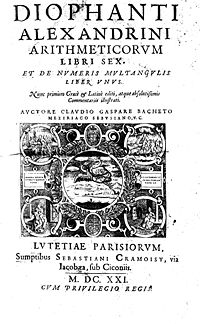

Diophantus and the math arXiv

Last night my 7th-grade son, who is working on a school project about the mathematician Diophantus, walked into the living room with a mopey expression.

He described how Diophantus worked on a series of mathematical texts called Arithmetica, in which he described the solutions to what we now describe as diophantine equations, but which are defined as polynomial equations with strictly integer coefficients, and where the solutions we care about are also restricted to be integers. I care a lot about this stuff because it’s what I studied when I was an academic mathematician, and I still consider this field absolutely beautiful.

What my son was upset about, though, was that of the 13 original books in Arhtimetica, only 6 have survived. He described this as “a way of losing progress“. I concur: Diophantus was brilliant, and there may be things we still haven’t recovered from that text.

But it also struck me that my son would be right to worry about this idea of losing progress even today.

We now have things online and often backed up, so you’d think we might never need to worry about this happening again. Moreover, there’s something called the arXiv where mathematicians and physicists put all or mostly all their papers before they’re published in journals (and many of the papers never make it to journals, but that’s another issue).

My question is, who controls this arXiv? There’s something going on here much like Josh Wills mentioned last week in Rachel Schutt’s class (and which Forbes’s Gil Press responded to already).

Namely, it’s not all that valuable to have one unreviewed, unpublished math paper in your possession. But it’s very valuable indeed to have all the math papers written in the past 10 years.

If we lost access to that collection, as a community, we will have lost progress in a huge way.

Note: I’m not accusing the people who run arXiv of anything weird. I’m sure they’re very cool, and I appreciate their work in keeping up the arXiv. I just want to acknowledge how much power they have, and how strange it is for an entire field to entrust that power to people they don’t know and didn’t elect in a popular vote.

As I understand it (and I could be wrong, please tell me if I am), the arXiv doesn’t allow crawlers to make back-ups of the documents. I think this is a mistake, as it increases the public reliance on this one resource. It’s unrobust in the same way it would be if the U.S. depended entirely on its food supply from a country whose motives are unclear.

Let’s not lose Arithmetica again.

How do we quantitatively foster leadership?

I was really impressed with yesterday’s Tedx Women at Barnard event yesterday, organized by Nathalie Molina, who organizes the Athena Mastermind group I’m in at Barnard. I went to the morning talks to see my friend and co-author Rachel Schutt‘s presentation and then came home to spend the rest of the day with my kids, but they other three I saw were also interesting and food for thought.

Unfortunately the videos won’t be available for a month or so, and I plan to blog again when they are for content, but I wanted to discuss an issue that came up during the Q&A session, namely:

what we choose to quantify and why that matters, especially to women.

This may sound abstract but it isn’t. Here’s what I mean. The talks were centered around the following 10 themes:

- Inspiration: Motivate, and nurture talented people and build collaborative teams

- Advocacy: Speak up for yourself and on behalf of others

- Communication: Listen actively; speak persuasively and with authority

- Vision: Develop strategies, make decisions and act with purpose

- Leverage: Optimize your networks, technology, and financing to meet strategic goals; engage mentors and sponsors

- Entrepreneurial Spirit: Be innovative, imaginative, persistent, and open to change

- Ambition: Own your power, expertise and value

- Courage: Experiment and take bold, strategic risks

- Negotiation: Bridge differences and find solutions that work effectively for all parties

- Resilience: Bounce back and learn from adversity and failure

The speakers were extraordinary and embodied their themes brilliantly. So Rachel spoke about advocating for humanity through working with data, and this amazing woman named Christa Bell spoke about inspiration, and so on. Again, the actual content is for another time, but you get the point.

A high school teacher was there with five of her female students. She spoke eloquently of how important and inspiring it was that these girls saw these talk. She explained that, at their small-town school, there’s intense pressure to do well on standardized tests and other quantifiable measures of success, but that there’s essentially no time in their normal day to focus on developing the above attributes.

Ironic, considering that you don’t get to be a “success” without ambition and courage, communication and vision, or really any of the themes.

In other words, we have these latent properties that we really care about and are essential to someone’s success, but we don’t know how to measure them so we instead measure stuff that’s easy to measure, and reward people based on those scores.

By the way, I’m not saying we don’t also need to be good at content, and tasks, which are easier to measure. I’m just saying that, by focusing on content and tasks, and rewarding people good at that, we’re not developing people to be more courageous, or more resilient, or especially be better advocates of others.

And that’s where the women part comes in. Women, especially young women, are sensitive to the expectations of the culture. If they are getting scored on X, they tend to focus on getting good at X. That’s not a bad thing, because they usually get really good at X, but we have to understand the consequences of it. We have to choose our X’s well.

I’d love to see a system evolve wherein young women (and men) are trained to be resilient and are rewarded for that just as they’re trained to do well on the SAT’s and rewarded for that. How do you train people to be courageous? I’m sure it can be done. How crazy would it be to see a world where advocating for others is directly encouraged?

Let’s try to do this, and hell let’s quantify it too, since that desire, to quantify everything, is not going away. Instead of giving up because important things are hard to quantify, let’s just figure out a way to quantify them. After all, people didn’t think their musical tastes could be quantified 15 years ago but now there’s Pandora.

Update: Ok to quantify this, but the resulting data should not be sold or publicly available. I don’t want our sons’ and daughters’ “resilience scores” to be part of their online personas for everyone to see.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is overwhelmed with joy today, readers, and not only because she gets to refer to herself in the third person.

The number and quality of math book suggestions from last week have impressed Auntie dearly, and with the permission of mathbabe, which wasn’t hard to get, she established a new page with the list of books, just in time for the holiday season. I welcome more suggestions as well as reviews.

On to some questions. As usual, I’ll have the question submission form at the end. Please put your questions to Aunt Pythia, that’s what she’s here for!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I was one of those kids who when asked “What do you want to be when you grow up?” said “Errrghm …” or maybe just ignored the question. Today I am still that confused toddler. I have changed fields a few times (going through a major makeover right now), never knew what I want to dive into, found too many things too interesting. I worry that half a life from now, I will have done lots and nothing. I crave having a passion, one goal – something to keep trying to get better at. What advice do you have for the likes of me?

Forever Yawning or Wandering Globetrotter

Dear FYoWG,

I can relate. I am constantly yearning to have enough time to master all sorts of skills that I just know would make me feel fulfilled and satisfied, only to turn around and discover yet more things I’d love to devote myself to. What ever happened to me learning to flatpick the guitar? Why haven’t I become a production Scala programmer?

It’s enough to get you down, all these unrealized hopes and visions. But don’t let it! Remember that the people who only ever want one thing in life are generally pretty bored and pretty boring. And also remember that it’s better to find too many things too interesting than it is to find nothing interesting.

And also, I advise you to look back on the stuff you have gotten done, and first of all give yourself credit for those things, and second of all think about what made them succeed: probably something like the fact that you did it gradually but consistently, you genuinely liked doing it and learning from it, and you had the resources and environment for it to work.

Next time you want to take on a new project, ask yourself if all of those elements are there, and then ask yourself what you’d be dropping if you took it on. You don’t have to have definitive answers to these questions, but even having some idea will help you decide how realistic it is, and will also make you feel more like it’s a decision rather than just another thing you won’t feel successful at.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

My boss lacks leadership qualities and is untrustworthy, and I will resign soon. Should I tell his boss what I think of this boss?

Novembertwentyeleven

Dear November,

In Aunt Pythia’s humble opinion, one of the great joys of life is the exit interview. Why go out with a whimper when you have the opportunity to go out with a big-ass ball of flame?

Let’s face it, it’s a blast to vent honestly and thoroughly on your way out the door, and moreover it’s expected. Why else would you be leaving? Because of some goddamn idiot, that’s why! Why not say who?

You’ll hear people say not to “burn bridges”. That’s boooooooring. I say, burn those motherfuckers to the ground!

Especially when you’re talking about people with whom you’d never ever work again, ever ever. Sometimes you just know it’ll never happen. And it feels great, trust me. I’m a pro.

That said, don’t expect anyone to listen to you, cuz that aint gonna happen. Nobody listens to people when they leave. Sadly, most people also don’t listen to people when they stay, either, so you’re shit out of luck in any case. But as long as you know that you’re good.

I hope that helped!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How should I organize my bookshelf? I have 1000+ books.

Booknerd

Readers! I want some suggestions, and please make them nerdy and/or funny! I know I can count on you.

——

Please ask Aunt Pythia a question! She loves her job and can’t wait to give you unreasonable, useless, and possibly damaging counsel!